Rejected by both the state and their families, the children of serious criminals in China can also be victims of their parents' wrongdoing. The luckiest get a chance to thrive thanks to charitable NGO Morning Tears.

NIU NIU SCURRIES by as fast as her little legs will carry her, and she chews on a strawberry and chuckles as she is chased around the table. The toddler’s guardian, Kou Wei, also giggles as she shoos the three-year-old outside and into the afternoon sunshine. Kou’s job is to care for Niu Niu and youngsters like her — to watch over the sons and daughters of murderers, gangsters, rapists, drug smugglers and other criminals who have been executed or imprisoned for decades in China.

Methodically, one after another, Kou tells the stories of some of the 44 waifs in her care. They are heartbreaking tales of shattered young lives — of violence, trauma and tragedy.

Kou begins with nine-year-old Huan Huan, whose mother killed her father after suffering years of domestic abuse. Huan Huan’s grandfather, in revenge for the death of his son, sold her two sisters.

Xiao Lu, at the age of seven, witnessed her parents beat a man to death. Xiao Yi saw her father slaughter her mother, and Niu Niu is the daughter of a pimp who was jailed when she was just one year old. With the family’s only source of income gone, Niu Niu’s mother abandoned her and her brother.

“We tried to send Niu Niu to kindergarten, but she refused to go, so we keep her here,” says bespectacled Kou, who is the director of the Ai Tong Yuan Coming Home Project, one of only a handful of such specialised childcare facilities in the world’s most populous nation. Despite the harrowing nature of her work, 34-year-old Kou laughs and smiles easily. “The other kids complain because when they are at school, Niu Niu goes through their things and takes whatever she needs.”

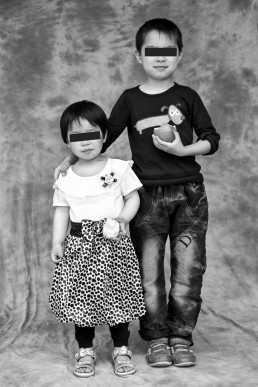

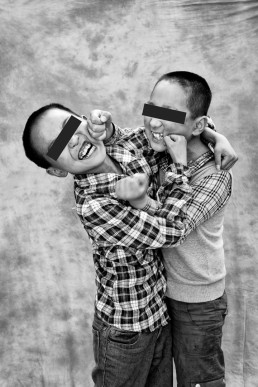

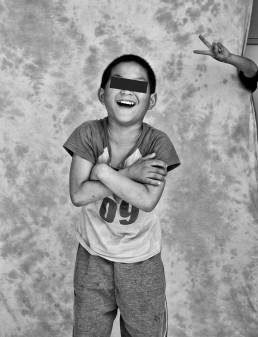

Niu Niu (left), aged three, and Tong Hao (right), nine, are sister and brother. Their father is in prison for 10 years, says Kou Wei of the Ai Tong Yuan Coming Home Project, for forcing ‘many’ women into prostitution. Their mother abandoned them. Photo and opening montage: Palani Mohan

THE AI TONG YUAN facility is located an hour’s drive east of Zhengzhou, capital city of central China’s Henan province. The discreet compound comprises four buildings painted in a peppy apricot-yellow, a basketball court and a playground. The children sheltered here, supervised by adult caregivers, live in five “family units” — essentially self-contained apartments — in the largest of the buildings. No-frills interiors are scuffed and grubby at child height. Cardboard boxes of second-hand toys are anything but overflowing.

“The kids have been through extremely traumatising events,” says Koen Sevenants, Belgium-born founder of Morning Tears, a non-governmental organisation supporting the welfare of such youngsters in China. “In many cases there has been domestic violence. Many have been subject to physical abuse, and sexual abuse in some cases.

“Children who have seen a mother brutally beaten … that can be more traumatising to a child than being beaten themselves. That is a parent they love and they want to protect that parent, but at that age they cannot.”

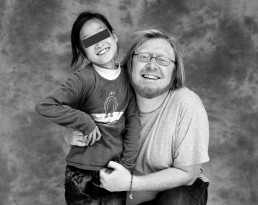

The children at Ai Tong Yuan clearly adore “Uncle Koen” and the older lads leap onto his broad shoulders, pleading noisily with Sevenants to arm-wrestle or play rock-paper-scissors. In his work uniform of scruffy jeans and baggy T-shirt, and with his mop of unruly blond hair and ginger beard, the 1.8-metre and burly European must appear, in their youthful eyes, like a bear — a teddy bear of seemingly inexhaustible playfulness and patience. Sevenants, 41, holds a doctorate in psychology. He has worked for aid groups all of his adult life.

“These are the children nobody wants,” he says, explaining that the offspring of convicts — still having grandparents, perhaps uncles and aunties — are not recognised as orphans by the Chinese state. “Very often relatives don’t want them. In cases of murder resulting from domestic abuse, the father’s family don’t want them because they see the mother in the children. The mother’s family see the father.”

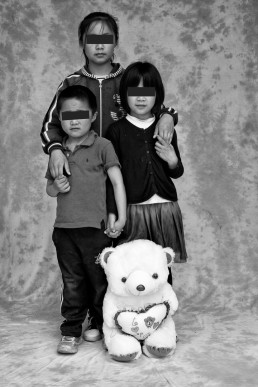

Pan Pan (left), aged 6, Xiao Lu (centre), 13, and Lu Lu (right), 8, are siblings. Their father was one of China’s army of migrant workers, leaving the countryside to make a living in the city.

With her husband away, their mother suffered the repeated attentions of the son of a local village chief. She fought back, but the man persisted, even continuing his harassment once her husband had returned. A fight between the three resulted in the man being beaten to death. The couple received life sentences. Photo: Palani Mohan

Huan Huan is nine years old, comes from a rural family and has two younger sisters (China’s one-child policy is not enforced as rigorously in the countryside, especially when offspring are girls). Their father was violent towards their mother, who — with the help of her own father — one day fought back. The brawl resulted in the husband’s death. Huan Huan’s mother was sentenced to life in prison, her maternal grandfather to 10 years.

Huan Huan’s paternal grandparents held a grudge and yet took custody of the three girls. Two years ago, they sold Huan Huan’s sisters, then aged five and three. ‘The grandparents will not tell us, or even the police, where they are,’ says Kou. ‘They want to punish Huan Huan’s mother.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

LESS THAN THREE hours west of Zhengzhou by air-conditioned express train, Xian, the provincial capital of Shaanxi, is one of China’s most ancient cities and home to the Terracotta Warriors. The Morning Tears-supported Sanyuan Children’s Village is a 90-minute drive to the north.

Unlike tranquil Ai Tong Yuan, the Sanyuan sanctuary, home to 47 children, rests beside a busy road. Articulated trucks roar by at speed, thrashing up dust and blasting their horns, and the main building is an austere construction that has been pleasingly overwhelmed by bottle-green ivy on the side of its shaded playground.

The playground has a climbing frame, a bench swing and canary-yellow exercise machines. While lunch is being prepared, children scrub their faces and hands from stainless-steel kitchen bowls at the ping-pong table.

Pictures torn from glossy magazines, of boy bands and coquettish movie starlets, add splashes of personality to the paint-flaking dormitories in which the children sleep

Sanyuan director Yang Biao, 50, is welcoming but cautious of strangers. When asked for details of children in his care, he initially and protectively sidesteps the request. Yang relents over two days, conceding that he can be wary of outsiders’ motives.

Like Kou before him, Yang produces brown-paper A4 envelopes containing individual human stories. Yang tells of one crime-orphaned youngster who arrived at Sanyuan when she was 13. Her family had lived in a mountainous area and the child’s father had been a roaming carpenter who became romantically involved with a woman in another village.

The lovers decided to kill the carpenter’s wife. Poison failed but a nail hammered into the woman’s head, Yang says, proved effective. The carpenter was executed.

“We have a boy, he is 13 now, who came to live with us last year,” says Yang. “His mother had been a teacher in Xian city. She and members of her family beat his father to death after a quarrel over gambling, and [the father’s] drug taking and drug dealing. The mother just couldn’t take it. She was jailed for 20 years.”

A portrait of Mao Zedong — the same airbrushed image that looks out across Tiananmen Square in the capital Beijing — is fastened high on the wall at the front of the Sanyuan operation’s basic classroom. Pictures torn from glossy magazines, of boy bands and coquettish movie starlets, add splashes of personality to the paint-flaking dormitories in which the children sleep, perhaps hugging the threadbare stuffed toys that are now scattered across their beds.

Occasionally, Yang reveals, children arrive at Sanyuan as babies. One child, now aged four, was newly born. “When her parents were arrested for drug dealing, her mother was ready to give birth,” Yang says. “The father was locked up, but the woman was taken to a hospital. Within a week of the baby’s delivery, the mother fled.”

Yang says the infant had not been given a name, and light drizzle was falling when police officers brought her to Sanyuan, where staff christened her. Xiao Yu means “Little Rain”.

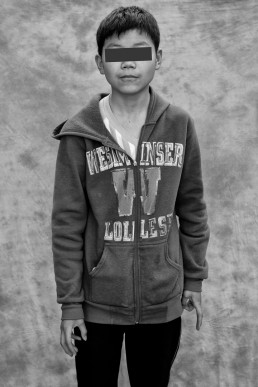

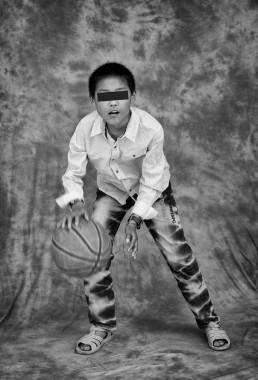

Yu Kun, 14, comes from a poor family and, according to Yang Biao, director of the Sanyuan Children’s Village, his early years were plagued by domestic conflict. When Yu Kun was three years old, his father beat him so badly that his mother killed her husband with rat poison, cutting his throat to ensure he was dead. Having pleaded mitigating circumstances, Yu Kun’s mother has been imprisoned for life. The boy has been cared for since 2004. Photo: Palani Mohan

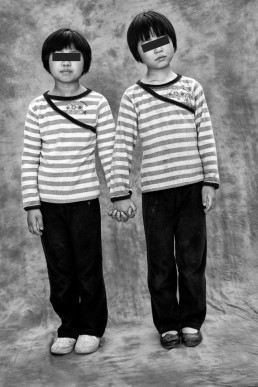

Xiao Ze (left), aged 10, and Xiao Wei (right), 12, are brothers. Following a disagreement, their father shot and killed a local villager with his hunting rifle in 1995. The father was captured and executed in 2005 after 10 years on the run.

The boys lived with their grandfather after their father fled and were taken in at Sanyuan in 2009, when their ageing guardian could no longer cope. One hour after this photo was taken, the boys’ grandfather took them home for the May Day holidays. Photo: Palani Mohan

THE ORIGINS OF Morning Tears can be traced back to 1996, when four Chinese judges — obliged by law to hand out death sentences and lengthy jail terms — recognised the plight of the children left behind and decided to act, financing from their own pockets three facilities in and around Xian.

The judges’ cash drained away quickly, however. Their first facility closed after just two years. Three years in, and the second space wound up. The third was about to expire when Sevenants, based in Beijing at that time and employed by Handicap International as country manager for China and North Korea, discovered it. “[A colleague and I] started out as volunteers,” Sevenants says, shrugging at the memory of their naivety. “And then everything spun totally out of control.

“One day, you realise that you are thinking a lot about the children. You can’t sleep when they have problems. Anyway, after a while, we said, ‘This has gone much too far.’ We decided to source the money [required] to keep the kids going for two years and hand everything over to local people. For us, it would end, we could get on with our lives. And that’s what we did. And that went well for … about two weeks. We couldn’t walk away, we just couldn’t, and so we decided to do things properly.”

Today, Morning Tears has 100 or so staff in China, with about 40 of those being volunteers. It shores up four core projects: Ai Tong Yuan, Sanyuan and one other facility near Xian, and another close to Beijing. There are smaller operations in the cities of Chengdu and Wuhan. Morning Tears supports — at various levels, from full-care to individual assistance with schooling — about 580 children. More than 1,000 youngsters have benefitted since Morning Tears was founded. Its earliest wards are now adults.

Those numbers are just drops in an ocean of juvenile despair, however. According to the Chinese Ministry of Justice, there are 600,000 children of convicts in the country. Many are without guardians and the youngsters beg, hustle and thieve on the streets to survive. Childhood trauma manifests itself in self-harm, anti-social behaviour and nightmares, says Sevenants, and many young sufferers will also become convicts in a pan-generational cycle of misery.

The number of people executed each year in China, meanwhile, is a state secret. International watchdogs claim the country kills thousands of its citizens annually — more than the rest of the planet combined (the United States put 46 people to death in 2010). Capital punishment is employed for more than 50 crimes in China, ranging from tax evasion to murder (mitigating circumstances are considered in individual cases). Executions have traditionally been carried out by a single gunshot to the head. Lethal injection has come to the fore in the last decade.

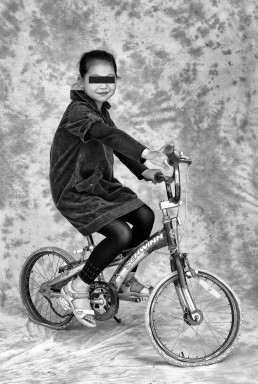

Nine-year-old Ming Ming arrived at the Ai Tong Yuan facility at the age of six. Her parents are in prison for 11 years for stealing cable to sell as scrap. ‘She finds it difficult to visit her parents [who are in different prisons] because her father always complains about her mother, and her mother complains about her father,’ says Kou. ‘The parents can’t see each other, so they argue through the child. Ming Ming doesn’t like prison visits.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

Liu Fei, aged eight, arrived at Sanyuan in March. His parents had been jailed for 20 years for being members of an organised gang of car thieves. The gang had been operating for at least five years, and for much of that time — since Liu Fei was three — the boy had been kept with the family’s sheep. ‘He lived with the sheep, he ate with the sheep,’ says Yang. ‘When he came here he could not walk properly. He has problems communicating.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

BACK AT THE AI Tong Yuan Coming Home Project, the children have finished a simple lunch of noodle soup and steamed buns. Some take naps. Some bend over exercise books with colouring pencils, sketching houses, apple trees and rainbows. Huan Huan watches television and Sevenants is reading a story to cross-legged children in one of the dormitories. Niu Niu plays with a discarded mineral-water bottle.

Inside the two-metre-high wrought-iron fence and wall that surround the compound, the young residents of the project are safe amongst their own. Life can be less secure beyond the perimeter, with the children of convicts spurned for bringing bad luck and for carrying criminal tendencies in their DNA.

Kou cites the case of Meng Meng, who is now 12. Meng Meng’s father was incarcerated when she was four, and her mother deserted her. Meng Meng then lived with her grandfather, but his neighbours refused to accept the girl into their community. Through those neighbours, Meng Meng discovered that her father was a rapist. “She refuses to visit her father in prison,” says Kou.

Kou tells of Xiao Yan, another 12-year-old, who arrived when he was eight. The boy’s father is in prison for life for theft. Xiao Yan’s mother rejected him and he was sent to live with his uncle. Neighbours in his uncle’s village shunned Xiao Yan as the offspring of a felon. “He became a troublemaker,” Kou says. “[Xiao Yan] told me that he didn’t want to be that way, but he couldn’t make people understand that he was not a bad kid. In his mind, he was left by his father, by his mother, then by his uncle. Nobody wanted him.”

“Girls, maybe 14 or 15 years old, have been taken away because relatives want to marry them off. I worry when a girl of that age is taken from us”

Morning Tears founder Koen Sevenants

Sevenants believes it is preferable for children to be cared for by family members, and there have been instances of children being taken away after years in Morning Tears’ care by relatives. Blood ties, however, can prove less than ideal.

“A child might go to an aunt or a grandparent, but their education could stop,” Sevenants says. “They will have to earn their keep, they might be beaten and then, after a time, they can be cast aside and traumatised for a second time. We’ve had kids arrive back here with [bruises] and cuts. They are underweight, they haven’t been to school for years …”

There are many reasons, Sevenants believes, why relatives might collect children. “We had one case of pure child torture — a brother and a sister, 13 and 10 years old,” Sevenants says. “Their parents had been executed for drug smuggling and an uncle was convinced that money had been hidden away. The uncle tied [the children] to chairs and beat them for information. When he failed to find money, he just returned them to us.”

Also troubling is the fact then when a young woman marries in rural China, tradition dictates that the groom’s family must pay the bride’s kin. “Girls, maybe 14 or 15 years old, have been taken away because relatives want to marry them off,” says Sevenants. “I worry when a girl of that age is taken from us.”

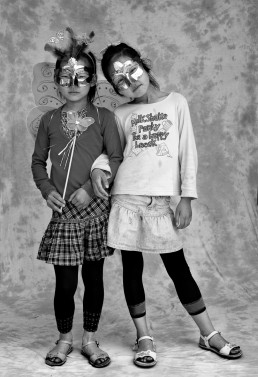

The father of Yi Li (left), aged nine, is in prison for stealing. Her mother divorced him, remarried and left. Yi Li has been cared for at Ai Tong Yuan for three years. ‘Yi Li is an angel,’ says Kou. ‘She’s patient, she helps the caregivers and she’s very smart, top of her class … everyone loves her.’

The parents of Dan Dan (right), also nine years old, are in jail for poisoning a man who regularly made unwelcome advances towards her mother. They were sentenced to death for murder with a two-year reprieve, meaning their sentences could be commuted to life imprisonment. ‘Dan Dan is a very pretty girl and she knows it,’ says Kou. ‘She’s not a great student. Every day her caregivers complain because she will spend an hour or more on her hair.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

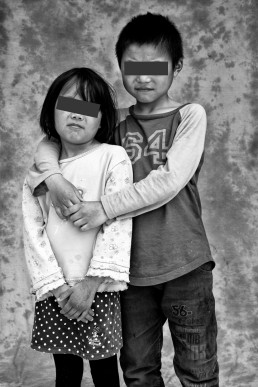

Siblings Xiao Wan (left) and Xiao Yi (right) are aged nine and six respectively. Their father received the death sentence for murdering their mother. His sentence has been deferred for behaviour appraisal and may be commuted to life. ‘They have visited their father in prison, but they think he is the devil,’ says Kou. ‘They have a lot of nightmares.’

Kou has found the case difficult to handle. ‘Xiao Wan told me that his father had often been abusive to his mother and there was always violence at home,’ she says. Photo: Palani Mohan

OCCASIONALLY, EMOTIONALLY damaged children will reject protection, as was the case with Xiao Sheng, whose mother stabbed and killed his father when the boy was just five. She was executed and Xiao Sheng was cared for until he was 14. “He was eaten up by anger,” says Sevenants. “He would not calm down. He was convinced his mother had been innocent. He wanted revenge and he left us at too young an age.” With nowhere else to turn, Xiao Sheng took a job in a coalmine. He died in a mining accident at the age of 15.

In the same way that communities have scorned individual children, Morning Tears projects have also come under attack. “In 2000 we had a security problem and had to move one of our facilities,” Sevenants says. “Our children were being beaten.”

A public-relations exercise was put into place, to reposition the home as a community project where all would be welcome. The walls would come down. “We wanted to hold film showings in the evenings, invite local children to join us,” says Sevenants. “We had to give it up, build a wall again, lock the gates — not to keep our kids in but to keep local people out; to stop them from stealing things and treating our children badly.”

And the psychologically exhausting headaches do not stop there, with the pain of the children transferring to their adult protectors. Kou, especially, has confronted demons.

Kou’s mother killed her violent father in 1996, while she was studying English at university in Xian. “I am one of [these children]. I feel how they feel, and I can show them something, but I’m not always sure what it is,” Kou says. “They feel safe with me. It’s difficult to put into the words, but I strongly believe that the children understand me.”

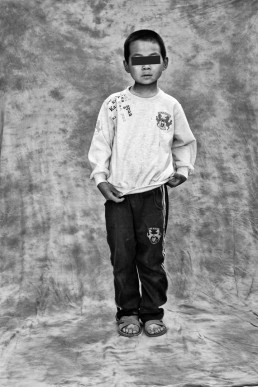

Jia Yu is 11 years old. His father is incarcerated for stealing and his mother abandoned the boy. ‘Many of these families are very poor and depend totally on the father,’ says Kou. ‘When a father goes to prison, there is no income at all, so mothers often leave and start again.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

Xiao Yan, 12, arrived at Ai Tong Yuan when he was eight. His father is in prison for life for robbery. His mother abandoned him. ‘He was a very troubled boy [on arrival], having fights with caregivers and other kids,’ says Kou. ‘Now he’s a sweetheart.’

Kou says Xiao Yan suffers from abandonment issues. ‘We were holding a drawing exercise, helping the kids to express their feelings, and he drew a black heart,’ she says. ‘I asked him why the dark colour and he said, ‘This is the feeling I have for my mother.’’ Photo: Palani Mohan

SEVENANTS HAS ALSO struggled with emotional fall-out. He no longer attends when children visit parents in prison. “There’s a lot of pain involved and it gets into your system,” the Belgian says through a sigh. “They say things become easier with time, but I find it more difficult now than in the past. I try to keep distance, to limit involvement. I had to seek personal assistance at one point, to help me cope with things, to digest things.”

Caregiver Hong Li, 30, has a five-year-old son of her own. “The first year, when new children arrived and I heard their stories, I would find it so heartbreaking,” Hong says. “I couldn’t control myself. I cried a lot.”

These days, Sevenants focuses on the fundraising side of Morning Tears, which now has presence in the United States, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, France, Italy, Germany and Spain, as well as mainland China and Cambodia. Basic care for each Chinese child costs around Rmb350 (then about US$6) a month.

“That not only includes food, clothes, housing, but also a meaningful life with school and hobbies, with psychological and personality development assistance,” he says. “But prices are going up and inflation is a problem. Last year the price of pork [in China] rose fourfold.”

Companies and corporations … when they hear ‘death penalty’ and ‘criminals’, they worry that we might be a human-rights organisation that opposes the Chinese government

Sevenants on drumming up funding

The global economic crisis has curtailed donations, but Sevenants has a more fear-led than finance-driven challenge to overcome. “People are afraid by what we do,” he says. “Companies and corporations, of course, donate money to community causes. When they hear ‘death penalty’ and ‘criminals’, they worry that we might be a human-rights organisation that opposes the Chinese government. They don’t want to be associated with us. They are scared of us.”

That ill-informed attitude is frustrating, especially considering that Morning Tears and the Chinese authorities collaborate. The Ai Tong Yuan Coming Home Project is jointly operated by Morning Tears and the state-run Zhengzhou Children Protection Centre. Sevenants is a consultant to the Chinese government in the upgrade of child-protection laws and procedures. Morning Tears is legally registered as an NGO in China, enabling it to issue state-approved receipts so that donations are tax deductible.

In 2010, in fact, China’s central government rewarded Morning Tears with its ultimate stamp of approval, presenting the NGO with the China Charity Award — the nation’s most prestigious honour in that field. “Actually, I think they may have given the award to help us,” says Sevenants. “To show that it’s okay to support what we do.”

Coming from a poor rural family, Li Wei (left), aged eight, has been cared for at Sanyuan for two years. Her father was a migrant worker making a meagre living as a labourer in Xian. When his employer held back his wages, Li Wei’s father attacked the man and received seven years for assault. Her mother suffers from schizophrenia.

The mother of Wang Yi (right), also eight, suffers mental-health problems and left the family in 2006. Her father died in 2009 of pneumonia. She has been cared for at Sanyuan since 2010. Photo: Palani Mohan

‘In the past, 90 per cent of the children we supported were from rural, financially disadvantaged backgrounds,’ says Koen Sevenants, the general director of Morning Tears. ‘That has changed and there is more diversity these days. Urban drugs have played a large part, and we are increasingly taking in kids originally from quite well-off families.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

WITH THE SUN SETTING behind a neighboruing factory, the oppressive heat of the day subsides and the children of the Ai Tong Yuan Coming Home Project have finished classes. Dan Dan, aged nine, claps and slaps and grins through a lively session of patter-cake with Kou. Eight-year-old Lu Lu slaloms by on the single skateboard shared by all of the 44 children. Dan Dan and Lu Lu are daughters of convicted murderers.

Two studious children attack their homework, standing at the outdoor ping-pong table. Faded sweatshirts and battered canvas sneakers drip-dry on a railing and weary caregivers, who have been digging an allotment and planting peanuts, wipe sweat from sun-darkened brows. If the peanuts flourish, sweet potatoes and melons, perhaps even Niu Niu’s favourite strawberries, might follow.

Despite the myriad problems they confront every day, Kou, Sevenants and their colleagues agree: the rewards of their cause outweigh the heartache. “Relearning how to play, to trust and make attachments, is very important,” Sevenants says. “We give children a safe environment in which to do that. It’s a glorious moment, it feels fantastic, when you see a child, who was terribly traumatised on arrival, start to play again.”

Caregiver Hong, who has been with the facility of three years, concurs. “I’ve had many chances to take jobs with better salaries, better conditions, but then I start to feel upset,” Hong says. “I end up saying no. The children and I have become so close.”

Hong’s friend and colleague Dandan, 22, has also been a caregiver for three years. “I’ve seen many positive changes,” she says. “Little Fanfan [believed to be aged seven] arrived two years ago. She wouldn’t speak — not a single word — for two or three months. She would cry all the time. She would kick and hit out at anyone who came close. Now she’s happy and polite. She loves to share time with the other children.”

For Kou, the experience has been especially life-affirming, assisting her in dealing with her own distressing past. “The way the kids express their inner anger … I can see that, well, maybe that is not always the right way,” Kou says. “Sometimes [in the past], when I have reacted to things, I have not always been able to control myself, to see the right way and the wrong way. The children have taught me a lot.”

AN HOUR PASSES and stars are appearing in the clear evening sky. Caregivers are rounding up the children to clean their teeth before bed.

Niu Niu drops the day’s last strawberry into the dirt and one of the project’s two pet dogs — strays taken in from the neighbourhood — sniffs at the discarded fruit. Niu Niu fashions her chubby fingers into a V and raises them towards the photographer’s camera. She looks directly into the lens, her dark eyes sparkle and she smiles an innocent’s smile. ◉

Children’s names have been changed. Their stories and censored portraits have been approved for publication by their guardians at the Ai Tong Yuan Coming Home Project and Sanyuan Children’s Village.

This long-form feature ran in Hong Kong's Post Magazine and now-defunct Australian website The Global Mail in early 2013. They are no longer online. Morning Tears' Facebook page is here.

SHARE