China’s urban landscapes are transforming at dizzying speed. The author of a new book explains how female architects are behind some of the country’s most inspiring new architecture.

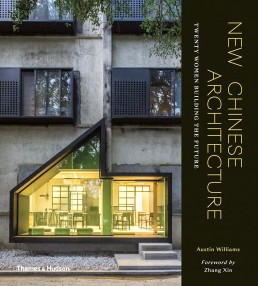

WITH JUST ONE hour to go before the China launch of New Chinese Architecture: Twenty Women Building the Future, the book’s British managing editor, Austin Williams, is explaining why he wanted no mention of females on its cover.

Although the full-colour volume is hailed in its marketing blurb as “the first of its kind detailing the lives, achievements and ambitions of 20 successful, influential women architects living and working in China today”, he would have preferred no gender-revealing spoiler.

“I envisaged this book being called ‘Twenty Chinese Architects’, full stop, because if you saw ‘Twenty Chinese Architects’ as the title, and you opened it up and they were all men, you wouldn’t give it a second thought,” Williams says.

“I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be fun if you then discovered that they were all women.’ That might give you cause for reflection on how women are seen to participate in this industry.”

INVITED TO CHINA in 2011 to help establish the architecture department of Xian Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU) in Suzhou, Williams is an honorary research fellow at that college, as well as a senior lecturer in architecture at London’s Kingston School of Art.

He stresses how timeframes are compressed in fast-changing China, pointing out that the country’s first private architecture practice in the modern era was only opened in the early 1990s. “This is not like the West, with 200 years of playing around with this stuff,” Williams says. “We are talking just 25 or so years.”

One consequence of this squeezing of time is that women are increasingly playing a pivotal role in Chinese architecture, and projects spotlighted in the new volume include everything from rural schools to gargantuan commercial developments in major cities.

Among them are architect Qi Shanshan’s Nine House, an inviting boutique hotel and gallery in the ancient water town of Xitang, just an hour’s drive from downtown Shanghai, in Zhejiang province. Qi is the founder of Studio Qi in her hometown of Hangzhou, also in Zhejiang, and Nine House won an Urban Environment Design Magazine accolade as China’s Most Charming Boutique Villa in 2016.

More monumental assignments detailed in the book include the massive Yinchuan Museum of Contemporary Art in northern China’s Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, by architect Zhang Di of WAA Architects in Beijing. Her swooping, 13,000-square-metre structure sits beside the Yellow River, its shape mimicking surrounding sedimentary rock formations.

Zhang Jinqiu’s solemn Yanan Revolutionary Memorial Hall, meanwhile, is a communist pilgrimage site in the region of Shaanxi province that Mao Zedong made his “Red Capital” from 1935 to 1947. While most women featured in New Chinese Architecture are from the new generation, Zhang — who has worked with China Northwest Architecture, Design and Research Institute for more than 50 years — is now in her 80s.

THE BOOK’S LAUNCH and an accompanying exhibition are being held at Shanghai’s sprawling West Bund Art Centre, housed in a former aircraft factory beside the Huangpu River. The repurposed 10,000-sqm complex now comprises exhibition spaces and galleries, lecture halls and performance facilities.

Although Williams’ name appears on the book’s cover, an all-female team of XJTLU students carried out much of its research and interviews, and some of the fresh-faced youngsters make last-minute adjustments to architectural scale models spread throughout the exhibition space, while wall-mounted profiles describe the career trajectories and design philosophies of the included 20.

It seems only fair, then, that New Chinese Architecture’s publisher insisted on having “women” on the book’s cover, differentiating the slab-like tome on bookshelves. All statistics suggest, after all, that men have historically dominated architecture not only in China but worldwide.

“Today, less than a third of the American Institute of Architects membership is female, and a survey of the world’s 100 largest architecture firms […] found that women occupied just 10 per cent of the highest-ranking jobs”

The New York Times, in 2018

In September of last year, the New York Times noted that “architecture was long viewed as a ‘gentleman’s profession’” and had “systematically excluded women for most of its existence”.

“Before World War II, you could count the number of noted female architects on one hand. As late as the 1990s, the percentage of architecture firms owned by women in the United States was still in the single digits,” the Times continued.

“Today, less than a third of the American Institute of Architects membership is female, and a survey of the world’s 100 largest architecture firms by the online design magazine Dezeen found that women occupied just 10 per cent of the highest-ranking jobs.”

One month earlier, art-industry website Artsy pointed out that in the US “women make up nearly half of the student body in architecture schools, and yet those numbers drop off dramatically in the professional field, where women make up a paltry 18 per cent of licensed architects”.

Today, Williams says that “the situation is changing more quickly in China than in America”, whilst also accepting that deep-seated cultural constraints persist in much of the People’s Republic, particularly in the agricultural hinterland. “There is still pushback from the familial framework: respect for elders, getting married, not being a ‘left-behind woman’ — there is still that social pressure,” he says.

And then there are the time-consuming demands of what is a punishing industry the world over. “Even though [Chinese] employment law is moving in line with the global economy, women have kids and so take time off, so historically it’s unlikely they would have been employed in architecture in the first place,” Williams argues. “There is definitely this thing in architecture: there is no time off. It’s not a nine-to-five job; this is a midnight-to-midnight job.”

TALENTED EXCEPTIONS can break such rules, however, and Williams says Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid greatly inspired the most recent generation of female Chinese practitioners. Zhang Di’s aforementioned Yinchuan Museum of Contemporary Art clearly owes a debt to the “queen of the curve”.

In 2004, Hadid became the first female to win the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest accolade. (Two other women have since won the Pritzker, but only jointly: Japan’s Kazuyo Sejima, in 2010, and Carme Pigem of Spain, in 2017.)

While Hadid’s notable projects include the 2012 London Olympics Aquatics Centre, the National Museum of Arts of the 21st Century in Rome, and the Al Wakrah Stadium in Qatar (an under-construction venue for the 2022 World Cup), China was very much her early 21st-century playground, before she died of a heart attack at the age of 65, in March 2016.

Guangzhou Opera House, Beijing Daxing International Airport, Morpheus hotel at City of Dreams in Macau, and Jockey Club Innovation Tower at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University all bear her unmistakeable stamp.

Despite Hadid’s passing, Williams occasionally refers to her in conversation in the present tense.

“It’s almost the fact that she’s a rarity that gives her more power,” he says, adding that Hadid had agreed to write the foreword to New Chinese Architecture but there was a delay in delivery of her text. “I wasn’t going to pester her. I thought I’d give her another month, she will come back to it. And in that month, you guessed it, she died.”

Hadid’s foreword duties were eventually covered by Zhang Xin, co-founder of mainland developer SOHO China.

Williams also points out that Hadid, in keeping with the spirit of his book, believed that gender plays no practical role in architecture. “She has always argued that she does not want to be viewed as a woman architect but just as a good architect,” he says, “and that is what gave her renown: that she was damned good, even if you didn’t like what she did. She knew what she wanted; she was an authoritative figure.

“This is a tough business and she was a tough businesswoman. She made things happen.”

WILLIAMS SAYS MODERN China’s development path threw up differing societal expectations for men and women, and this can be witnessed in their approaches to building design, or at least in how they rationalise their work.

In New Chinese Architecture, Williams writes: “Until the first decade of the new millennium, engineering was deemed to be a core skill for China’s rapid urbanization and development. After all, until only a few years ago, the Central Politburo of the Communist Party were all engineers, as their aim was to rebuild the nation.

“Recently, China has entered an era of creativity and innovation that requires a softer edge to its skills-based educational provision. Now art, philosophy, history and design-led courses are increasingly becoming a first option for undergraduates.”

The economic reforms of China’s late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, which kicked off in the late 1970s, provided the impetus for the country’s transformation, as Williams writes in his introduction, “from a predominantly rural economy into an urbanized nation faster than any other country in history”.

From the 1970s to the turn of the century, he argues, with men flocking into engineering and nation-building proceeding apace, aesthetic finesse was not the priority. “Stick a shelf on a wall. If it doesn’t fall down, it’s a good shelf,” he says.

Women trickled into the industry in increasing numbers later, largely thanks to the social changes unleashed by Deng’s reforms, and over time traditional constraints loosened. The approach of female architects, Williams’ China experience has taught him, has arguably less emphasis on pragmatic practicality than that of their male counterparts.

The concept of “it’s not the box but the space inside the box that makes the box”, he says, was embraced more by women than by men. “I don’t want to sound like a parody by saying women are more emotional, but they do seem able to explain things in a more nuanced way. They want to get more aesthetic clarity out of their design than the guys, who are a bit more workaday.”

“Due to societal expectations and norms, I am constantly made aware by others that I am a woman working in a field largely occupied by men”

Architect Du Juan

Asked whether she considers herself specifically to be a female architect, Qi Shanshan brushes aside the question. “If any male architect calls himself a ‘male architect’, then I will,” she says, simply. Her description of her Nine House boutique property in Xitang, however, is significantly more florid. Qi speaks of “the movement of space and events” and the “shifting and juxtaposing of volumes, compressing and releasing of moments, intervening or penetrating negative space”.

Du Juan, associate dean of the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Hong Kong, and who heads up IDU Architecture in that city, is also included in New Chinese Architecture. She insists that her personal journey has had a significantly greater impact on her work and philosophy than her gender.

Shandong-born Du has worked extensively in the US, Europe and China as an academic, theoretician and architect. She has taught at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Peking University and other respected institutions. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including at the Venice Architecture Biennale.

“Due to societal expectations and norms, I am constantly made aware by others that I am a woman working in a field largely occupied by men,” Du says. “Being a woman of course shapes how I think and work. However, my gender does not predominately define my sense of aesthetics or approach to architecture, which are cultivated from my bicultural background, multicultural education, as well as professional training in different countries.”

One of Du’s projects highlighted in New Chinese Architecture is Open House, described as a “preservation and adaptive-reuse project of a 1940s four-storey residential building in Hong Kong’s historic Sai Ying Pun area”.

“The Open House was my first project involving Hong Kong’s unique building type — the tong lau, or Chinese walk-ups,” Du says. “We wanted to create an open and modern architecture that demonstrates the possibility of giving a new life and new value to this culturally unique, urban housing type that has been relegated to a relic from Hong Kong’s past by the general public.”

WILLIAMS IS RELUCTANT to single out favourites among the 20 architects in his book but, when pushed, he admits, “I like Dong Mei, if only because of her charming design ideas.”

Dong founded BieChu KongJian Architects in Beijing with her husband, Liu Xiaochuan, in 2004. Their projects include Beijing Badaling Forest Experience Centre (a museum promoting preservation of woodlands) and Ding Xiang Eco-Village, both in the shadow of the Great Wall.

Energy conservation is central to Dong’s approach, with the architect embracing environmental protection — as she explains in New Chinese Architecture — even “before China’s public building energy-efficiency standards came out. We did a lot of theoretical investigation and practical research on how to simplify building volumes, improve natural ventilation, and so on.”

Williams also singles out the “heroic story” of Tang Yuen, the septuagenarian chief architect at the Shanghai Institute of Architectural Design & Research who today oversees more than 1,500 staff. In 1967, China’s Cultural Revolution disrupted Tang’s education just after she had completed her undergraduate studies at Beijing’s Tsinghua University. It would be 11 years before she could resume her studies, this time at Shanghai’s Tongji University.

Tang went on to design a number of notable public buildings in Shanghai in the late 1980s, including the 84,000-sqm Shanghai Library, and contributed to sympathetic restoration of the Peace Hotel. Constructed on Shanghai’s Bund in 1929, the hotel reopened in 2010 and remains one of the city’s most important art deco landmarks.

What most impresses Williams about the works in New Chinese Architecture, however, is their variety, even — or especially — within individual portfolios. For example, the built projects of Wang Wei, founder of the practice Field Architecture Office in Beijing, include the sensitive, modern-meets-regional regeneration of rural Baima village in south-western China’s Sichuan province, and a 200-metre-long, multi-purpose development in Chengdu’s Panchenggang district that encompasses a community centre, a gym, a farmers’ market and a police station.

For Wang, who no longer shies away from being described as a “female architect”, being distinctive overrides any other label.

For the Panchenggang project, she resisted the urge to think vertically, turning the skyscraper concept on its side and building horizontally. The development has echoes of the vast, low-rise factories that once defined the local landscape. “The site is filled with memories from Chengdu’s industrial past,” Wang says. “I wanted to show my respect for that heritage.”

“The variation, the variability, the varied nature of their work is striking,” Williams says of the architects in New Chinese Architecture. “You do not get that in the West, where one will have an oeuvre, as they say: you become a commercial architect, or a hospital architect …”

Williams also calls attention to “intensely private” Lu Wenyu, wife of 2012 Pritzker winner Wang Shu — the first Chinese citizen to win the prize. The couple founded Amateur Architecture Studio in Hangzhou in 1998. The Pritzker jury described its work, which frequently draws on Chinese tradition and uses salvaged materials, as “timeless, deeply rooted in its context, and yet universal”.

Amateur Architecture’s completed projects include Wenzheng Library at Suzhou University, Ningbo Historic Museum and China Academy of Art’s Xiangshan Campus in Hangzhou.

“There’s been a campaign in the West asking why Wang Shu won the Pritzker when his wife was equally involved in the work,” Williams says. “When you chat to her, she doesn’t want it. She says, ‘I like to sit down with my feet up and a cup of tea after a hard day in the office. I don’t want to be flying around the world going to international conferences, so leave me out of it.”

While larger-than-life Hadid certainly qualified as an alpha-careerist “star-chitect”, humble Lu never will, of her own volition. In the pages of New Chinese Architecture, she says: “After Wang Shu won the Pritzker Prize, his private life disappeared, but I wanted mine. I want my life.”

Defying critics who lambasted her for not demanding her share of fame and letting her husband take all the glory, Lu adds, “To assume that I — or anyone — merit acclaim simply by being a woman is wrong.”

“In Chinese architecture, as in Chinese society, the question is, ‘How do you marry the individual with the state?”

Architect Austin Williams

Williams, meanwhile, maintains that the star-chitect phenomenon, now so entrenched in the West, is unlikely to take root in today’s China. “Politically, it can’t. It would not be allowed,” he says, adding, however, that Ma Yansong (founder of Mad Architects, headquartered in Beijing) might perhaps qualify for such celebrity, alongside Wang Shu.

Ma was mentored by Hadid in London, and Williams bundles him creatively with Britain’s Thomas Heatherwick (remember the UK’s “Seed Cathedral” pavilion at the Shanghai Expo 2010?) and Bjarke Ingels of Denmark “in that weird, playful, architectural framework”. (Ma Yansong and Wang Shu are both male, of course.)

According to Williams, Chinese architects, no matter how successful and respected they become, are unlikely ever to be blessed with “the same level of autonomy that they can then do whatever they damn well please because” — in China, at least — “there will be constraints on what they can and cannot say”.

“In Chinese architecture, as in Chinese society, the question is, ‘How do you marry the individual with the state? How do you marry the idea of creating a globalist future with a traditionalist past while safeguarding the stability and harmony of the system?’”

As an example, Williams considers Ma’s Chaoyang Park Plaza complex in Beijing, which echoes the contours of black-granite mountains and reflects on Chinese shanshui paintings. “He’s trying to make some sort of connection [with tradition],” Williams says. “Whether he is saying that to satisfy the paymasters, I don’t know. But people are playing with the fact that they have to be part of the system, and that’s a tricky balance.

“Most of these architects — and I don’t think this is a conscious, cynical process — are genuinely trying to find what is the new Chinese architecture, but to do that you would have to have a social break with the past. If you don’t, you are only going to repeat some of the traditionalist ideas, and you’re going to do pastiche stuff.”

THE INTERNATIONAL LAUNCH of New Chinese Architecture will coincide with the London Festival of Architecture, which is being held at various venues across the British capital through June. The associated exhibition will kick off at the University of Liverpool in London’s campus, in Moorgate, on June 27 and run for three weeks.

With last-minute tweaks being made to the displays in Shanghai, Williams says that while most of the 20 women architects featured in the new book studied abroad, most notably in the US, Chinese architecture is now at a watershed moment. Multiple influences — Chinese, other Asian and Western — are melding, he believes, to create something new, eclectic and dynamic in China.

“That Japanese thing, about doing beautifully crafted buildings in very small, awkward spaces. That taps into the Confucian mindset in China, so people are shifting Asian-wards rather than just replicating some crazy parametric building in San Francisco,” Williams says.

“Then there’s a search for authenticity in terms of Chinese architecture, and that is looking into the realm of the past. But at the same time — because you can’t have a conversation about China without talking about its contradictions — there’s also a generation that is globalist in its mind-set, who are looking to Australian vernacular, to Japanese high-rise, to weird West Coast architecture. People are experimenting.

“We’ve moved away from people going away to be educated in creativity, to coming back to be educated in creativity, and we are right at the moment, at that cusp, when the new direction might be found. These are interesting times.” ◉

This feature ran in Post Magazine in June 2019. Download PDF.

SHARE