As the poet's 100th birthday approaches, a Chinese academic is working to introduce the Welshman's wistful, frequently surreal but always rewarding words to his homeland.

DYLAN THOMAS NEVER visited China during his short life of 39 years. The Welsh poet — much loved for his innovative use of language and intoxicating imagery — did, however, refer to the country in a revised version of his Reminiscences on Childhood, which he read aloud on radio in 1953, the year of his death:

“I was born in a large Welsh town at the beginning of the Great War, an ugly, lovely town — or so it was and is to me — crawling, sprawling by a long and splendid curving shore where truant boys and Sandfield boys and old men from nowhere beachcombed, idled and paddled, watched the dock-bound ships or the ships streaming away into wonder and India, magic and China, countries bright with oranges and loud with lions…”

The “ugly, lovely town” Thomas spoke of on the BBC’s Welsh Region Home Service was Swansea, where the author of haunting poems And Death Shall Have No Dominion and Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night, and the polyphonic “play for voices” Under Milk Wood, was born 100 years ago on October 27.

And now his dream-like musings of a journey to China are scheduled to become an after-life reality.

MULTIPLE EVENTS HAVE been arranged for the centenary of Thomas’s birth, including a 36-hour “Dylathon” of readings of his works at Swansea Grand Theatre, timed to end on the hour of his delivery. The readings will be made by the Prince of Wales, actor Sir Ian McKellen and former Wales rugby captain Ryan Jones, among other notable fans.

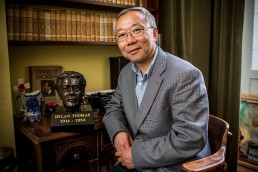

And earlier this year, on a less star-studded but similarly groundbreaking occasion, a low-key academic also visited Swansea — on a mission to produce a definitive guide to the writer’s oeuvre in Chinese. Professor Wu Fu-sheng has now translated 25 key pieces of Thomas’s work. A book is scheduled for release in 2015.

“Personally, I like Dylan Thomas’s handling of the English language and poetic conventions to create his unique style of poetry,” says Wu, 55, who was raised in the northern Chinese city of Tianjin and today is professor of Chinese literature and comparative literary at the University of Utah in the United States.

“I find his description of nature very beautiful, and his pantheistic, poetic vision or representation of life and death — the ‘process poetics’ — very moving.”

“Thomas deliberately challenges and even violates the norms of English language in his poetry, making his poems difficult and obscure even to English readers”

Professor Wu Fu-sheng

Having worked in a textiles factory as a young man before attending Tianjin’s Nankai University, Wu headed to the US in 1990 to obtain his doctorate in literature. Thomas, by contrast, was disinterested in formal studies, leaving school at 16, with much of his poetry appearing in print while he was still a teenager.

Heavy with symbolism and dabbling in surrealism, Thomas’s creations, though refined in craftsmanship, were always tricky to pigeonhole. Wu says they still pose “intriguing issues” for English-Chinese translation.

“Thomas deliberately challenges and even violates the norms of English language in his poetry, making his poems difficult and obscure even to English readers,” he says. “But in poetry, obscurity and uncertainty sometimes can create multiple meanings, which add to the depth of the poems in question. In Dylan Thomas’s poetry, this is particularly true because he loves to use puns.

“Unfortunately, a translator must often choose one possibility out of several, thereby limiting the scope of the poems. Thomas’s poetry exposes in acute ways the limitations of translation.”

WU VISITED THOMAS’S birthplace in Swansea: the humble, semi-detached, red-brick house of the writer’s family at 5 Cwmdonkin Drive, where he lived until he was 19 and wrote many of his finest compositions. There, Wu read aloud, in Mandarin, excerpts from Thomas’s poetry, including Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night, for an invited audience.

“It was really an inspiring experience,” Wu says. “I saw the room where he wrote many of his poems, and his father’s study where he often hid himself as a teenager.”

Wu found his sojourn to the Welsh fishing village of Laugharne, where Thomas, his wife and newborn son lived a hand-to-mouth existence in the late 1930s, especially poignant.

“There, overlooking Thomas’s ‘heron priested shore’,” says Wu, “listening to his recorded reading of Poem on his Birthday, which is one of his last poems, written there, I came to a much better understanding of many of his works, especially Over Sir John’s Hill — also written there, in his ‘writing shed’, by which I found myself fixated for quite some time during my visit — one of my favourites and a moving meditation on the process of life and death.”

Wu has translated Thomas's work into Chinese. Video: Swansea University/YouTube

PROFESSOR JOHN GOODBY, from the department of English at Swansea University and a world authority on Thomas, was instrumental in bringing Wu to Wales.

The recent author of The Poetry of Dylan Thomas: Under the Spelling Wall, Goodby believes Thomas’s work breaks down the barriers between “high” and “popular” art, and describes his manipulation of the English language as “profoundly satisfying, provocative and beautiful”.

“In a world in which politicians, businessmen and administrators are busy trying to reduce language to dead, jargon-ridden discourses, he reminds us that we are all capable of using it for very different ends, or — perhaps best of all — for no end, purely for imaginative play,” Goodby says. “When Thomas begins a poem with, ‘Once below a time’, we think, ‘Yes, why not ‘below’, rather than ‘upon’?’”

“I think there will always be two Dylans: Dylan the great poet and writer — the words on the page — and then Dylan the larger-than-life character who packed so much into his 39 years”

Antiquarian book dealer Jeff Towns

Swansea-based antiquarian book dealer Jeff Towns has spent four decades keeping Thomas’s legacy alive, He even has the closing lines of his poem Fern Hill tattooed on an arm (“a 60th birthday present from my wife,” he says).

The self-styled “The Dylan Thomas Guy”, Towns has personally aided individuals as diverse as Beat Generation poet Allen Ginsberg, illustrator Ralph Steadman and Prince Charles to boost their knowledge of Thomas and his writing.

“Throughout his life, and even more since his tragic early death, he has continued to reverberate with popular culture,” says Towns, citing Thomas’s influence on singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, and how the poet made the cut to appear amongst the montage of faces on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album.

Others famous fans include former US presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, Mick Jagger, Charlie Chaplin and actor Pierce Brosnan (who has a son named Dylan Thomas Brosnan).

IN THE YEARS before his untimely death in 1953, Thomas acquired a reputation — which he encouraged — as a hard-living drunk and hell-raiser. Dying young while on a tour of New York resulted in the creation of a James Dean-like myth around the writer. (The post mortem provided a less glamorous version his death: the primary cause being pneumonia, with pressure on the brain and a fatty liver as contributing factors.)

To this day, while Thomas is celebrated as one of the most accomplished poets of the 20th century, that semi-fictional image of the doomed romantic has often overshadowed his writing.

“I think there will always be two Dylans: Dylan the great poet and writer — the words on the page — and then Dylan the larger-than-life character who packed so much into his 39 years,” says Towns.

Goodby also believes that the cult of Dylan Thomas has had a peculiar but positive effect in keeping his legacy alive. “All of Thomas’s work remains in print because of the legend, and the large general readership means that there is always a chance that some will seek to go beyond the wisecracks and the tales of drunkenness and debauchery,” Goodby says.

Though some of Thomas’s poetry had been translated into Chinese in the past, Wu’s attempts will be accompanied by critical annotations and explanations, offering insights into his life and character, and a more rounded portrayal of the writer. “These features will surely be of great help to the Chinese readers to appreciate this great but difficult poet,” Wu says.

“The legacy of Thomas’s work is complex and profound,” adds Goodby.

“He had a major impact on later English-language poets, and because his poetry deals with the universals of conception, birth, love and death … he has had an impact beyond the Anglophone world, too — in Germany, France, Poland, Argentina, South Korea, West Africa and, hopefully soon, in China.” ◉

This feature ran in Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post in October 2014. Download PDF.

SHARE