The first instalment in a two-part story recounts how, in the years after the 1975 fall of Saigon, tens of thousands of persecuted refugees fled their country by sea. And how one ship came to symbolise their long and perilous journey.

“IN OFFICE AT 07.45 and then at 09.30 it all started: Skyluck cut her anchor chain and drifting. The proverbial hit the fan and we were off.”

June 29, 1979, panned out to be a “day of high drama” for Talbot Bashall, who had recently been appointed controller of the Hong Kong government’s new Refugee Control Centre. He recorded its chaos in his diary.

Bashall’s unenviable task was to oversee the arrival, processing and care of tens of thousands of desperate Vietnamese who, having taken to the high seas, had fled their country to seek refuge in the British colony on the southern coast of China. The Skyluck was a 3,500-tonne, Panamanian-registered freighter. Its cargo on this day was 2,600 men, women and children, just a small cross section of the mass migration of refugees from Indochina that the global media had dubbed “the boat people”.

The Skyluck had stolen into Hong Kong on February 7, more than more than 20 weeks earlier. Authorities in the territory had refused to let the refugees land, however, effectively keeping them prisoner on the overcrowded ship.

With the Skyluck’s engines immobilised (Hong Kong Marine Police having removed the ship’s fuel pumps), the 105-metre vessel and its frustrated passengers had been anchored in the West Lamma Channel, between the outlying islands of Lamma and Cheung Chau, for months.

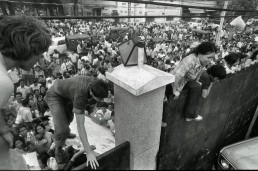

Finally, believing they had been abandoned by Hong Kong and the international community, and in a do-or-die move arising from utter despair, the refugees had severed the Skyluck’s anchor chains with a storm approaching. And now, under a bruised sky, buffeted by strong winds and pushed and pulled by fierce currents, the colossal ship was loose and out of control.

Police launches and salvage tugs were rushed to the scene, scrambling to get lines to the stricken vessel, but their crews were pelted from the Skyluck with bottles, cans and flaming Molotov cocktails. At the top of the ship’s gangplank, one refugee waved an axe to keep cops at bay.

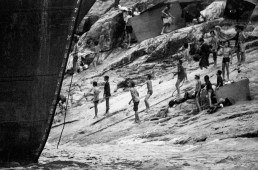

Less than two hours later, the Skyluck’s portside flank smashed into rocks at the north-western tip of Lamma island, where, at the mercy of heavy swells and grinding on bare granite, it began taking in water. While the younger and fitter refugees shimmied down rope ladders and cargo nets to run for the hills, many of the elderly and very young waited on board or huddled by the water’s edge — tired, forlorn and wretched in the rain.

The Skyluck’s journey had come to an end. Those of its passengers had just begun.

FOUR DECADES LATER and I am in San Jose, a Silicon Valley city on the southern edge of San Francisco Bay, in northern California. San Jose has a population of one million, with 10 per cent and 7 per cent respectively claiming Vietnamese or Chinese heritage. (San Jose, in fact, is believed to have the largest Vietnamese population of any city outside of Vietnam.)

Signs at the bus station are in English, Spanish and Vietnamese. My Mercedes-piloting Uber driver is Vietnamese. He drops me at a shiny shopping-and-dining complex called Vietnam Town, where I have a lunch appointment at a Chinese seafood restaurant that, with its circular tables, bright lighting and cacophony of loud voices, could be in Sheung Wan or Shenzhen.

A convoy of cars (including many more Mercedes) makes circuits of the car park. Flags waved from windows are either the stars and stripes of the United States, or yellow with three horizontal red stripes — the standard that was once that of South Vietnam. Protesting modern Vietnam’s larger and increasingly assertive neighbour’s claim to the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, banners and placards read, “China Get Out of Vietnam Waters Now!”

Five members of a Chinese-Vietnamese family have invited me to join them in a private room at the restaurant, to recall their epic voyage to Hong Kong and how that journey was the springboard to new lives in America’s “Golden State”.

Andy Tran, his brother Bryan Chan and sister JoAnn Pham, and their cousins Bill Quach and Richard Quach, were all aboard the Skyluck when it slammed into Lamma, along with 12 other members of their extended clan. Andy and Bill live in San Jose, with the others scattered across the Bay Area.

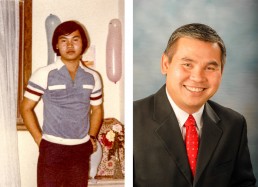

“Everyone had grown so tired, they would take any risk,” Andy Tran, now aged 60 (and 20 when he fled his homeland in 1979), says of the day he finally made contact with Hong Kong soil. “Once the chain was cut, the Skyluck started drifting. At first, the Hong Kong police didn’t know what was going on. They shouted, ‘Don’t panic, we will throw you a rope and pull you back out.’ Then everyone went, ‘Ha ha ha, not a chance.’ When they threw the rope up, we threw it back.”

Taking risks was by now second nature to those aboard the Skyluck. Many had sacrificed everything — settled lives, houses and possessions, family members they might never see again — in their all-or-nothing quest to escape their homeland, and find new homes.

ON APRIL 30, 1975, with the fall of Saigon, the capital city of South Vietnam, to the communist North, the South Vietnamese government collapsed, bringing an end of the long Vietnam War. The following year, Saigon would be renamed Ho Chi Minh City, in honour of the North’s late revolutionary leader.

With the country soon to be officially unified under the Communist Party of Vietnam, bloody revenge against the people of the South (which many had predicted and feared) was not forthcoming. Once the dust of conflict had settled, however, as many as 300,000 people, especially those associated with the southern government and military, were sent to re-education camps to be “reformed” through hard labour and political indoctrination.

A further million, mostly city dwellers, were dispatched to New Economic Zones, essentially primitive agricultural communes where — if they were to survive — they needed to clear malaria-infested jungle and try to grow crops. In 1976, French journalist Jean Lacouture described one zone he visited as “a place one comes to only if the alternative to it would be death”.

Such treatment, as well as growing economic hardship and food shortages, resulted in the persecuted taking to the high seas — often in clapped-out fishing junks entirely unsuited for long-distance journeys — hoping to find sanctuary in Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia. Many would not survive the passage, succumbing to storms and shipwreck, murderous pirate attacks, boat breakdowns and starvation.

The numbers of boat people were initially small. By the end of 1975, some 3,900 had arrived in Hong Kong to be accommodated in hastily prepared camps. The government observed a “first asylum” policy whereby the British colony provided shelter to refugees if Hong Kong was their first port of call, and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) sent representatives to the city to assist.

With the volume of arrivals being low, refugees were quickly resettled overseas, most notably to the US.

By 1978, however, the trickle had become a flood (at its most extreme, in 1979, more than the total number of refugees that arrived in Hong Kong in 1975 landed in the city in a single day). This was largely due to the forced socialist remoulding of industry and harassment of Vietnam’s ethnically Chinese population, who had historically dominated commerce, especially in the South. In March 1978, “all trade and business operations of bourgeois tradesmen” were abolished in Vietnam, and tens of thousands of private enterprises were shut down.

Adding further to the perfect storm, tensions were rising on the Vietnam-China border through 1978, eventually resulting in China’s invasion the following year. Vietnam was increasingly viewing it’s ethnic Chinese as potential fifth columnists and a threat to national security.

FIFTH-GENERATION MEMBERS of an ethnically Chinese family in Vietnam, my San Jose dining companions had lived in a Chinese neighbourhood in Saigon. Andy Tran describes the family as being upper middle-class at the time. They spoke Cantonese and sometimes Fujianese with family, friends and neighbours, and Vietnamese at school, where they also learned Mandarin. “My family sold materials — copper, steel, iron bars — to the construction industry. [Cousin] Bill’s father was working in coffee distribution and retail.”

Their businesses, however, were forced to close.

The group’s escape from Vietnam began in mid January of 1979, when they trekked to the languid riverside town of Bến Tre in the Mekong Delta area of southern Vietnam, about 80km south of Ho Chi Minh City. In the delta, the mighty Mekong river, having meandered 4,300km from the Tibetan Plateau, empties into the South China Sea.

Initially, in the years immediately after 1975, authorities would try to stop all Vietnamese fleeing the country by boat. By late 1978, however, regime officials were accepting under-the-counter payments to look the other way, and soon the cash-strapped government not only encouraged the migration — wanting the Chinese-Vietnamese gone — but also recognised an opportunity for profit.

When the North’s tanks had rolled into Saigon in 1975, many Chinese-Vietnamese had hidden their wealth, often in the form of 24k gold bars or leaves. Now, Vietnamese authorities — notably the Cong An, the Public Security Bureau, effectively the police — in collusion with shady international syndicates, racketeers and unscrupulous foreign ship crews, would facilitate their evacuation, charging for their departure and snatching their homes and worldly goods into the bargain.

“The communists figured out, ‘If we let them go, they’ll pay us and we can take their houses. What a deal!’” says Andy Tran. “The benefit of paying the government was that you would not be caught and sent back. They would let you go.” And the downside? “You’d have to give them everything you left behind.”

Despite denials by Vietnamese officials, all evidence pointed to state-sanctioned people smuggling on a monumental scale.

“My grandmother gave everyone a small gold ring to wear, pure gold, so if we became separated, each of us would have something we could sell”

Skyluck survivor Andy Tran

According to accounts of refugees who spoke to Post Magazine for this story (individuals named here, as well as others who chose to remain anonymous), an adult would be charged, on average, 10 to 12 taels of 24k gold for space on an escape ship (one tael being 1.2 troy ounces); the fee for children was lower and dependent on age.

The price of gold in January 1979 hovered at about US$240 an ounce, so an adult would have been paying approximately US$3,000, the equivalent today of more than US$10,000.

After a few days of waiting nervously in Bến Tre, the family group of 17 was summoned on a date believed to have been January 19, 1979, and boarded a wooden fishing boat taking refugees out to sea.

“We didn’t take much; a little emergency food like instant noodles, because we thought out there we would have nothing, and cans would be too heavy, so easiest would be some crackers and dried food like noodles,” Andy Tran says. “We thought we might not have hot water, but at least you can chew on them. Possessions? Only what we could hand-carry.”

Each person in the group also carried what Tran describes as “self-survival necessities” for emergencies. “My grandmother gave everyone a small gold ring to wear, pure gold, so if we became separated, each of us would have something we could sell. We also carried some US dollars, though not a lot.”

The group did not know where they were heading, only that they were leaving. “We’d just been told we would get out,” says Andy Tran. “The journey was not to anywhere, but to somewhere. Once out, we’d be on our own.”

Having headed out to sea, within hours their small craft was swallowed up by the shadow of an immense ship called the Kylu, its name daubed in large, white letters on the bow and stern of a rust-streaked hull, its deck dominated by a tangle of cargo cranes. Loading took days, says Tran.

Finally, on Wednesday, January 24, 1979, the Kylu — now crammed with some 3,200 refugees — set sail into the unknown.

EXACTLY ONE WEEK after our lunch in San Jose, it is a blue-sky winter’s day in Washington DC, on the opposite side of the United States. Descending into a funky basement coffee shop (its website describes “a Cultural Salon; an Intellectual Sanctuary”), I find myself taking the stairs immediately behind Quan Tran and his son, Thuan “Tom” Tran, the very people I have arranged to meet.

The coffee shop is in the Adams Morgan area of the US capital, a culturally diverse neighbourhood celebrated for its lively nightlife and dining scene. While 42-year-old Tom (close buzz cut; jeans; purple hoodie) lives nearby, Tran senior, who is now 71, resides in the town of Silver Spring, in the state of Maryland, immediately to the north. His olive-green knitted hat matches his quilted North Face jacket, he smiles readily and his short but thick dark hair is only slightly flecked with grey, belying his years.

Quan Tran carries the manuscript of a book he has written, in Vietnamese, “for my family”. It is about their epic voyage to Hong Kong and entitled Thiên Vận, a literal translation of “Sky Luck”, though Tom later explains that more accurate English rendering of the Vietnamese might be “divine destiny” or “heavenly fate”.

“We were the defeated side. I knew at that time that my children would have no future; they would never get to high school. So I thought we had better get out of the country, to find a better life for my children”

Skyluck refugee Quan Tran

In Vietnam, Quan Tran’s family lived between central Saigon and Cholon, the latter originally being a community, located about 10km west of Saigon proper, established by Chinese immigrants to Vietnam in the 18th century. Cholon was recognised as a city in its own right in the 19th century and has long since been absorbed into the urban sprawl that is Ho Chi Minh City today.

Quan Tran’s parents ran a restaurant and he had been an instructor at Saigon’s mechanical engineering school before being drafted into in the South Vietnamese army for two years of the war, serving as a lieutenant. With the South’s collapse, he was sent to a re-education camp, but laboured there, he says, for less than five months because his teaching skills were needed.

Once back at the engineering school, however, Quan Tran could see just how much life had changed for the people of the South. “We were the defeated side,” he says. “I knew at that time that my children would have no future; they would never get to high school. So I thought we had better get out of the country, to find a better life for my children.”

Like Andy Tran in San Jose, Quan Tran left Vietnam in a large group, this time of 15. They included his wife (who, like Tran himself, was 30 at the time) and their two children (daughter Thao, then aged four, and Tom, only days away from his second birthday), as well as three sisters, one brother, three cousins and four more-distant relatives.

Also like the Californians, their departure point would be Bến Tre, where Quan Tran was introduced to the owner of the fishing boat that would be his family’s means of escape. The man needed a mechanic and by taking the role, Quan Tran would not need to pay to get out, handing over only six ounces of gold for his wife, and three ounces for each of his children. “My sisters and cousins paid 12 ounces of gold each,” he says.

As the day to leave drew closer, those waiting in Bến Tre learned of how large ships, which would be significantly safer on the seas than rotting, overloaded fishing boats, had been used by other escapees. Most notable would have been a 4,000-tonne freighter called the Huey Fong that had left the Mekong Delta on December 18, 1978, carrying some 3,300 refugees.

The Huey Fong’s intended first port of call was Kaohsiung, in Taiwan, and so was initially refused entry to Hong Kong. The ship had been intercepted by Hong Kong Marine Police off the Po Toi islands (5km southeast of Hong Kong Island), but was finally received on January 19, 1979, news that was reported on radio stations such as BBC’s World Service and Voice of America.

“We asked the police if we could go in a similar way to the Huey Fong and the police said maybe,” says Quan Tran. “They didn’t promise, but then they said they had a big ship for us. They said there was one condition: if they transferred us to the ship, we would have to give them our boat, so that they could sell it. That was the agreement between us and the police.”

Quan Tran says his fishing boat, carrying what he estimates to have been 120 to 150 people, was one of the first to reach the Kylu. “We were waiting, waiting, and they keep loading people on, back and forth, back and forth. I think it took three or four days before the captain said, okay, enough, and took us away.”

SIXTEEN-YEAR-OLD MAI Tran and his sister Thu-Hong, aged 14, were also aboard the Kylu when it set sail.

The siblings’ father had been a South Vietnam diplomat, stationed in the late 1960s and early 70s at the embassy in Bangkok — the family living in the Thai capital — before returning to Vietnam in 1972 to work in government in Saigon. With the end of the war, Tran’s father and uncles were sent to re-education camps. Tran’s mother eventually bribed an official to have her husband released.

The couple had six children — four girls and two boys — and, says Mai Tran, they tried to escape from Vietnam as a family five times from 1976, but were always caught, his elder sisters being punished with spells in prison. By 1979, a decision had been made: the family would split up for future attempts. Mai Tran and Thu-Hong would go first.

Having learned of how Chinese-Vietnamese were being permitted to escape from the country, Mai Tran’s parents took the two children to the Mekong Delta.

“From Saigon, we went to my mother’s hometown, Bến Tre, where we were met by the local official. They put us into police housing while we waited,” Mai Tran, 55, says by telephone from his home in Fort Collins, in the US state of Colorado. “From there, they took us to Bình Đại, which is the town near the ocean, where we got on the boat. We waited there a week.”

“On our boat — a small, wooden fishing boat — there were 200 to 300 people. It took maybe two or three hours before we could see the ship. Getting aboard was really dangerous — we had to climb up these nets that hung down”

Skyluck refugee Mai Tran

Mai Tran’s parents paid 15 ounces for each child and gave him a 24k gold wedding band that could be sold in an emergency. “We had small bags with just two or three sets of clothes,” Mai Tran says, adding that they also had no idea where they would be heading. “We only knew that we were getting out.”

Mai Tran says he and his sister left Bình Đại early one morning. “On our boat — a small, wooden fishing boat — there were 200 to 300 people. It took maybe two or three hours before we could see the ship. Getting aboard was really dangerous — we had to climb up these nets that hung down.”

Once aboard, the youngsters had to fend for themselves. “We settled in. No cabins, just out in hallways; no beds, just anywhere where you can sit or lay down. For two, three days or more, more people were coming, coming, coming.”

Soon the deck was a chaos of makeshift tents and tarpaulin shelters. Below deck, the ship had three main cargo-storage areas, each split into upper and lower holds. The higher levels filled up first — the dank, dingy bowels still containing some cargo in the form of huge rolls of paper.

“There was a space between the first and second floors, about a metre-high,” says Mai Tran. “There were about six other kids without parents, and that’s where we went, and we would sleep between the paper rolls. Nobody else wanted to be in there — it was dark — so we stayed separate from the main population. They called us ‘the paper kids’.”

QUAN TRAN, IN WASHINGTON DC, says the Kylu’s captain had told him the ship would steer for Hong Kong, to the northeast, but once on the move, he realised this could not be the case. “Each day, I went up to the control cabin to see where the ship was going. I know that at first they go south, but I don’t know where. One day, we saw offshore drilling [possibly for oil or gas], so we thought maybe we were close to Malaysia or Thailand.”

The arrangement that Quan Tran and others had made was simply to get out of Vietnam, hopefully to reach a refugee camp or perhaps to be picked up at sea by a friendly naval vessel, and to be resettled in another country. Where they would land first was not important.

“We took an old oil container, a 55-gallon drum, cut it in half, cleaned it with salt water, and cooked in that. That’s why we ate rice soup with a diesel smell”

Quan Tran

What quickly became the most pressing issue was food. Quan Tran says he initially recalls sandwiches and crackers being provided, but they ran out after just a couple of days.

“There were 3,000 people and they did not have enough food for us, so we had to organise cooking rice soup, but there was nothing in which to cook it. I remember we took an old oil container, a 55-gallon drum, cut it in half, cleaned it with salt water, and cooked in that. That’s why we ate rice soup with a diesel smell. The ration was a cup of rice soup for each person, two times a day.”

For Andy Tran’s sister JoAnn Pham, who was 13 while on the ship and now aged 53, the rice soup was so unappetising it seared into her child’s brain, where it remains as an unpleasant memory. “The worst thing I remember is the porridge cooked in a barrel. Yeuch! You could taste the metal. It was water and just a little rice, and all these other …” — she scrunches her face in disgust — “bits.”

Mai Tran has no recollection of sandwiches, and remembers even more meagre rations. “The food was rice soup, once a day,” he says. “There was no fixed time, it just came when it was your turn. That’s all we had for five to six days.”

The food shortage occurred, the refugees believe, because there were far more people on the ship than had been planned. Though it is true that large numbers of ethnically Chinese were fleeing Vietnam, and large ships and freighters were laid on by people smugglers for those willing to pay to escape, many on board were effectively stowaways, or had been forced aboard, and a large proportion were not Chinese at all.

While the Tran and Quach families, now living in California, are of Chinese ethnicity, only one grandfather of Maryland-based Quan Tran was Chinese, and he considers himself fully Vietnamese. Mai Tran claims no Chinese ancestry at all, which may account for why his parents paid over the odds: 15 ounces of gold for his journey, and 15 for that of his sister, considerably more than most other children.

Years later, after being reunited with his parents, Mai Tran would learn more about the deal they struck to get him out of the country. “According to my mom, they only anticipated 600 to 800 people who paid, but in the end there were 3,000 people. Almost the whole of the village at Bình Đại, they knew what was happening and they used [the ship] as a way to get out as well. Those people were Vietnamese and they got on for free.”

“[The authorities] hired a lot of locals to transport us, and some of them saw an opportunity,” says Andy Tran. “When they transported us, they also came aboard.” The result, he adds, was that many paying customers were stranded in Bến Tre when shuttle boats failed to return from the Kylu. “[Years later] I happened to run into one who … didn’t get on because his fishing boat never came back to pick him up. His taxi never came.”

And, according to Quan Tran, there were Chinese-Vietnamese on board who had not intended to escape at all. “Lots of people in Bến Tre were forced out of their homes in the night because they were Chinese,” he says, adding that while they would not have paid a fee, the Cong An would have snatched their homes and belongings.

Remembering the Skyluck. Video: SCMP/YouTube

IN THE CLOSING days of January, the Kylu entered waters of the western Philippines and verdant tropical islands hove into view. On the evening of January 31, the ship cautiously edged closer to one island and dropped anchor. Soon, refugees were queuing on the freighter’s deck, to descend the gangway to water level to be ferried ashore under cover of darkness.

Mai Tran says he and his sister held back — he saw a chance to assuage their gnawing hunger. “I said to my sister and some other kids, why don’t we just stay back and try and find some food first.” The youngster’s went to where the rice soup was prepared each day and found the barrel in which it was boiled. “We scraped out the burned rice at the bottom to eat.”

Mai Tran was also anxious about leaving the ship’s protection in darkness. “We couldn’t see anything. I said let’s wait until morning, so our group, us kids, that’s what we agreed to do.”

Mai Tran’s caution would result in “the paper kids” being stuck at sea for five more months.

Come the half-light of the approaching day, more than 600 refugees had been offloaded from the Kylu when the mission was hastily abandoned. “It was maybe 5am. My family and I were close to the ladder — I saw the transfer boat that took people from the ship,” says Quan Tran. “Then I heard shots and I saw a flare, and the ship’s crew said the Philippines’ navy was firing on us and we had to get away.”

Andy Tran’s account is similar. “Around dawn, a fishing boat saw us and maybe reported us to the coastguard, so the Philippines navy come out to see what is going on, and we pulled anchor and sailed out of there.”

Meanwhile, in Hong Kong, some 1,400km to the north, 3,274 taels of gold (close to 4,000 troy ounces, then worth almost US$1 million), had been found secreted in a disused oil tank on the Huey Fong, to be confiscated and held at the Treasury. The discovery would have a profound impact on the fate of the refugees chased away from Philippines.

“They parked another ship next to ours and transferred the gold over, guarded by sailors with M16s. They said, ‘Don’t cross this line. This is the open sea, anything can happen here. Cross this line and you’ll be shot'”

Andy Tran

Four decades after the event, what came next for the Kylu is disputed. Though many survivors of the journey are adamant about events they witnessed — and when those events occurred — their personal recollections (like many news reports from the period), while having similarities, are frequently inconsistent.

The accounts of Andy Tran and Quan Tran (who, as far as they are aware, have never met) are alike in many respects. Both claim that, soon after fleeing the island in the Philippines, which would likely have been on February 1, they rendezvoused at sea with another large freighter. Although they had been told the encounter was to be resupplied with provisions, Andy Tran says he witnessed gold being removed from their ship, while Quan Tran suspects this to have been the case.

“The captain said we would meet another ship that would give us food,” says Quan Tran, adding that supplies were shuttled over in a lifeboat, and everyone gathered on one side of the ship to watch. “Meanwhile, they took another boat to the other side [of the Kylu], with the stairs. I went to that side and saw some people. They were not like us; they had nice clothing, not like refugees. I don’t know if they transferred the gold. They had guns. I saw two people with rifles.”

“They parked another ship next to ours and transferred the gold over, guarded by sailors with M16s,” says Andy Tran. “They said, ‘Don’t cross this line. This is the open sea, anything can happen here. Cross this line and you’ll be shot.’ We saw them carry the gold across, and carry food back for us.”

Frank Tran, late brother of Andy Tran, Bryan Chan and JoAnn Pham, and who was 17 at the time, kept a journal about the family’s escape from Vietnam. Later — while being treated for the cancer that took his life in 2011, at the age of 49 — he created a website about their journey (skyluck1979.com). That website also suggests meeting a ship soon after being chased away from the island in the Philippines.

And another US-based refugee from the ship who spoke to Post Magazine recalled heavy bags being taken away on that day, while “men with M16s ensured we stayed at a distance”.

Other accounts of the journey, however, suggest they were met at sea by a freighter in the days or the day before the attempted offloading of refugees. For his part, Mai Tran says he recalls meeting two ships, each on a different day. “On the way from Vietnam to the Philippines, there was a ship that stopped, and people said they took the gold,” he says. “Then, when we left the Philippines, there was another ship that swung by and dropped off food.”

ALTHOUGH THE SHIP had its own captain — from Taiwan — and crew, the refugees had largely been left to their own devices while at sea, and a loose organisational hierarchy had evolved out of necessity, primarily to oversee food distribution.

While some refugees were accorded positions of responsibility because of their Mandarin-language skills (to liaise with the captain), leadership roles were mostly taken by men, in their 20s or early 30s, who had served with the South Vietnam armed forces. Quan Tran was among them.

The refugee leaders demanded the captain tell them of his next move, and they were told Hong Kong was now their goal. Quan Tran claims, however, that the following day (February 2) the ship was again heading south and in the wrong direction. With the refugees angered and unwilling to accept any more delays, Tran describes what happened next as “a little bit of a takeover”.

“When the captain saw that we were a big group, he did not yell at us like he had [earlier in the journey]. He asked what we wanted. We said he had not kept his promise, so we wanted to take over the ship and go to Hong Kong.”

Tran says the captain partially agreed to their demands, but argued that the ship must, for appearances’ sake, remain under his control lest the refugees be open to accusations of piracy, and they accepted this compromise. “After that, I saw a telegram [to the captain], agreeing that we could go to Hong Kong. The message, Quan Tran alleges, also ordered the captain to have the ship’s name repainted.

In short order, crew added the letters S, C and K to the ship’s hull, and the freighter reverted back to its real name. The Kylu, of course, had always been the Skyluck in disguise. And now, loaded with the remaining 2,600 or so refugees, it was steaming towards Hong Kong.

IT WAS NOT THE first time that the long-serving freighter had plied the oceans under a different name to the Skyluck.

While being constructed by Henry Robb Ltd, a substantial Scottish shipbuilding concern at Leith Docks in the Scottish capital of Edinburgh, the vessel was called the Kurutai. Delivered in 1951 to the Union Steam Ship Company in New Zealand, the vessel was then given the name Waimate.

In 1972, the Waimate was restyled Eastern Planet by its new owner, Manila-based Eastern Shipping Lines, and five years later it was purchased by Hong Kong-owned Skyluck Steamship Company and rebranded once more. Soon the name Skyluck would be notorious throughout Hong Kong, the ship commanding front pages of the city’s newspapers and prime slots on the evening news.

“As soon as the anchor was down, I remember everybody came up and went to one side to look, and the ship started tipping. We could see all the lights. It was beautiful”

Mai Tran

In the early hours of February 7, 1979, the Skyluck — as reported by the South China Morning Post the following day — “ignored signals from Waglan Lighthouse” on Waglan Island, one of the Po Toi islands, and quietly slipped into Victoria Harbour, anchoring off the southwest of the Kowloon peninsula, not far from Ocean Terminal.

“We had been living all over the ship — in the cargo hold, all over the deck — but as we approached Hong Kong we were told to throw all the tents from the deck overboard and hide away in the hold,” says Andy Tran. The idea was not to look like “a floating refugee camp”, he adds. “We quietly entered Victoria Harbour at night-time, at about 1am or 2am.”

“Everyone had been told to get inside so we just looked like any other commercial ship,” says Mai Tran. “As soon as the anchor was down, I remember everybody came up and went to one side to look, and the ship started tipping. We could see all the lights. It was beautiful.”

According to the Post’s account of the Skyluck’s arrival, marine police boarded the ship after reports of disturbances on board, to discover human cargo numbering in the thousands and the captain, “to their surprise, tied up and guarded by several refugees” in the wheelhouse. That, insists Quan Tran, was true but not the full story: the captain, he claims, was only tied up once in Hong Kong, and he had agreed to that action in advance.

After initial disagreement from refugee leaders, it was accepted that the Skyluck needed to be moved out of the busy harbour and to a quieter location. This was done at about 2.30pm on the day of the ship’s arrival, the Skyluck escorted to Ha Mei Wan, on the western side of Lamma Island (essentially the part of the West Lamma Channel lying off Hung Shing Yeh and what today is called Power Station Beach — Lamma Power Station only being built in 1982).

Information quickly obtained from Singapore revealed that the Skyluck had sailed from the Lion City at about 8am on January 12. As well as its captain, it held 25 crew (10 from Taiwan, 10 from Indonesia, four from Hong Kong and one from Vietnam), no other passengers and a partial load of paper, corrugated boxes and plywood. With Hong Kong listed as its first port of call, the journey from Singapore would normally take about five days for a ship like the Skyluck.

So where had it been for 27 days?

The captain initially claimed multiple breakdowns at sea, and that his freighter had rescued the refugees from sinking or unseaworthy boats it had encountered between January 18 and 21. His unruly new passengers, he alleged, had seized his logbook and radio log, throwing those records of the journey overboard.

Officers of Hong Kong Marine Department and police were deeply sceptical, however, and an investigation was initiated.

IN COMING WEEKS it was ascertained that, on leaving Singapore, the Skyluck had, in fact, sailed for the southern tip of Vietnam, anchoring off the coast of the Mekong Delta. During the journey from Singapore, the letters S, C and K had been removed from the ship’s name, the goal being to create confusion if the vessel was noticed to be acting suspiciously and reported to any authorities during its illicit mission. (Chemists from the Forensic Science Division of the Hong Kong police examined paint samples taken from the ship, confirming the hiding and repainting of those letters.)

The island in the Philippines where the ship offloaded more than 600 refugees was Boayan Island, off the northwest coast of Palawan Island, in Palawan province. The 1,327-hectare island was largely forested and barely inhabited (as it so remains, with fewer than 1,000 residents, most involved in fishing).

Sheltered by fisherman until rounded up by the Philippines military, the offloaded refugees were transferred to a refugee camp in the city of Puerto Princesa, on Palawan Island, and an Associated Press dispatch released weeks later — in March 1979 — centred around an account, smuggled out of that camp.

Allegedly written by Pham Dang Bao, 30-year-old son of late South Vietnam foreign minister Pham Dang Lam (and one of the refugees dropped off in the Philippines), the account said that gold had been transferred from the Skyluck — “shifted in two sacks” — on January 26, before he left the ship.

The suggestion that a hoard of gold was taken away before the Philippines is supported in the writings of veteran Australian journalist Bruce Grant, drawing on the accounts of Southeast Asia correspondents from Australian newspaper The Age and published in late 1979 as a book (long since out of print) called The Boat People.

In his account, Grant posited that the Skyluck had left Singapore at much the same time as a Taiwan-owned vessel called the United Faith.

“A few days [after leaving Vietnam] she met the United Faith near Indonesia’s Natunas Islands in the South China Sea,” Grant wrote. “The gold was transferred to the United Faith, which was there ostensibly to supply the refugee carrier with food and water. The Skyluck, rechristened the Kylu by the simple trick of painting out the first and last two letters of its name, then sailed north-east towards Palawan.

“The United Faith then made a beeline for Hong Kong where she was met, in international waters, by a fishing boat which offloaded the gold and ferried it undetected in the British territory. ‘A few days later, we saw Vietnamese gold popping up in the local market, but no refugees,’ a Hong Kong official said.”

Indonesia’s Natuna archipelago consist of 272 islands in the south of the South China Sea, off the northwest coast of Borneo, which would tie in with Quan Tran’s assertion that the ship headed south from the Mekong Delta, and that he saw offshore drilling rigs (the area has substantial natural gas reserves, discovered in the early 1970s).

In 1985, however, a Skyluck survivor — by then resettled in New Zealand — told the Post that that gold had been transferred to a “pure white” ship they met off the Philippines one day before the attempt to offload refugees.

“They knew they could not carry the gold with them because it would also be confiscated, so they had another ship park next to it, and offloaded the gold”

Andy Tran

Andy Tran argues that, if the attempt to offload all of the refugees in the Philippines had been a success, there would have been no need to remove illicit valuables from the ship, which again suggests that its booty would have been removed later rather than earlier. “If they had been successful in dropping us off on some island, and we reported to local government how we had been picked up by a ship called Kylu, then they would search for Kylu,” he says. “No one would ever have known that Skyluck had been involved, and they would have gone to Hong Kong as the Skyluck.”

With that strategy thwarted, Andy Tran believes, Hong Kong became the people smugglers’ plan B, but there was a problem. “They knew they could not carry the gold with them because it would also be confiscated, so they had another ship park next to it, and offloaded the gold.”

Another US-based survivor of the voyage tells Post Magazine, “I remember absolutely” that the handover occurred after the Philippines. “[The ships] were moored together side by side, and I saw a man throwing things back and forth between the two boats.”

And on February 24, 1979, the South China Morning Post reported that cryptic ship-to-shore communications, sent as the freighter approached the city, had been traced back by police. One such message — “Pick up auntie” — was believed to have been a request to have something removed from Skyluck.

Whatever the truth, and whether the ship had ever carried a small fortune in 24k gold bars or not, it was now gone. But with the Skyluck’s arrival in Hong Kong — coming so soon after the refugee and riches-laden Huey Fong — the growing fear was that highly organised people smuggling was underway, and of a magnitude that the tiny territory on the southern coast of China would never be able to handle.

With more massive ships crammed with refugees reported to be just over the horizon, the nervous city braced itself for a fully fledged oceanic exodus from Vietnam, and a humanitarian crisis that would stretch Hong Kong’s security forces — as well as its people’s capacity for compassion — to their limits. ◉

Go to Chapter II: Prison Break

With Hong Kong refusing to allow the Skyluck to land, 2,600 men, women and children are kept prisoner at sea. As weeks turn into months, life on board becomes increasingly unbearable, resulting in a high-risk break for freedom.

This feature ran over two consecutive Sundays in Post Magazine in April 2019. Download the entire story as a PDF.

SHARE