In 1935, the brother of James Bond author Ian Fleming made a 3,500-mile overland trek along the Silk Road from Peking to Kashmir. His memoir of the journey is a masterclass in English understatement.

POPULAR CULTURE IS awash with tales of bumbling Brits getting into scrapes abroad. But decades before Michael Palin set off “across the Andes by frog” in television’s Ripping Yarns, and the “shagging wagon” of the Inbetweeners conked out in the Aussie outback, Peter Fleming — raffish big brother of James Bond author Ian — set off on a 3,500-mile road trip from Peking to India.

His resulting News from Tartary has been celebrated/blamed for cementing the literary template for the amateurish adventurer from Albion ever since, crazy-paving the way for the self-effacing, accessible style of travel writing embraced by everyone from Eric Newby and honorary Brit Bill Bryson to Geoff Dyer.

In 1935, when 28-year-old Fleming and his resourceful companion, the Swiss adventurer Ella “Kini” Maillart, set off on their journey, the region of Tartary — as he writes — was “not strictly a geographical term, any more than Christendom”. Tartary referred to the sprawling expanse of terra firma that today would encompass northern China, Mongolia and central Asia, and often idealised as the ancient “Silk Road”.

With specialist gear only amounting to “a rook rifle, six bottles of brandy and Macaulay’s History of England”, the odd couple’s epic, seven-month trek was the antithesis of the “scientific”, data-collating expeditions of the Victorians — with their huge retinues and masses of equipment. The 1930s, after all, was the finger-clicking jazz age and improvisation would be the duo’s watchword.

As a special correspondent of The Times in the ’30s, Eton and Oxford-educated Fleming explains in the book’s preface that there were two reasons for the journey. With Tartary essentially a no-go area due to political turmoil and banditry, and a black hole for news, he was to gather intelligence for his employer. The second reason was simply “that we should enjoy it”.

But while Fleming’s writing is peppered with disarming, Wodehouse-like asides, News From Tartary is in the main a controlled exercise in thin-lipped English understatement. If travel scribbling inherently leans towards exaggeration, here the hyperbole lurks in the author’s sustained belittling of hardships the couple face and their achievement. If Fleming boasts, it’s of his inadequacies and failings.

THE WRITER MAKES a stand early in the text, explaining that while he and Maillart differed “widely in character and temperament, we had one thing in common”.

“We were united by an abhorrence of the false values placed on what can most conveniently be referred to by its trade-name of adventure … we were repelled by the modern tendency to exaggerate, romanticize, and at last cheapen out of recognition the ends of the earth and the deeds done in their vicinity.”

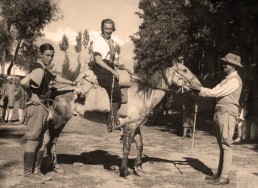

That’s not to say the going proved easy. By train, overloaded truck, wheezing bus, hunched horses, injured camels and occasionally on blistered foot, Fleming and Maillart attack some of the most inhospitable terrain on the planet, crossing the Gobi and Taklamakan deserts and Himalayan passes, suffering ferocious snow and sandstorms, as well as extremes of heat and cold.

Along the way they encounter exotic Mongol princes, Tibetan lamas and Tungan caravans, and gather insights into now-vanished ways of nomadic life, all against a turbulent political backdrop, with the Chinese communists in regular skirmishes with the ruling nationalists, Japan occupying Manchuria and exiled white Russians roaming the land searching for a new home.

The prince of Dzun ought “to be a romantic figure, a true-blue, boot-and-saddle, hawk-on-wrist scion of the house of Chinghis Khan, with flashing eyes and a proud, distant manner and a habit of getting silhouetted on skylines. But God, not Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, made the Prince”

Peter Fleming

I have travelled much of the route taken by Fleming — by air-conditioned Land Rover — and can attest to the vast scale and utter bleakness of much of the landscape. Fleming conveys the near-hallucinatory monotony — “the world around us jigged liquidly in a haze” — and the simple but utter bliss of arrival, as when their caravan reaches the oasis of Cherchen in the Taklamakan.

“Wonder and joy fell on us … Trees lined the path, which threaded a patchwork of neat little fields of hemp and rice and barley. Men of gentle appearance in white robes lent on their mattocks to watch us pass … hands were pressed, beards stroked, curious glances thrown at us. Everywhere water ran musically in the irrigation channels.”

But on the whole Fleming — who, in his earlier travel account Brazilian Adventure (1933), described São Paulo as “like Reading, only much farther away” — remains aloof and insouciant. Even his putdowns are muted.

On meeting with the Mongolian prince of Dzun, he opines that the grassland royal ought “to be a romantic figure, a true-blue, boot-and-saddle, hawk-on-wrist scion of the house of Chinghis Khan, with flashing eyes and a proud, distant manner and a habit of getting silhouetted on skylines. But God, not Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, made the Prince.”

Ultimately, News From Tartary will appeal to the armchair traveller unimpressed by the over-saturated colours and opinions of Instagram and influencers, and nostalgic for the subtler era of the gentleman explorer.

Though Fleming married the actress Celia “Brief Encounter” Johnson, served in Greece and India during World War II, was awarded an OBE and many believe was Ian’s model for 007, he described himself as “the brother to which nothing ever happens”. ◉

This is the original, slightly longer version of a review that ran in The Times in December 2020.

SHARE