Foot binding may seem abhorrent today, but the resulting deformity once conveyed privilege and status in China. Some of the last surviving women to have undergone the crippling process explain the reasons why — and recall the excruciating pain.

BUNDLED UP AGAINST the morning chill in a man’s voluminous jacket and knitted woollen hat, Yang Zhaoshi perches on a rattan chair in the courtyard of her family’s ramshackle ancestral home.

Hunched and increasingly deaf with her advanced years, she leans forward unsteadily to hear a question that is never easy to ask of a lady. “I can’t really remember how old I am,” Yang answers slowly. “But I know I was born in the year of the ox.”

“Mother will be 100 in a week or two, I think,” says Yang’s ruddy, weather-beaten eldest son, who is a none-to-sprightly 83 himself. It is not Yang’s longevity that is surprising, however. What makes the nonagenarian especially unusual are her tiny feet, which measure just over 10cm in length.

Yang is one of the few remaining women left in China to have undergone foot binding.

YANG’S MOTHER BEGAN tightly binding her feet with strips of cloth when she was six years old, forcibly folding the youngster’s four smallest toes under the soles and deliberately breaking delicate bones to mould each foot into the shape of a so-called “golden lotus”, revered for centuries in China as the epitome of feminine beauty, refinement, even sexual attractiveness.

Further squeezed and sculpted by hand to create a high arch and a hoof-like appearance, Yang’s shattered feet would set that way and remain deformed for life.

“It was so painful, but my mother said that if I didn’t do it I would never find a husband, nobody would have me,” says the widowed mother of four, and grandmother, great-grandmother and great-great-grandmother of more descendants than she can immediately recall.

Yang is matriarch of five generations of her clan residing in Liuyi, a nondescript, agriculture-driven village of 2,000 or so people in south-western China’s Yunnan province.

“It wasn’t a strange thing to do in those days — many girls in Liuyi had small feet. The tradition was strong here. If your feet were small, you were admired, you were special.”

THE FOOT-BINDING PROCESS began when a girl was between four and seven years old. Firstly, her feet were soaked in warm water or animal blood mixed with herbs. With her toenails clipped short, she was given a soothing foot massage.

Then the horror would begin — every toe would be broken except for the big toe. Then the foot was wrapped with binding cloth. Every day, the foot would be unwrapped and wrapped again, but tighter. The youngster’s feet would be squeezed into smaller and smaller shoes until the foot was between 7cm and 10cm long.

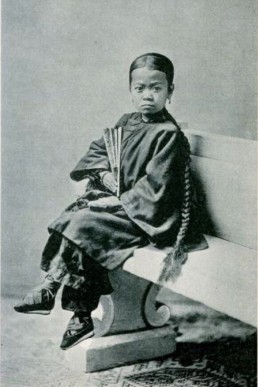

Though legend says the practice began thousands of years ago, written evidence suggests it likely was adopted in earnest much later, at the court of the Song dynasty (960–1279AD). Scholars agree that binding was a sign of social status — if a woman’s feet were bound, and therefore she was unable to perform manual labour, she would be viewed as of the noble class.

Others insist foot binding was a form of female subjugation, and that it gradually became a sexual fetish for Chinese males. What is known is that foot binding slowly spread to the lower classes aspiring for higher social status.

“It would hurt so much, but others would laugh if you couldn’t manage it, so I forced myself”

Yang Zhaoshi, aged 99

There is no conclusive historical evidence for when the custom began in Yunnan or in China as a whole, says Dorothy Ko, a professor of history at Columbia University’s affiliated Barnard College in New York, and author of the book Cinderella’s Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding.

“One may say the ideal of dainty feet was concocted by male poets in the Tang dynasty [618–907AD], and taken up as an actual practice by women in elite families by the 12th and 13th centuries,” says Ko.

“The missing step — one that I can only conjecture — is that when the Tang court fell in 907, palace dancers were dispersed to courtesan houses in the south, introducing a mild form of binding — like a ballerina’s pointes.”

Yang says that, though mothers or other female relatives traditionally initiated the daily foot-binding process, young girls were expected to take over the agonising, crippling ritual within weeks.

“It would hurt so much, but others would laugh if you couldn’t manage it, so I forced myself,” Yang says. Today, however, she requires a helping hand with her feet. “I’m old now and it isn’t easy to bend, so my second-son’s wife does it,” she adds, nodding towards her 70-something daughter-in-law.

“It only takes a minute,” the woman offers, stepping forward, crouching at Yang’s side and smiling broadly. “Would you like to see?”

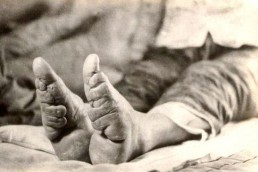

Without waiting for an answer, she snatches Yang’s right leg, crosses it over the older woman’s left leg and removes her black felt shoe, which is ornately embroidered with colourful flowers and songbirds. She whips off Yang’s sock and deftly unwraps the faded blue-canvas binding, quickly revealing the gnarled, scaly and slightly pungent foot beneath.

Yang’s smallest toes have been crushed almost flat, and a shockingly deep cleft — the result of unnaturally forcing the arch upward, thereby reducing the foot’s length — runs between the heel and the ball of Yang’s foot.

Yang Zhaoshi's daughter-in-law unwraps her bound foot. Photos: Gary Jones

YANG WAS BORN JUST one year after foot binding was banned in China, in 1912, following the fall of the imperial Qing dynasty and the establishment of the republic. The practice, seen by the new Nationalist regime as backward and shameful, continued furtively in remote areas, however.

Largely isolated from the authorities, the area around Liuyi was one of the last places in China to abandon the ritual, and girls’ feet were still being bound as late as the early 1950s — even after the communists had come to power in 1949 and Mao Zedong had famously extolled gender equality by declaring that women “hold up half the sky”.

By the late 1990s, in fact, there were still more than 200 bound-feet women living in and around Liuyi. Today, there are fewer than 20.

“The mountains are high and the emperor is far away,” says Yang’s eldest, employing an ancient Chinese saying to explain how foot binding persisted even once banned. Dressed in a blue Mao jacket and cloth cap, he looks every bit as out-of-time — in a modern China of cloud-busting skyscrapers, super-fast bullet trains and glitzy shopping malls — as his mother.

“[Foot binding] was kept secret,” he says. “If government officials came, the village girls would be locked away. Once the officials had gone, life would carry on as normal.”

A short stroll from Yang’s home, Pu Guifeng is exchanging village gossip at a shop selling seeds and fertiliser. Though the 77-year-old is willing to chat, she waves away the camera like a seasoned movie star dealing with bothersome paparazzi. “No photos,” Pu barks, grinning.

Pu has enjoyed a certain level of fame. In the early 1990s, she and an energetic sorority of Liuyi’s other remaining women with bound feet formed an unlikely dance troupe, performing as far away as the provincial capital Kunming, a three-hour drive to the north.

“We danced some disco, we did traditional tai-chi moves with fans and scarves,” says Pu. “We were very popular; quite famous, in fact. Even recently, just two weeks ago, some television people came down from Beijing, wanting us to dance for them.”

Pu says that, though many view her as an oddity nowadays, once upon a time the opposite was true. “Back then, if you didn’t have small feet,” Pu says, “you would be shamed for being different — you didn’t fit in, you were considered weird.”

And though the dance troupe was at best a novelty, and at worst something of a modern-day freak show, she relished her brief moment in the spotlight. “It’s a shame we don’t dance anymore,” Pu says. “I’m still quite nimble, but some of the troupe are too old now; in their 90s. It’s difficult to get them into a car to travel long distances.”

A TWO-HOUR DRIVE south of Liuyi, heading towards the border with Vietnam, the picturesque and pleasingly well-preserved walled hamlet of Tuanshan nestles on low hill amidst verdant farmland.

Originally established as a mining centre in the 14th century, Tuanshan’s ochre-hued residences, temples and ancestral halls were constructed later — during the 19th and early 20th centuries — when the area prospered from trade with Southeast Asia made possible by a French-built railway.

Outside one ancestral hall, an elderly woman without bound feet squats on the grey-stone threshold. A cardboard box at her side contains exaggeratedly miniscule silk shoes that she sells for Rmb20 (then about US$3) a pair to the occasional tourist.

“The small feet women used to make them and sell them, but they are too old now,” she says, adding that there are only two such women remaining in Tuanshan. “Head down towards the lake. Ask for Madam Zhu.”

Zhu Shao Qiong is soon found wiling away the sunny afternoon in the small convenience store owned by her third son (she has four, and three daughters). She is elegantly decked out in a traditional blue smock, pressed grey-blue trousers and peach socks, and her feet are encased in dainty black-leather lace-up shoes not much longer than a cigarette lighter. (The last factory making such shoes in China closed in the late 1990s; towards the end, the business — in the far-northeastern Chinese city of Harbin — was producing just 300 pairs a year.)

“I couldn’t understand why they were hurting me and I screamed for my mother. They said I had to have my feet made small or I would disgrace the family”

Zhu Shao Qiong, 96

Dwarfed by translator Sally’s size-36 Adidas sneakers, Zhu’s shrunken feet cannot be longer than 10cm in length. She totters with the help of a wooden cane topped by the carved head of a dragon.

Now 96 years old, Zhu says her mother passed away when she was just five. She was then cared for by her maternal grandmother, who bound her feet the following year.

“I couldn’t understand why they were hurting me and I screamed for my mother,” Zhu says. “They said I had to have my feet made small or I would disgrace the family. Afterwards, I couldn’t move. It was as if my feet were on fire. Relatives brought food to my bed, but I couldn’t even eat, I was in so much pain.”

Zhu claims to be of the noble Zhu family (the main attraction in the nearby town of Jianshui is the Zhu Family Garden, a 20,000-square-metre complex of more than 40 residences that served as home to the clan, which made its fortune in tin and opium). Though she vividly recalls the intense suffering of having her feet crippled for life, she bears no resentment.

In fact, Zhu says her grandmother was being kind, not cruel, to her. “It was thought that only girls with small feet were pretty and had value,” she says. “Only girls with small feet would find a husband from a good family, so it was the right thing for her to do.”

“We have to remember that before the 20th century, foot binding was not an imposition or torture that women would shriek from,” says Ko. “On the contrary, it was a privilege that they would embrace — if they were privileged enough to do so.

“Not all women could afford to have their feet bound, only those who could find an alternative means of livelihood indoors. In Yunnan, this meant those who had the skills and means — a loom, for example — to weave cloth at home.”

Like Yang in Liuyi, Zhu was also kept hidden when authorities came snooping. “When inspectors were sent here to make sure [binding] wasn’t happening anymore, our families would hide us away.”

AT THE ORNATE WODDEN entrance to a residential courtyard nearby, Zhu’s 95-year-old friend Xiong Xiufeng relaxes in the shade while a group of her middle-aged neighbours shell peas at her dainty feet. Like Zhu, she has clearly made an effort with her appearance — she wears a similar blue smock to that of her friend, as well as velvety black trousers.

Her doll-like shoes, no bigger than an infant’s slippers, are crafted from star-spangled aubergine corduroy.

Xiong’s mother began binding her feet when she was six. “I couldn’t even move, it was so painful,” says Xiong, who came from a middle-class family of salt traders, and whose father died leaving eight children behind.

“They wouldn’t let me take the binding away no matter how great the pain. It was wrapped on tight, so I couldn’t get it off, and my mother would beat me if I tried. At that time, if your feet were large, no man would marry you; no other family would have you.”

At the age of 14, Xiong married a tin miner from a respectable family, which, she says, may never have come to pass if her feet had not been bound. The couple had six children, but when asked if she had ever thought of binding her own daughters’ feet, she answers immediately and emphatically: “Absolutely not. This is something from the old society. Those days are gone.”

Xiong is clearly proud, however, of her strikingly unusual shoes, which she made herself, and she twists and turns to show them off from every angle. She complains that her poor eyesight means that a simple pleasure she once relished is now a thing of the past.

“I used to enjoy making shoes very much,” Xiong says, “but my eyes just can’t cope any more.”

Asked how many pairs of shoes she has, those eyes suddenly brighten, Xiong’s reedy voice rises and she eagerly snatches at translator Sally’s hand. In a moment, it is absolutely apparent that, although Xiong was born in an era when China was a very different country, some things — for a certain type of lady — were the same back then as they are today.

“Oh, I have so many shoes, but not as many as when I was younger,” she says. “I have more than 20 pairs, I think — I have a big box full of them. I’ve always liked shoes.” ◉

Versions of this story ran in Frankie magazine in Australia (PDF here), The Week in the UK and Post Magazine in Hong Kong (PDF), all in 2013.

SHARE