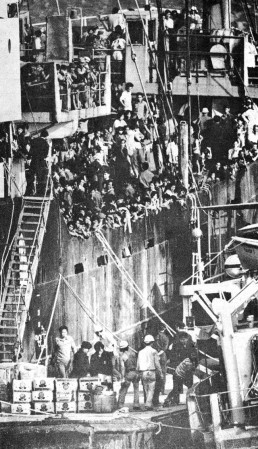

The 3,500-tonne freighter Skyluck arrived in Hong Kong in February 1979 with a cargo of 2,600 Vietnamese 'boat people', who were then forbidden from coming ashore. The second instalment in a two-part story recalls the months the refugees endured as prisoners on the ship, and how they finally escaped to start new lives.

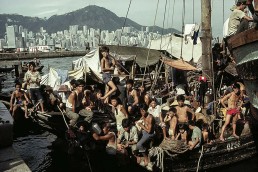

THE STORY SO FAR … With the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, the Vietnam War came to an end and the Southeast Asian country was unified under the Communist Party of Vietnam. Subsequent economic hardship and the threat of forced labour in re-education camps resulted in increasing numbers of people fleeing the country, risking shipwreck, drowning, starvation and pirate attacks by taking to the South China Sea in overcrowded fishing boats.

By 1978, the initial trickle of “boat people” had become a flood, largely due to the Vietnam regime’s persecution of its ethnic-Chinese population — and desire to profit from their wealth by charging the equivalent of US$10,000 today in gold for passage out of the country.

Colluding with international syndicates, Vietnamese authorities were now complicit in people smuggling on a massive scale, with colossal freighters sometimes employed to make the exodus as economically efficient as possible.

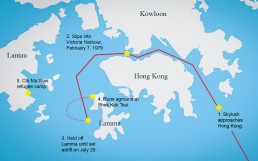

One such ship was a rusting, 3,500-tonne vessel called the Skyluck, which set sail from the Mekong Delta in January 1979 crammed with thousands of refugees. After an attempt to offload its human cargo in the Philippines had been thwarted, the angry passengers demanded that the captain take them to Hong Kong. The Skyluck slipped quietly into Victoria Harbour in the early hours of February 7, 1979.

Part I of the Skyluck story can be found here.

BY THE TIME the Skyluck had arrived in Hong Kong, its cargo of more than 2,600 refugees had been at sea for two weeks, surviving on little more than watery rice soup and hope. Getting food and medical care to them was a priority, and doctors were despatched to what the South China Morning Post newspaper described as the “battered and shabby” ship now moored in the West Lamma Channel between Hong Kong’s outlying islands of Lamma and Cheung Chau.

Soon, the refugees on board had decorated the 105-metre-long Skyluck with signs, banners and painted messages proclaiming, “Life is precious, but freedom is more valuable”; “SOS. Please help us refugees from Vietnam. Thanks a lot”; “We are extremely hungry, but we need freedom more”; and “Food and Medicine save refugee lives”.

A pontoon was lashed to the ship to facilitate food delivery. Supplies were chiefly canned and included sardines, pork luncheon meat, baked beans and condensed milk, as well as oranges, dry crackers and sliced bread. By the end of the day after the Skyluck’s arrival, some 2.4 tonnes of provisions had been reported as delivered (by February 12, total supplies would top 13 tonnes and be estimated to be costing Hong Kong HK$5 — then about US$1 — per refugee per day).

After that initial burst of activity, provisions were delivered to the pontoon every two days, to be distributed by the refugees themselves. Skyluck passenger Mai Tran, now aged 55, speaking from his home in Fort Collins, in the US state of Colorado, remembers a typical share: “Four people share a can of beans, four people share a can of ham, four share a can of condensed milk, two people share an orange, two or three pieces of bread per person, some crackers …”

The Skyluck passengers expected to be held on the ship for some days: it was standard procedure for boat people arriving in Hong Kong to be kept at anchorage for a week, effectively quarantined at sea. Due to the ship having entered the harbour illegally and covertly, thereby embarrassing those charged with keeping track of such arrivals (the approach of the refugee-crammed Huey Fong had been closely monitored), the refugees were informed, on February 9, that they would not be allowed to land any time soon.

While day-to-day essentials would continue to be delivered, and their medical needs met, the Skyluck would be guarded around the clock by at least one police launch. And so began a standoff that would last for the best part of five months — until, in late June, the frustrated refugees, their tempers fraying and patience stretched, would take matters into their own hands in the most swashbuckling fashion.

‘IT WAS A TERRIBLE life,” Quan Tran, a 71-year-old survivor of the Skyluck’s journey who eventually resettled in Maryland, says of their months held in maritime purgatory, adding that for months he, his wife and their four-year-old daughter and two-year-old son would be squeezed into an area “like a king bed; it was so small”.

An instructor at Saigon’s mechanical engineering school before being drafted into in the South Vietnamese army for two years of the Vietnam war, serving as a lieutenant, Quan Tran had been sent to a re-education camp after the fall of Saigon, but laboured there for less than five months because his teaching skills were needed. Married with a four-year-old daughter and one-year-old son, he chose to escape Vietnam to provide a better future for his family.

“We were like a big sardine can, with each one of us a sardine,” he says of life on board the Skyluck.

One highlight in each day was what Mai Tran — who was 16 while on the Skyluck, and travelling with his 14-year-old sister (his parents and four other siblings were to escape from Vietnam later) — describes as “a kind of flea market” that sprang up on the deck of the ship, testament to the Vietnamese and Chinese instincts for commercial enterprise, both of which had been repressed under the totalitarian regime at home.

“A system of pricing was established — for one can of milk, pay maybe half a loaf of bread — because currency doesn’t mean anything on the ship”

Skyluck survivor Andy Tran, on how a barter economy functioned on the ship

“After we landed in Hong Kong, the food supply was pretty good. Bread, canned beans, milk, but some families would not need milk while kids would need more milk, so we started exchanging food,” recalls Andy Tran, now aged 60 (and 20 when he fled his homeland in 1979). Andy Tran resettled in San Jose, in California’s Silicon Valley, with siblings and cousins also making new lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

“‘Hey, I’ll give you my bread. How about you give me your milk.’ A system of pricing was established — for one can of milk, pay maybe half a loaf of bread — because currency doesn’t mean anything on the ship.”

“It was quite good compared to what we had been used to,” Quan Tran says of the food provided, “but eat one thing over again and you get sick of it. For many years after, I could not eat beans or luncheon meat or sardines. I was sick of them.”

“After a while we asked for freshly prepared food, and then they would bring it three times a week,” adds Quan Tran, who, having been in the South Vietnam military, soon found himself among the de facto refugee leadership on the Skyluck. “But the food was not enough for the young people. Older people, we were okay, but the young people, especially if alone, they did not know how to save food.

“When they got it, they would eat it in one day, and the next day they would be hungry.”

Asked today what she remembers most about the months marooned off Hong Kong’s Lamma island, Andy Tran’s sister JoAnn Pham, who was 13 while on the ship, and now aged 53, laughs and says, “Hungry, hungry, hungry, hungry, hungry.”

From February 19, cooked rice and some hot food were provided. Later, in April, it would be increased to two hot meals a day.

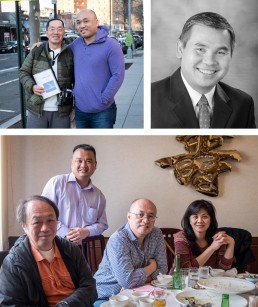

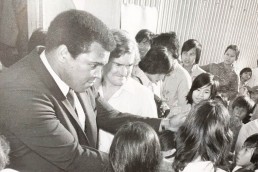

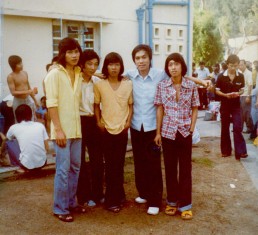

Clockwise from top left: Skyluck survivors Quan Tran and his son, Thuan 'Tom' Tran, in Washington DC; Mai Tran, who is now based in Colorado; and California-based siblings Andy Tran, Bryan Chan and JoAnn Pham (seated, from left), and their cousin Bill Quach (standing). Photos: Gary Jones and courtesy Mai Tran

WHILE THE SKYLUCK was guarded to ensure refugees did not abscond, police presence also kept journalists and the simply curious away from the ship. This lack of communication with the outside world led to a belief among refugees that they were being deliberately pushed from the headlines.

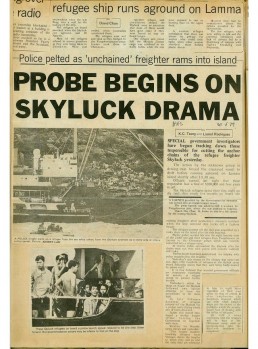

Indeed, updates from the Skyluck all but disappeared from the Post after February 20, with stories focusing instead on the daily arrival of other refugee boats, and into the slow-moving investigation into the ship’s journey to Hong Kong, with its Taiwanese captain and pan-Asian crew facing charges for involvement in a people-smuggling racket.

All that changed on March 11, more than a month after the Skyluck’s arrival, when, starting from early morning, new signs began to appear on the ship. Messages read: “We plead for freedom not isolation”; “Don’t let us be forgotten. Let us land!”; “Run for life. Run for freedom”; “Have pity on us. Let us land please!”; and, “Help us land as soon as possible”.

Then, at about 10am, 100 or so young male refugees began leaping overboard to swim the 1,500 or so metres to shore, some using tin containers — in which foodstuffs had been delivered — as improvised flotation devices. Half of the swimmers were quickly picked up by police launches, but about 50 reached Lamma’s Hung Shing Yeh beach, most to be quickly rounded up and taken to the nearby police post, where two were treated for exhaustion. Through the post’s chain-link fence, others handed pre-prepared written pleas to land to journalists.

One 15-year-old swimmer was at liberty for 12 hours, smuggled off Lamma on a public ferry by a group of European picnickers, taken to a Mong Kok hotel where he was briefly reunited with his 17-year-old sister, possibly from an earlier refugee boat, and was even interviewed on local TV before turning himself in.

Mai Tran was one of the volunteer swimmers, but quickly realised he was out of his depth, in more ways than one. “I swam a bit, but it was so cold that I turned back,” he says. “It was lucky I did. I don’t think I could have handled it.”

“We just wanted the public to know we were there and not be forgotten. We know we cannot escape. How can we escape?” says Quan Tran.

“We’d been there, isolated, for more than a month. We wanted our families to know where we were, and that we were safe. We cannot do this while stuck on the ship, so we decided to try and get inland, to tell people, to tell the press, that we were there. If people in Vietnam listened to [radio stations like] the BBC or VOA, they would know that we had got to Hong Kong. That’s all we wanted.”

When the Hong Kong representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Angelo Rasanayagam, sent a letter to the Post, decrying the lack of press coverage of the Skyluck refugees’ plight, veteran Vietnam war photographer and Hong Kong-based journalist Derek Maitland used the newspaper’s pages to slam what he called a “total information blackout on refugees” by the government that had “denied the public any personal contact with these people and effectively reduced them to dehumanised newspaper statistics”.

AFTER THE SWIMMING action, the Skyluck was hauled further from Lamma’s shore (“We thought they were going to pull us in, but they pulled us out,” recalls Andy Tran) and a police launch was moored to the pontoon alongside the ship. An air of despondency settled over the refugees, who struggled to fill their days.

Music lover Andy Tran had books of music theory in the minimal possessions he had brought from home, which he studied. “I like to read but there wasn’t much reading material,” he says. “There was a reverend [on the ship] and so I also read the Bible three or four times, to kill the days. Some of us would gather on the deck, just sit around and talk, watch the sunrise or sunset.”

His sister JoAnn Pham “read the labels on [food] cans, over and over and over again”. Their cousin Bill Quach, who was just nine years old then, and 49 today, says the months “felt like years”.

Teenager Mai Tran struggled with a feeling of helplessness. “Just the waiting, not knowing what was going to happen, seeing no light at the end of the tunnel,” he says. “We had no contact with our family at all for about six months. Hunger we could manage, and we would exercise by jumping in the ocean and swimming against the current. We had friends so we could socialise, but not knowing about our family, not knowing our future, those were the hardest things.”

“There were 2,600 people there, and we had 2,600 heads with lice”

Refugee Quan Tran

When the Skyluck had arrived in Hong Kong in February, doctors found that just three people were suffering from only minor ailments: two men and a four-year-old boy, who were taken to hospital to be treated, and then returned to the ship. In the months that followed, there were cases of pneumonia, internal bleeding, skin conditions, tuberculosis, sciatica, diarrhoea, haemorrhoids, measles and mumps, and even a suspected instance of leprosy.

With two very young children to watch over, Quan Tran was tormented by the thought that disease could spread quickly on the ship. “We were lucky that it didn’t happen but I was very scared about that,” he says, adding that there were a number of doctors among the refugees. They would cater to everyday complaints, with medications provided by Hong Kong authorities.

“People who got badly sick, or who were pregnant or needed some special care, would be transferred to hospital,” says Quan Tran. “They were lucky because they got lots of food, lots of meat. Some people wanted to get sick.”

While the ship’s deck was usually awash with young men, the elderly, women and children tended to stay inside the holds, where — with so many unwashed bodies in close quarters — the air was stale and nauseating, permeated with the stench of diesel, grease, rust, sweat and worse.

Maintaining hygiene was a struggle, Quan Tran remembers, especially as months dragged on and the mercury soared. “We had only two litres of water for each person a day, so could not have a proper wash. We had to save it to have a proper shower,” he says. “There were 2,600 people there, and we had 2,600 heads with lice. I think there were three people who did not have lice, because my friend shaved his head and shaved his daughters’ heads.”

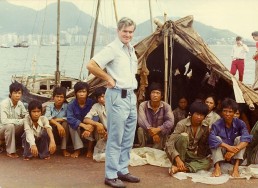

ON APRIL 18, 1979, 52-year-old Talbot Bashall was appointed controller of the Hong Kong government’s new Refugee Control Centre, headquartered at Victoria Barracks, then in Admiralty (and roughly where Hong Kong Park and the Pacific Place shopping mall sit today). The Skyluck had by now been isolated off Lamma for the best part of 10 weeks.

Born in the English county of Surrey, Bashall had served with the British Army in Italy and Palestine in years that followed the Second World War. He arrived in Hong Kong in 1953, carving out a career in correctional services. Starting out as an officer in Stanley Prison, he later ran a prison-staff training school and an institution for young offenders. None of this, however, had prepared him for the life-changing challenge that lie ahead.

“People tend to think of the boat people as coming in smaller vessels, and that had been the case in previous years. Everything changed from late 1978; this was industrial scale,” says Bashall, speaking by telephone from his home in suburban Perth, in Western Australia, where the 92-year-old lives in retirement.

With boats streaming across the South China Sea, sometimes arriving in the dozens every day, Bashall and his team struggled to feed, process and provide shelter for tens of thousands of men, women and children, all the while liaising and negotiating with the UNHCR and foreign consulates in the hope of finding countries willing to take them in.

Bashall’s diary entry for May 11, 1979, reads: “The storm hit me as the magnitude of the influx became evident. Boats queuing up to get in choking up the approaches. Really a horrific situation”. And on May 21 he wrote: “HK is really being clobbered these days, and daily they are coming in.”

On May 26, a decaying freighter — smaller than the Skyluck, at 800 tonnes — carrying more than 1,400 refugees had entered Hong Kong. The captain and crew of the Sen On (really the Seng Cheong, with the painted name on its hull changed) had jumped ship somewhere near Macau for a fishing junk, advising former members of the South Vietnamese military among their human cargo to steer for the bright lights of Hong Kong. The refugees were advised not to engage with Hong Kong authorities and immediately to beach the vessel, which they did, on Lantau island, then to be transferred to refugee camps.

Despite denials from Vietnam, it was now widely accepted that the communist government there, supported by smuggling gangs, was encouraging the exodus of Chinese-Vietnamese citizens, exploiting their financial resources and trading in human misery.

On June 7, Hong Kong’s information secretary David Ford estimated that Vietnam would earn US$3 billion through the on-going expulsion of refugees. “We know that the Vietnamese government regards this trade in human lives as a major source of foreign exchange,” Ford said. “Indeed, it is now said to have overtaken their largest export earner, their coal industry.”

Five days later, in a lengthy dispatch from Hong Kong headlined “Hanoi Regime Reported Resolved To Oust Nearly All Ethnic Chinese”, The New York Times stated: “Vietnam appears determined to expel virtually all the members of its ethnic Chinese minority and is exacting hundreds of millions of dollars from them before their departure.”

The report continued: “To encourage the Chinese to depart, they have been subjected to harassment, including loss of jobs, closure of schools, curfews, intimidation by the police and the creation of detention camps.”

ON JUNE 13, refugee leaders on the Skyluck refused to collect food delivered to the pontoon tied beside the ship. “The police kept promising, saying we could land soon,” says Quan Tran. “We lost patience, so we tried a hunger strike.”

Bashall was dismayed by what he regarded as a lack of gratitude, writing on June 13: “Skyluck refugees on hunger strike […] What a liberty. All uninvited and making demands!”

The following day, Bashall continued: “Two letters, petitions, appeared on my desk [from the Skyluck]. One pleading and the other uglier. Refusing food and saying they will starve to death. With the hardening mood of the [Hong Kong] people and Government I suspect they will get short shrift.”

Indeed, the Hong Kong public was turning against those washing up on its shores from Vietnam, mainly due to their sheer numbers but also because the territory was paying for their upkeep. “The best way to describe the situation in Hong Kong was that we suffered from compassion fatigue,” Bashall says. “It was a deluge.”

On top of that, many felt that there was an unjust double standard at play: those fleeing Vietnam were permitted to stay, while mainland Chinese furtively entering Hong Kong from neighbouring Guangdong province were being hastily repatriated. In the first three months of 1979 alone, more than 8,000 illegal immigrants from mainland China were apprehended in Hong Kong. Though many of those people would have had family in the colony, they were sent back across the border.

On June 18, after five days, the Skyluck began accepting food once more. The hunger strike had failed — Hong Kong authorities had not budged, even though the refugees had stressed that their patience was now stretched to breaking point.

Believing they had been abandoned by Hong Kong and the international community, and with a lesson having been learned from the deliberate beaching of a freighter on Lantau in May, drastic action, it seemed, was needed if the increasingly restive refugees were ever going to get ashore. On the night of June 28, they took it.

“AFTER THE HUNGER strike, we thought there was nothing more we could do, so that’s when they decided to cut the anchor chains,” says Quan Tran. The refugee leaders, he adds, approached the beaching of the Skyluck like a military campaign.

Young male volunteers were organised into teams, each with strict orders. There was a team for cutting the chains and a security detail to protect the cutters from other refugees (in case there was physical opposition to the action). A group was charged with repelling police once the Skyluck was free of its moorings, and a team would oversee evacuation of the ship in case of any accident.

According to Quan Tran, a heavy-duty hacksaw and 10 blades were obtained from one of the ship’s crew, and there were about 10 refugees in the cutting team, working in shifts and pairs (one man wielding the hacksaw, one pouring water to cool the blade). “I think we started cutting at about 7pm, and [it took] until about four or five in the morning to cut both chains.”

Before they were severed, the anchor chains were secured with ropes, so the ship would remain fastened, if temporarily, to the seabed. Cut the ropes and the Skyluck would be free in an instant. The job had taken longer than expected, however, and by the time the cutting team was done, the tide was going out rather than in. The refugees would bide their time.

By about 9am on June 29, however, baleful clouds were gathering. “I could see the sky getting dark and that a storm was coming,” says Quan Tran. “One of my friends, who had been a navy officer, looked at the sky and said that in 10 minutes the storm would arrive. I went back to the group and told them we should cut the rope in 10 minutes. And that’s what we did.”

“Not everyone knew about cutting the anchors,” says Andy Tran. “They didn’t want to announce it properly because of leaks. We were not involved but we heard about it. They were worried that if the police found out, they’d never be able to pull it off.”

“The tugboats tried to get in and push us out, and so Molotov cocktails were thrown around them, to protect the ship”

Quan Tran

Quan Tran says that when frantic police realised what was happening, they “put the sirens on and tried to stop us”.

Though it was expected that the Skyluck would be pushed into Lamma, initially the ship drifted outward and towards Cheung Chau island as police reinforcements rushed to the scene. “There were many more police boats and they got two tugboats out,” says Quan Tran. “The tugboats tried to get in and push us out, and so Molotov cocktails were thrown around them, to protect the ship.”

“I was up top. I was 16, not afraid of anything. It was exciting, things were happening, ‘I’m going in,’” recalls Mai Tran, who has no recollection of a storm or even whether it was raining, “I remember it as a nice day,” he adds, amused by the thought. “It was a good day for me. I was taking the next step: to get off that ship.”

“They were very well prepared with gasoline bombs: they used baby-food bottles filled with fuel from the ship’s tank,” Andy Tran says of those protecting the Skyluck. “They started throwing them at the police boats, so the police kept their distance.”

Eventually, compelled by strong currents, the Skyluck looped eastward and back towards Lamma, its portside flank colliding with the rocky headland at Shek Kok Tsui, north of Yung Shue Wan village. “The plan was to damage the ship once it had hit the shore, so that tugboats could not pull us back out to sea again,” says Quan Tran. “But when the ship hit, I went down to the machine room and I heard the mechanics say that water was coming in, so we didn’t have to.”

Cargo nets and ropes were thrown down the side of the ship, with many of the younger men, caught up in the excitement of the moment, made for land, some running for the hills. But quickly they realised there was nowhere to go, and were rounded up by police and reinforcements from the British army, who had arrived on the island in numbers via landing craft and helicopters.

During the course of the day, the refugees were shuttled on boats from Yung Shue Wan on Lamma to a temporary detention centre — formerly an open prison — on Lantau island’s Chi Ma Wan peninsula.

That evening, Hong Kong’s secretary for security Lewis Davies gave a press conference. “Some persons on board either sawed through or slipped the anchor cables,” he said. “This was an irresponsible action since it placed those on board in considerable peril in the weather conditions then prevailing. The ship also posed a potential threat to other shipping.”

Under the Shipping and Port Control Ordinance at the time, anyone who scuttled or beached a ship in Hong Kong could be jailed for up to four years and fined HK$200,000 (about US$40,000). In their barracks-like accommodation at Chi Ma Wan, Quan Tran and his friends kept their heads down.

On June 30, with the refugees all safely ensconced on Lantau, Bashall wrote in his diary: “Thank goodness Skyluck is out of the way! What a relief!” The following day, he appeared less stressed than usual in his diary entry, and almost to be enjoying his demanding role. “Towing of boats from DBA [Discovery Bay Anchorage, used as a refugee holding area] to Dockyard the main item today but with Skyluck drama, over who cares! Nice to be in the thick of things.”

Speaking today from his retirement in Perth, Western Australia, Bashall says that while he does not condone the refugees’ action, it did remove what had been a major headache. “When they cut that anchor chain, in a whisper I can tell you they did us a favour because they solved the problem which had been the bane of my life,” he says. “I knew they had to come ashore sooner or later, and this resolved everything.”

BASHALL’S RELIEF IN seeing the Skyluck refugees finally housed in a refugee detention centre begs the question, why had they not been allowed to land for so long?

A plan to get them ashore was well underway, says Bashall, and the facility at Chi Ma Wan was all but ready for their arrival when the ship ran aground. “Amazingly enough, I arranged an exit plan for the people on the Skyluck — I must have been psychic — 24 hours before they cut the anchor chain,” he says.

This claim is backed up by Bashall’s diary, the entry for June 23 stating, “Next week contingency plans for Skyluck are to be finalised.” His entry for June 27, the day before the anchor chains were attacked, reads, “I then photocopied the Skyluck evacuation plan. Meeting followed on this plan.”

According to Bashall, the refugees were kept in floating limbo simply because there was no space for them. “Every time we were preparing to relocate them, other batches of refugees arrived and we had to put it on hold. Refugees were pouring into Hong Kong, 1,000 a day at that time, and we were overwhelmed. In fact, on one day [June 10, 1979], 4,516 arrived in a 24-hour period.”

Those on board the Skyluck complained that other refugees who arrived after them had been allowed to land. When their ship had entered Victoria Harbour on February 7, the territory was already accommodating 10,360 refugees, according to a Post report. During the months the Skyluck was kept at sea, almost 50,000 more were brought ashore.

“I saw a lot of small boats and other ships pass by, and when they got to Hong Kong they were landing,” says Quan Tran of their months of maritime purgatory. “Only we were kept on the sea.”

Supporting this, a Post editorial of March 24 claimed that, not including those aboard the Skyluck, “there are now 15,792 refugees here”. And Bashall’s diary entry for May 2 states that “a staggering 978 refugees poured [in] with a grand total of 23,801. It was a hectic day as they all are these days, with Skyluck hovering always, as we know that the 2,661 [sic] have got to be brought ashore sooner or later. At the moment there’s simply no space for them.”

The diary entry for May 11 reads: “Over 25,000 refugees here now.” May 21: “A long day with over 30,000 in Hong Kong, and 9,000 odd in dockyard.” June 1: “Over 41,000 in Hong Kong now.” June 10: “We approach the 50,000 mark with great rapidity”. June 21: “We now top the 51,000 mark.”

On June 30, the day after the Skyluck was beached on Lamma, the Post reported that Hong Kong camps were home to 58,667 Vietnamese refugees.

Bashall argues that many small boats were barely seaworthy on arrival and so they took priority. He recalls the case of the Ha Lung, which arrived on April 15 (just days before he took on his role with the Refugee Control Centre). As a rule, such smaller vessels carrying refugees were first kept at anchorage, before being towed to a government dockyard transit centre at Yau Ma Tei, for processing and health checks, therefore effectively quarantined at sea for a week.

The 35-metre Ha Lung carried 571 people — more than 200 being children — in what Bashall describes as “deplorable” conditions. “They were jammed in,” he says. “‘Sardine ship’ was the term used by the South China Morning Post. I went on that particular boat and don’t know how I found room to stand. It was packed to the gunnels; men, women and children in the most ghastly situation you can imagine.”

Bashall had the Ha Lung fast-tracked and towed in by April 20.

“We didn’t turn a single boat away during my posting, and I was there for three and a half years, day in and day out … I am very, very proud of that fact”

Talbot Bashall, controller of Hong Kong’s Refugee Control Centre, 1979-1982

Those confined on the Skyluck were and remain sceptical of such reasoning, partly due to a rumour that spread aboard the ship: Hong Kong authorities, it was said, were looking for the gold paid by the refugees for their journey. “In the first week and second week, they came every day to search for gold,” says Quan Tran. “They brought divers and kept diving around the ship.”

Police had told Quan Tran that they had found about 4,000 ounces of gold — then worth close to US$1 million — hidden on the Huey Fong, a massive freighter carrying some 3,200 refugees that had arrived in Hong Kong from Vietnam just weeks before the Skyluck.

“They searched all the sailors’ cabins, of course, and captain’s quarters,” says Andy Tran of the Skyluck. “They did not find anything. They suspected that they might have hidden it underneath the Skyluck, so they even had divers. We saw them jump in off the police ship to search underneath. Obviously, they suspected we had gold, but they couldn’t find any, so they kept us there.”

And while those fleeing Vietnam in the years immediately after 1975 were soon accepted as legitimate refugees and resettled in other countries, most notably the US, their increasing numbers from 1978 onward resulted in reluctance to take in refugees from Hong Kong. In May 1979, 18,688 boat people arrived in the city, while only about 500 left Hong Kong camps to be resettled in other countries; in June, 19,651 arrived and just 1,600 or so departed for new lives overseas.

ACCORDING TO THE UNHCR, by mid-1979 there were 350,000 refugees in camps across the region, with tiny Hong Kong holding a disproportionately large share. At this point, the countries of Southeast Asia announced that they would not accept new arrivals and would even push boats back out to sea. Hong Kong did not join them.

“We didn’t turn a single boat away during my posting,” Bashall says, “and I was there for three and a half years, day in and day out … I am very, very proud of that fact. There were one or two voices in Hong Kong who suggested that perhaps we turn the odd boat away, but I wouldn’t have a bar of it. I saw too much misery first hand.”

According to government figures, Hong Kong took in 68,784 boat people in 1979 alone.

Today, four decades later, Bashall is still angered by the ruthless stance of some regional leaders of the time, saying he has “nothing but scorn” for Malaysia’s current Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, who was deputy prime minister in 1979. Bashall recalls an article that ran in the Post (on June 15, 1979).

The report stated: “Malaysia announced today that it would ship immediately more than 70,000 Vietnamese refugees in camps in Malaysia back into international waters and shoot on sight any boatpeople entering Malaysian waters. ‘If they try sinking their boats, they will not be rescued, they will drown,’ Deputy Prime Minister, Datuk Mahathir Mohamad, said. ‘Their drowning will be because they sank their own boats, not anything else.’”

Following a meeting convened by the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, in July 1979, however, Vietnam agreed to institute an Orderly Departure Program that would smooth the way for those wishing to immigrate to other countries, and Western nations committed to accelerate resettlement. Though the worst of the crisis was over, boat people would continue to leave Vietnam for more than another decade.

By the early 1990s, Hong Kong had taken in more than 230,000 and would only close its last refugee camp in June 2000. In total, the boat people crisis cost the city HK$8.7 billion. To this day, the UNHCR owes the territory in excess of HK$1.1 billion for what the government describes as “outstanding advances”.

IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE Skyluck ran aground on Lamma, its crew was taken into custody. The captain and five sailors were eventually charged with conspiring to defraud the Hong Kong government by making false representation as to the circumstances in which the passengers boarded the Skyluck. In January 1980, they were acquitted of all charges.

Though the captain and crew members had elected not to give evidence in court, their defence had argued that proof of conspiracy existed only in the context of a plot to take the refugees to the Philippines, not to Hong Kong, and that the captain had been forced by the refugees to enter the colony under duress. The judge said he believed the defendants to be “evil” men who trafficked in human cargo, but that the evidence before him was insufficient to support the charges.

Also immediately after the beaching, 12 refugees were taken into custody. Subsequently, 10 of them, males ranging in age from 18 to 34, were charged with rioting, four to be convicted.

Law Chang, 24, was sentenced for two years imprisonment for throwing Molotov cocktails at police launches, while Lac Thanh, 22, who wielded an axe to keep police from boarding the ship, received two and a half years. Two other refugees, identified by police for throwing bottles and cans, were each sentenced to a year. The sentences of Lac and Law were later reduced by six months on appeal.

With Chi Ma Wan being only a temporary solution for passengers from the Skyluck, within weeks they were moved to more-established refugees camps, with many heading to the Jubilee Transit Centre in Sham Shui Po, which was an open camp — run in collaboration with the UNHCR — that refugees were permitted to leave to find paying work in the community (from July 2, 1982, to deter further arrivals, the Hong Kong government introduced a closed-camp policy, with refugees effectively imprisoned like criminals).

Mai Tran found employment at a company making sweaters, inspecting garments for faults and being paid HK$5 (US$1) a day. Later, he increased his income with a job injecting plastic into moulds to make leaves for fake flowers, for HK$15 a day. Quan Tran found work in a watch factory, making metal watch-straps, and then in the printing section at a fabric mill.

Andy Tran’s immediate family were also housed in Sham Shui Po, the adults finding work as assemblers of electronic components. They worked for less than a month, however, before they were on a plane heading for California, having been sponsored by a relative who had worked with the US military in Vietnam and left in 1975. “Because we left so quickly, we never got paid for our work,” Andy Tran says, laughing.

IN INVESTIGATING THE story of the Skyluck, and wading through newspaper and magazine cuttings, accounts from boat people and journalists, and TV news footage from the time, the number of refugees aboard the ship while it was in Hong Kong appeared to change with every report. Stories in the Post alone gave figures ranging with the day from 2,600 to 3,000. A total of 2,665 was provided by the Post once the refugees had been rounded up on Lamma, later to be revised to 2,651.

It was, of course, difficult to count so many people while they milled about in the ship’s maze of holds, stairwells and corridors. John D Slimming, the Hong Kong government’s director of information services, suggested another reason for the fluctuating number when, in May 1979, he told the media, “They keep having babies.”

While moored off Lamma, the Skyluck had ceased being a means of transportation and become a functioning community like any other, with all the associated births and deaths, dalliances and dust-ups, and instances of happiness and heartbreak. The first Skyluck birth recorded while the ship was in Hong Kong occurred on February 10, when a 6lb, 11oz baby boy was delivered. There would be a total of 16 newborns before the ship ran aground in June.

On-board deaths were far fewer. According to refugee accounts, the first occurred before arrival in Hong Kong, on January 30, 1979, when a sick baby died as the ship approached the Philippines. The family performed a burial at sea.

When 100 or so refugees had leaped overboard on March 11, to swim to Lamma in an attempt to publicise their plight to the media, one 20-year-old (the Tran family in San Jose remember his name as being Tang On) was later found to have drowned. He was cremated at Cape Collinson, with 30 people from the Skyluck given special permission to attend the Buddhist service.

Bashall also recalls that a woman, aged 78, died while held in limbo off Lamma.

“Her name was Giang Vinh, she was the matriarch of her family,” Bashall says. “I pulled out all the stops to move her body from the Skyluck to the morgue in Kowloon. No easy job — it took a week of to-ing and fro-ing. Her family got in touch, asking if, as a matter of compassion, they could visit her in the morgue to ‘close her eyes’, which I assume is an old Vietnamese custom. I arranged for half a dozen of her family to leave the Skyluck and do that, and then they returned.”

Romances also blossomed on board. “I was 16 years old, so I looked for girls to talk to,” says Andy Tran’s brother Bryan Chan, 56, in California. “I found my wife, now my ex-wife, on the ship. I would talk to different ladies at night, and I found one. That was the best thing about the Skyluck.”

One love affair that began on the Skyluck ended less happily, however: on August 22, 1979, the freighter’s assistant engineer, Nguyen Van Hai, 50, and his 22-year-old refugee lover, Doan Ngoc-can, tied their hands to each other with rope and threw themselves from the top deck of the Cheung Chau ferry in a suicide pact. Their bodies were found the next day.

A note in Doan’s pocket revealed how the pair had met on the Skyluck and they had become close while the ship was held in Hong Kong. At the time of their deaths, Doan was an inmate at Chi Ma Wan; Nguyen — who was already married — was on bail alongside other crew charged for transporting the refugees to the city.

IN EARLY 2019, although the windswept tip of the headland at Shek Kok Tsui on Lamma, where the Skyluck ran aground, looks much the same today as it did in 1979, old photographs reveal the land has become significantly more forested in the intervening 40 years, and getting there today requires worming through densely packed trees and clothes-snagging brambles, following faint trails used by weekend fishermen.

Having been seized by authorities but abandoned for months on Lamma, in December 1979 the ship was sold for scrap, for a reported HK$500,000. With the holes in its hull roughly patched, on May 14, 1980, the battered vessel was towed to a ship-breaking company at Junk Bay, where it was dismantled.

There are no signs at Shek Kok Tsui today that this was where the Skyluck came to the end of its working life, and where the lives 2,651 refugees began anew.

Among the first to head on from Hong Kong were Andy Tran and members of his extended family, who flew to California in September 1979. Today, Andy Tran is a musician and music teacher, his brother Bryan Chan, with a master’s degree in technology management, is engineering director with a vehicle-fleet tracking company, while their sister JoAnn Pham, a graduate in business marketing, forged her career in customer service and product control.

Their cousin Richard Quach was 17 when they left Vietnam. Having obtained his degree in civil engineering in the US, he has worked in that field and as a respiratory therapist. Richard’s brother Bill Quach graduated in electrical engineering, and is pursuing a master’s in psychology while working as director of security with a technology company.

The five have eight children between them, variously studying in high school or at university, or employed in fields ranging from retail and credit services to software engineering and biotech research.

Quan Tran and his family reached the US in May 1980. A younger brother sponsored their resettlement. He had fled Vietnam earlier via Thailand, and been sponsored himself by a cousin who worked with the US military during the Vietnam war. Aged 30 and with significant responsibilities, returning to education proved unrealistic for Quan Tran. “I tried to get back to school, to become a professional engineer,” he says, “but I was so busy working to support the family.”

Immediately after arrival in the US, Quan Tran started lessons to improve his English, but had to quit after less than two months. “I needed a job. I got work as a truck mechanic and, with the skills I had, within a couple of months I was promoted to be a trainer. My wife did not work at first because of the children, but two years later, we sponsored our parents to come here, and they could look after them, so my wife trained to become a beautician.”

Quan Tran is now retired. His daughter, Thao, 44, is a doctor — an allergy specialist — in Seattle. His son, Tom, 42, works in IT in Washington DC. Tom has the Chinese character tiān (天) — meaning sky, or the heavens, and which decorated the Skyluck’s funnel — tattooed on his upper arm.

Mai Tran and his sister, meanwhile, made it to the US on January 9, 1980, exactly one year after they had set off from their family home in Vietnam. The entire family was only fully reunited, in the US, in 1990, a full decade later. Mai Tran and his brother went on to build a successful IT company in Colorado, with close to 200 employees, before selling the business in 2009.

CONSIDERING THAT THEY had to give up so much to leave their country, calling the Skyluck survivors fortunate would be less than accurate.

According to the UNHCR, however, while 800,000 people fled Vietnam by boat and made it safely to foreign countries or territories between 1975 and 1995 (with the largest share resettled in the US, and the majority of the rest taken in by Australia, Britain, Canada and France), it has been estimated that a further 200,000 to 400,000 were lost at sea.

And although he accepts that life aboard the Skyluck was no easy ride, and he is grateful for the life afforded to him and other refugees in affluent, easy-going California, Richard Quach says he recalls the months spent trapped on a rusty, overcrowded freighter off Lamma island with perplexing nostalgia.

“I look back on those days, and see that they were perfect days, they were like vacation days; we were really and truly purified, with no burdens,” Quach says. “You can have a nice house and a lot of money, but with that there is a burden, you carry baggage. In those days, we had no baggage. We were free.” ◉

This feature ran over two consecutive Sundays in Post Magazine in April 2019. Part I can be read here. Download the entire story as a PDF. Talbot Bashall passed away in September 2020 at the age of 94. Read his obituary in The Times.

SHARE