In the spring of 2010, mass protests by the National United Front of Democracy Against Dictatorship, also known as the 'Red Shirts', took over central Bangkok for two months. Their occupation only ended with a military crackdown on May 19, with more than 80 civilians and six soldiers dead, and 2,100 injured. Disentangling truth and lies proved a challenge for journalists on the ground.

May 18, 2010, Bangkok. Thailand, having experienced 15 coups since the Siamese Revolution of 1932, which transformed the kingdom from an absolute to a constitutional monarchy, is no stranger to political unrest. But recent events in the capital Bangkok have threatened to condemn the nation to civil war.

While hundreds of journalists from across the world have converged on the city to report on every nuance in the class-fuelled conflict, they have been joined by many more “citizen journalists” using social media to tweet, text and blog every development and their own opinions. But how accurate are such reports and should we trust this new species of reportage?

ONE MONTH EARLIER, early on the evening of Thursday, April 22, and Silom Road in the steamy Thai capital appeared relatively untroubled for a major downtown shopping area in a city under siege.

Office workers stepped into the street to bypass razor wire that the army had stretched in rolls across pavements. But they were stopping off, as usual, at the end of another working day to buy papaya salad and fish-ball noodle soup from busy roadside vendors before taking the Skytrain home.

Grinning tourists in garish shorts and singlets posed for photographs with heavily armed Thai soldiers, sweating profusely but seemingly relaxed under head-to-toe riot gear.

With their flak jackets hanging loose and protective matt-black helmets buckled to their belts, war correspondents — perhaps weaned on the hardships of Baghdad or Helmand province — strolled by, ice-creams in hand, in the last of the day’s sunshine.

Some kicked back on the patio of O’Reilly’s Irish pub with a pint and a cigarette.

From the eastern end of Silom Road, however, at Sala Daeng intersection, fiery speeches could be heard emanating from loudspeakers at the corner of Lumphini Park. The junction was the southern-most and most determinedly defended limit of the “Red Shirt” encampment that, occupied by up to 20,000 anti-government protesters, had paralysed more than a square mile of central Bangkok’s prime commercial district for weeks.

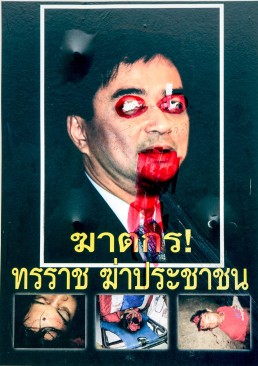

In the days before April 22, the Reds — largely working-class supporters of Thailand’s ousted leader Thaksin Shinawatra, the billionaire former telecoms magnate who, they say, gave the poor a voice, and who insist current Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva’s government took power illegitimately, backed by the army and the judiciary — had fortified their side of the junction with banks of old tyres, thousands of sharpened bamboo staves, petrol canisters, protective netting and piles of smashed paving stones to be used as missiles.

The current government, the Reds claim, represents an elite unsympathetic to their problems. Journalists, along with the simply curious, were allowed access to the camp. Inside, women napped under the shade of Lumphini’s trees as tattooed youths produced homemade rockets nearby. Small children played; Buddhist monks in saffron robes carried spears.

By the end of the day, the scene had turned ugly. Although the Reds appeared not to have broken their lines in an attempt to storm Silom as threatened, a rival demonstration of 1,000 “No Colours”, insisting their city be returned to normality, had begun nearby.

The No Colours waved posters of the country’s revered King Bhumibol Adulyadej and demanded that the Reds — many having travelled to the capital from the country’s largely rural northeast to make their voices heard — “Go home! Go home! Go home!”

Four — or was it five? — explosions rang out that evening and blood pooled at the entrance to a branch of the Bank of Ayudhya, exactly where the No Colours had staged their noisy opposition to the Reds. The bank’s plate-glass window had been shattered and, next to the coagulating puddle, a small national flag had been crossed over neatly with the yellow flag of the king, suggesting cooperation.

With young Thai soldiers, many visibly shaking behind riot shields, standing shoulder to shoulder at intervals along a darkened and now empty Silom Road, foreign correspondents, photographers and cameramen milled and chatted outside McDonald’s, but all was now quiet.

In the previous hours my mobile phone had regularly beeped with incoming messages from friends in Hong Kong, Bangkok and Shanghai. “THREE DEAD – GRENADES”, read one text. Another: “SHOOTINGS ON SILOM”. Another: “You okay? Two foreigners killed in Bangkok”.

THE FOLLOWING DAY the Bangkok Post newspaper led with the headline “BOMB TERROR GRIPS SILOM”. The story stated: “Silom was turned into a war zone Thursday night after four grenades were fired into the area where anti-Red Shirt protesters had converged, killing three people and injuring 75.”

This information, the Post reported, had come before midnight on April 22, directly from Deputy Prime Minister Suthep Thaugsuban.

Like the text messages I had received, the Post’s initial report proved inaccurate: only one person, a 26-year-old Thai woman, had been killed that evening and the newspaper revised its death toll with an online post at 11.08am the next day.

Channel NewsAsia, The Sydney Morning Herald, Al Jazeera, Voice of America and many other news outlets had also reported Suthep’s claim that three had been killed, as well as his statement that an M79 grenade launcher had been used in the attacks. “It was clear that it was shot from behind the King Rama VI Monument [at the southwestern entrance to Lumphini] where the Red Shirts are rallying,” he had told reporters.

What turned out to be inaccurate information had come from a senior Thai government official, thereby highlighting the difficulties journalists — and their readers — have had in wading through and making sense of what British author and journalist Andrew Marshall, a frequent contributor to Time magazine and a Bangkok resident of 15 years, has called “the tsunami of bullshit and obfuscation from all sides”.

HALF-TRUTHS, UNSUBSTANTIATED rumour and blatant bias have accompanied the gathering of the fluid and fast-moving news in Bangkok, centre of the worst political violence in the Land of Smiles’ modern history. April 22 was not the first, or bloodiest, clash since the National United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD), the political pressure group supported by the Red Shirt protesters, marched on the capital in mid-March.

Nor did it result in the most blatant case of distortion, deliberate or not, landing in the hands of the press.

On April 10, troops tried without success to take back control of a UDD protest site at Phan Fah Bridge, near Khao San Road, a popular hangout for international backpackers passing through Bangkok.

Twenty-five people perished in clashes, including Hiro Muramoto, a 43-year-old Japanese cameraman for Reuters, who died from a gunshot wound to the chest.

“There were no live bullets fired at protesters,” government spokesman Panitan Wattanayagorn promptly announced on Thai television, insisting that only tear gas and rubber bullets had been used by the army.

French television news channel France 24 quickly released footage showing soldiers firing live rounds, however, and the government backtracked, Abhisit admitting in a televised statement that such ammunition had been employed by soldiers — but only in “self defence”.

“Video footage showed troops firing live rounds straight ahead … it’s clear bullets shot at high velocity killed many. Many believe protesters were killed by soldiers”

Jason Szep, Thailand bureau chief, Reuters

Reuters continues to press for the results of an inquiry into Muramoto’s killing, believing the government has information that could provide answers for his grieving family.

“The use of ‘self defence’ is vague and arguably misleading,” says Jason Szep, bureau chief of Thailand and Indochina for Reuters News and TV. “Video footage showed troops firing live rounds straight ahead, though the footage itself did not show the rounds going into the crowd. But it’s clear bullets shot at high velocity killed many. Many believe protesters were killed by soldiers.”

Marshall is less diplomatic, and pessimistic regarding the search for truth in the matter. “The government’s delay in admitting that soldiers had killed civilians was stupid and self-defeating,” he says. “The Reds constantly predicted crackdowns, which never happened but perhaps that was more an indication of their (justifiable) paranoia than any deliberate attempt to deceive. The truth of such events as April 10 will probably never be known.”

SINCE APRIL 22 AND the explosions on Silom Road, the Red encampment’s barricades have grown higher and thicker to resemble medieval fortifications. The Reds have procured kilometres of razor wire and the bamboo wall is festooned with rags to be soaked in petrol and lit should the military mount what is widely considered the inevitable attack on the camp. Every day the crisis has deepened.

On April 23, a UDD proposal to hold elections in three months was rejected by Abhisit. On April 28, security forces and Reds clashed on the outskirts of Bangkok and a soldier was killed.

On April 30, more than 200 Reds forced their way into Chulalongkorn Hospital, near the Sala Daeng intersection. They were searching for army snipers and soldiers, but found none and hospital staff promptly moved about 600 patients to other buildings and hospitals.

On May 3, Abhisit presented a reconciliatory roadmap that included elections for November 14. Although tentatively accepted by the protesters, Abhisit dropped the offer after the Reds made more demands, most notably for those responsible for recent Red deaths to be brought to justice.

In their accounts of these developments and others, both sides have frequently employed spin and bias.

On May 6, the government-run National News Bureau Public Relations Department released an article under the headline “4 PATIENTS DIED FROM CHULALONGKORN HOSPITAL EVACUATION”. Deep in the text, however, the story mentioned that public health minister Jurin Laksanavisit “reported that three transferred patients had died from cancer and another died from obesity, heart disease and renal failure”, prompting blogger Bangkok Pundit to ask, “So the Reds gave them cancer?”

While anti-Thaksin, pro-establishment “Yellow Shirt” protesters — a loose grouping of royalists, the urban elite and professional middle classes — have been noticeable by their absence in recent months, the appearance of the No Colours (Reds suspect they are mostly Yellow) has been only the start of additional confusion as the crisis has divided society and caused rifts in the armed forces.

The term “watermelon soldier”, for instance, is now used to describe someone who wears green on the outside but is red inside. A “pineapple soldier” is considered yellow at heart.

“Tomato” has been used for the police, many of whom hail from rural areas and are assumed to be Red to the core. Rumours circulate of a disbanded group of specialist military rangers operating in the shadows.

The Reds’ frontline security forces usually wear black and were said to be operating under the leadership of Major General Khattiya Sawasdipol, a rogue army officer more commonly known as Seh Daeng, or the “Red Commander”.

She Daeng was shot in the head, apparently by a sniper, at Sala Daeng on May 13, as he was being interviewed by a New York Times reporter. An early CNN report noted that he had been shot in the chest; another that he was not in critical condition. He died from kidney failure on May 17.

And while their detractors assert that the Reds are pawns of Thaksin, and that many are simply thugs allegedly being paid Bt500 (about US$15 at the time) a day to protest, many ask whether the movement has outgrown its mentor in exile. “The government wants Thaksin to be the chief funder and inspiration for the Reds so that it can claim these are paid hoodlums fighting one man’s battle,” says Marshall. “But many Reds have real grievances. The government, and the Yellows, need to pay more than just lip service to this.”

Szep of Reuters is more circumspect in his appraisal. “It’s a very disparate movement,” he says. “On some level it certainly has moved beyond Thaksin. And they are very deliberately trying to play down their Thaksin links. But in the northern provinces he remains a powerful symbol for the Red Shirts and that doesn’t seem to be changing.”

One foreign correspondent for a European news agency, a Southeast Asia resident of almost a decade who wishes to remain anonymous, goes further: “Definitely, their movement has awakened a sense of political entitlement among the rural and urban poor, and that will not go away. And they seem to be forging an identity quite separate to Thaksin, who has taken a back seat in recent weeks.

“Also, the Reds have gone some way to boosting their credibility among the media, both Thai and foreign, despite initial scepticism that they are the paid foot soldiers of Thaksin and his allies. Their strong communications have helped — they are easily contactable by phone or in person at the camp and they continue to stream their regular press conferences over the internet, despite constant efforts to block the hosting sites.”

NOBODY COVERING THE Bangkok standoff claims the Reds are whiter than white. “One big lie is the Reds’ insistence they are a non-violent movement,” says Marshall. “I don’t think they really understand the concept. The non-violence of [Martin Luther] King and Gandhi wasn’t, ‘I’m peaceful until you hurt me, and then I’m allowed to hurt you back.’ It was non-violence, period.”

A stroll around the Red camp proves the journalist’s point. Centred on Ratchaprasong intersection, home to luxury hotels and designer-brand shopping malls and a retail playground for the city’s affluent, the area was deliberately chosen for the UDD’s city-within-a-city to inflict most disruption: the crisis has devastated tourism and slowed investment and growth in Southeast Asia’s second-largest economy.

At Ratchaprasong, protesters gather in numbers every evening to listen to speeches made by UDD leaders from a stage dominated by banners reading, “Welcome to Thailand – We Just Want Democracy” and “Peaceful Protestors Not Terrorists”. Under huge and now incongruous mall advertisements for the like of Loewe, Gucci and Celine, protesters wave placards reading “Non-Violence” and “Peace in Thailand”, as well as noisy foot-shaped clappers.

Heading down Ratchadamri Road and towards Sala Daeng, the sheer size of the camp can be appreciated — and how it has come to cater to its roughing-it inhabitants’ diverse needs.

Stalls sell everything from Red T-shirts (Bt50-100) to red curries and rice (Bt30). There are mobile-phone charging stations, makeshift canteens and children’s book stalls. A VCD titled Who Is The Real Killer?, with English subtitles, that analyses the events of April 10 from a Red perspective is handed out free.

Popular and practical souvenirs of the troubles include flip-flops featuring Abhisit’s face (Bt50); Buddhist Thais consider the soles of the feet the lowest and dirtiest part of the body, which is why A4 posters of the prime minister have also been pasted onto pavements where the crowds are thickest.

On three occasions I am approached while in the camp, in each case by Thai women claiming to be Bangkok residents. Seeing my camera, they enquire whether I am a reporter and ask that I “tell the truth” about them in any report. “Please tell the world we are not violent,” they say. “We are peaceful people.”

A few metres away, stalls openly sell hastily machined wooden catapults for Bt30 and bags of marbles or metal nuts (10 for Bt10) to fire from those catapults. More professional-looking slingshots, with greater power and accuracy, can be picked up for Bt100–200.

“Some foreign journalists initially wore press scarves from the Red Shirts, unaware that some of the Thai words on them were Red Shirt political slogans, destroying the journalists’ neutrality in other Thais’ eyes”

BBC correspondent Vaudine England

Following the clashes of April 10, the army claimed to have lost nine M16 rifles, 25 Tavor rifles, six anti-aircraft guns, 116 shields, 105 batons and 80 body-armour suits. Ammunition supposedly missing includes 580 rubber-bullet rounds, 600 anti-aircraft rounds and 8,182 M16 rifle rounds. Many have been recovered; others have not.

The Reds have not been averse to attempting to hoodwink the media.

“In this dispute, where many aspects of life have become politicised, we have to work on staying neutral,” says BBC correspondent Vaudine England. “Some foreign journalists initially wore press scarves from the Red Shirts, unaware that some of the Thai words on them were Red Shirt political slogans, destroying the journalists’ neutrality in other Thais’ eyes.”

The news-agency correspondent confirms: “We were told we had to go to the Reds’ camp to be issued with new media armbands. We got the impression we wouldn’t be allowed in if we only had the existing band issued by the Thai Journalists Association.

“So someone went to the camp, brought back a stack of these new green plastic bands and asked one of our Thai staff the meaning of the wording on them. It turned out to be ‘dissolve parliament’. They were quite surprised when we called and said we had no intention of wearing their propaganda.”

WHILE TRADITIONAL MEDIA have generally coped admirably, swiftly and accurately in the face of so much information and disinformation (Reuters, for instance, invested in a team of 40 editorial staff in Thailand), new media like Twitter have come into their own during recent events in Bangkok.

One keen follower was Australian Jason Gagliardi, creative director at a Bangkok advertising agency and a former journalist whose work has featured in Time and the UK’s Sunday Telegraph.

“I do think Twitter has become a game-changer in how people follow the news,” Gagliardi says. “You have to filter out the wheat from the chaff, but if you follow enough of the right people you can build up a very good picture of how events are unfolding.

“I found some of The Nation [newspaper] and Bangkok Post journalists to be good sources: @tulsathit and @Veen_NT at The Nation and @Terryfrd from the Post, with lots of real-time translations of Red speeches and posturing. I follow Andrew Marshall (@journotopia) and he was posting great stuff on the April 10 debacle.

“An Aussie guy, John le Fevre (@Photo_Journ), has been on the ground tweeting non-stop since the start of the thing. And I also follow some very pro-Yellow Bangkok rich kids who tweet vociferously for a crackdown. There are many others.

“The beauty of Twitter, and also perhaps its real danger, is that you only build up the picture of what’s going on from whom you choose to follow. So if you only follow people who support your bias or causes, you will get a very one-sided picture. But if you follow all sorts of people, especially some reliable journalists, it’s an excellent real-time source.

“I have been glued to it: the updates, the debate … By the time you go online to read a newspaper it often feels like old news.”

Marshall, it transpires, was not tweeting professionally. “I didn’t report for Time on the Red Shirts. I tweeted it, really as an experiment, and was surprised at how my follower count jumped from 150 to over 1,000,” he says, adding that he only trusted what he actually saw, and has found it hard to believe any “facts” coming from Reds, Yellows, government, politicians, police or military.

“There was a great hunger for instant updates on the situation, especially with so many tourists coming to Thailand and with the violence occurring so close to tourist areas such as Khao San … It turns out there are some very reliable citizen reporters out there.”

Many working in more traditional media, however, maintain their distance from the phenomenon.

“The Thai crisis is a good example of a story where Twitter, SMS alerts from local newspapers and so on are great tools for journalists, but have to be treated extremely cautiously,” says the European news agency correspondent. “Thai politics is very grey; there are so many false alarms, misinterpretations and inaccuracies, as well as much gossip swirling around. Most reputable news organisations only report a fraction of what they hear. The main task is sifting.

“For example, there are several layers of Red leadership. When one leader makes a strong statement, how much weight should you give it? Is it likely to be moderated or contradicted by a more senior leader later that day? Is it really the position of the movement as a whole or is it a throwaway comment?”

Szep largely agrees, though he has reservations about the accuracy of texts from local reporters.

“I recall one week when nearly every morning local media were sending out SMS messages saying a crackdown was imminent and soldiers were about to advance on the protesters in the main shopping district at such-and-such a time,” Szep says. “It never happened. There are loads of rumours flying around all the time.”

Australian freelance photographer Jack Picone is more damning. Having worked in numerous war zones delivering images for the likes of Newsweek, Stern and The Independent, Picone argues that citizen journalism, in addition to being frequently inaccurate, could prove dangerous in conflicts for those on the ground.

“Often in war zones there is sound intelligence [with which] to make informed decisions about what your next move will be, but in situations like April 10, chaos and confusion add another layer of danger,” Picone says. “Further confusion was added via citizen journalism, with the public filing via social media like Twitter hopelessly inaccurate accounts of what was happening — and in several cases things that did not happen at all.

“As much as citizen journalism is now sexy and in vogue, it is quite disturbing how definitively wrong the untrained public can be in these situations.”

NO JOURNALIST APPROACHED for this article could predict with any confidence what lay ahead for the Reds, the government or for Thailand. By the time you read these words Bangkok may be in flames and the country facing civil war; the army may have attacked the camp, with heavy losses on both sides; or the Reds may have dispersed.

By the end of May 14, the shooting of Red-affiliated rogue army officer Khattiya, coupled with a more aggressive approach to Red protesters from the army, had resulted in an escalation of violence.

May 15 to 18 saw clashes breaking out at locations across the Thai capital. With the death toll rising by the hour, the UK’s Times newspaper stated on May 15: “Bangkokians got on with what Bangkokians do best: spreading rumours. The mobile-phone operators had a field day as misinformation, make-believe and wishful thinking were furiously texted as facts.”

By midnight on May 17, Thai government figures — clearly not always the most accurate — estimated the total number of deaths since the standoff began in March at 65, with more than 1,700 wounded.

The recent injured include a photographer for The Nation, and freelance Canadian journalist Nelson Rand, 34, who took three bullets while, coincidentally, on assignment for the France 24 television channel, which had uncovered the government’s lie about troops shooting live rounds at Phan Fah Bridge. Rand is out of danger.

It is frequently said that “the first casualty of war is the truth” and that has proved correct in this confrontation. Ironically, as new media have become more prevalent, transforming themselves into a source of information for journalists and the public, and forcing traditional news gatherers to react at increasing speed, the state of affairs, rather than becoming clearer, has on countless occasions turned murkier. ◉

POSTSCRIPT

May 20, 2010. The Guardian newspaper reports that after a bloody “final crackdown” the Red Shirts” camp has been obliterated and the Reds’ leaders arrested. The violence has left at least 83 people dead and 1,800 injured, mostly civilians.

On May 19, troops marched into Lumphini Park and armoured personnel carriers advanced through streets. Some protesters, in a last-ditch show of rage, turned their anger on the media.

“Shops were looted, buildings set [ablaze] and journalists attacked, the Guardian reports. “The Channel 3 news station was set on fire and staff on the city’s English-language papers, The Nation and the Bangkok Post, were evacuated after threats.”

Italian freelance photographer Fabio Polenghi, 48, was shot dead by troops as the protest camp was overrun. ◉

A version of this story ran in Asia Literary Review in 2010. Download PDF.

SHARE