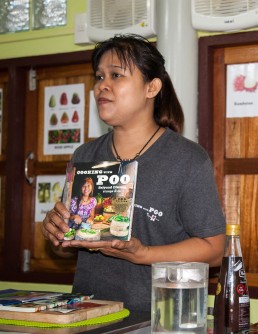

Cooking with Poo

Saiyuud 'Poo' Diwong, a home-taught cook working out of Bangkok's biggest slum, captured hearts with her inspiring story and quirky book of recipes. After a fire threatened to destroy everything, she's back in business with a new cookery school.

IN 2012, THE WORLD’S media gleefully reported that a Thai cookbook — in competition with Estonian Sock Patterns All Around the World and A Century of Sand Dredging in the Bristol Channel — had won an international prize for the oddest book title of the year.

The giggle-inducing Cooking with Poo was the work of Saiyuud Diwong, who is better known by her nickname — which is short for Chompoo, or “rose apple”, in Thai — and a long-time resident of Klong Toey, the largest and most notorious slum in Bangkok.

At the time, Poo had been running an unpretentious cooking school in Klong Toey for only a few years. The result of the book’s triumph — and all the subsequent publicity — was swift.

THOUGH POO’S MODEST operation was already popular, employing slum neighbours and proving a model of positivity in a bleak landscape of poverty and despair, suddenly she was being feted by gastronomy’s great and good.

British celebrity chef Jamie Oliver shared the cover of Cooking With Poo on Instagram and the book became a quirky Christmas stocking-filler worldwide. Media tours of Australia and the UK followed — with Poo energetically knocking up a massaman curry with Oliver for TV cameras — and the curious pounded a beat to ramshackle Klong Toey in increasing numbers. Five-star reviews piled up on TripAdvisor.

Then, in August last year, disaster stuck: a fire started in a nearby home reduced Poo’s immediate neighbourhood to ashes. Her cooking school had gone up in smoke. But you can’t keep a self-proclaimed “superwoman” down — and now, after a rebuild and refit, the unlikely culinary entrepreneur is back in business.

Cooking With Poo: Number Two, anyone?

“Life was hard work — 12 hours a day. I’d start work at 5am every day, no holiday. A lot of people in my area did the same”

Saiyuud ‘Poo’ Diwong

A Cooking with Poo class starts with a tour of Klong Toey’s labyrinthine outdoor market. On the Thursday that I join a class, Noi and Tai, two of Poo’s team of helpers, lead 10 new students through aisles jammed tight with mountains of young coconuts and mangos, overflowing bamboo baskets of holy basil, mint and coriander, writhing catfish and monster eels, decapitated frogs, waxy pig heads and so much more, all at rock-bottom prices.

Grinning ear to ear, Poo is waiting outside her school when we arrive, welcoming us into a single room of perhaps 250 square feet. Walls are painted a pleasing lime green and photos and posters of Thai dishes and beaches decorate the space. The atmosphere is more cash-strapped kindergarten than international school of learning.

Poo remembers life before she opened the school, when she sold food to neighbours from her home in the slum, making just Bt200 (then about US$7) a day. “Life was hard work — 12 hours a day,” she says. “I’d start work at 5am every day, no holiday. A lot of people in my area did the same.”

One of Poo’s regular customers was Anji Barker, an Australian aid worker. When soaring produce prices saw Poo struggle to make a living, Barker suggested she open a cooking school. After an intensive effort to learn English (“Back then I could only say ‘yes, okay, no, thank you’”), Poo managed to rustle up a successful business.

THE “VERY QUICK, very easy” dishes on Poo’s menu lean towards the street-food end of the culinary spectrum, with different dishes made each day of the week. Options include coconut chicken soup, green papaya salad and minced duck with lemongrass. Today we will attack three Thai staples: spicy beef salad, pad thai noodles with prawns, and green chicken curry.

Decked out in aprons emblazoned with the words “I cooked with POO and I liked it”, we get to work on the beef salad, chopping lemongrass, kaffir lime leaves and spring onions just so. Poo strolls among her charges, offering an encouraging thumbs up here and a useful tip or two there. “If you don’t like spicy, slice the chillies bigger,” she advises. “For me, I use five chillies, but for you, maybe just one.”

Poo’s signature recipe of smiles and banter continues through the pad thai (“put the bean sprouts in later if you like crunchy”; “cut the spring onions bigger — nice colour”). She is accustomed to foreign visitors’ preference for a healthier approach than what’s typical in the slum, and she avoids oil, products with colourings (such as the yellow tofu popular in pad thai) and sugar as much as possible. “Thai people loooove sugar,” she says, laughing.

Poo tells her story to Jamie Oliver. Video: Jamie Oliver/YouTube

POO’S HEALTHY APPROACH extends to the green curry, and she rejects ready-made solutions for the from-scratch approach, crushing galangal, lime rind, chilli, lemongrass, garlic and onion into a kryptonite-green paste with a pestle and mortar.

“When I was young and cooking with my mother, I hated the pestle and mortar,” she says, lifting a T-shirt sleeve to flash a meaty bicep. “It was one kilo, so now I have very big muscles. It’s good exercise. Makes a woman a superwoman!”

The four hours of the class rush by and end with most students purchasing the now-famous Cooking with Poo book, and maybe an apron or a T-shirt. And before waving goodbye, Poo shrugs when asked about the fire that nearly tore up her recipe for success.

“The bad luck is gone; the good luck is back,” she says, smiling yet again. “We can have a holiday, we can have a long weekend, plus we are helping others in the slum. We can put money in the bank, and together we have hope and sweet dreams. I’m very proud.” ◉

This story ran in Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post in April 2015. The operation has grown to become Cooking with Poo & Friends. Price and booking via cookingwithpoo.com.

SHARE

Poetry in Motion

As the poet's 100th birthday approaches, a Chinese academic is working to introduce the Welshman's wistful, frequently surreal but always rewarding words to his homeland.

DYLAN THOMAS NEVER visited China during his short life of 39 years. The Welsh poet — much loved for his innovative use of language and intoxicating imagery — did, however, refer to the country in a revised version of his Reminiscences on Childhood, which he read aloud on radio in 1953, the year of his death:

“I was born in a large Welsh town at the beginning of the Great War, an ugly, lovely town — or so it was and is to me — crawling, sprawling by a long and splendid curving shore where truant boys and Sandfield boys and old men from nowhere beachcombed, idled and paddled, watched the dock-bound ships or the ships streaming away into wonder and India, magic and China, countries bright with oranges and loud with lions…”

The “ugly, lovely town” Thomas spoke of on the BBC’s Welsh Region Home Service was Swansea, where the author of haunting poems And Death Shall Have No Dominion and Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night, and the polyphonic “play for voices” Under Milk Wood, was born 100 years ago on October 27.

And now his dream-like musings of a journey to China are scheduled to become an after-life reality.

MULTIPLE EVENTS HAVE been arranged for the centenary of Thomas’s birth, including a 36-hour “Dylathon” of readings of his works at Swansea Grand Theatre, timed to end on the hour of his delivery. The readings will be made by the Prince of Wales, actor Sir Ian McKellen and former Wales rugby captain Ryan Jones, among other notable fans.

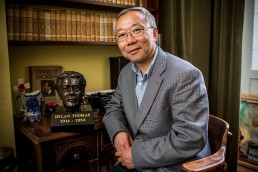

And earlier this year, on a less star-studded but similarly groundbreaking occasion, a low-key academic also visited Swansea — on a mission to produce a definitive guide to the writer’s oeuvre in Chinese. Professor Wu Fu-sheng has now translated 25 key pieces of Thomas’s work. A book is scheduled for release in 2015.

“Personally, I like Dylan Thomas’s handling of the English language and poetic conventions to create his unique style of poetry,” says Wu, 55, who was raised in the northern Chinese city of Tianjin and today is professor of Chinese literature and comparative literary at the University of Utah in the United States.

“I find his description of nature very beautiful, and his pantheistic, poetic vision or representation of life and death — the ‘process poetics’ — very moving.”

“Thomas deliberately challenges and even violates the norms of English language in his poetry, making his poems difficult and obscure even to English readers”

Professor Wu Fu-sheng

Having worked in a textiles factory as a young man before attending Tianjin’s Nankai University, Wu headed to the US in 1990 to obtain his doctorate in literature. Thomas, by contrast, was disinterested in formal studies, leaving school at 16, with much of his poetry appearing in print while he was still a teenager.

Heavy with symbolism and dabbling in surrealism, Thomas’s creations, though refined in craftsmanship, were always tricky to pigeonhole. Wu says they still pose “intriguing issues” for English-Chinese translation.

“Thomas deliberately challenges and even violates the norms of English language in his poetry, making his poems difficult and obscure even to English readers,” he says. “But in poetry, obscurity and uncertainty sometimes can create multiple meanings, which add to the depth of the poems in question. In Dylan Thomas’s poetry, this is particularly true because he loves to use puns.

“Unfortunately, a translator must often choose one possibility out of several, thereby limiting the scope of the poems. Thomas’s poetry exposes in acute ways the limitations of translation.”

WU VISITED THOMAS’S birthplace in Swansea: the humble, semi-detached, red-brick house of the writer’s family at 5 Cwmdonkin Drive, where he lived until he was 19 and wrote many of his finest compositions. There, Wu read aloud, in Mandarin, excerpts from Thomas’s poetry, including Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night, for an invited audience.

“It was really an inspiring experience,” Wu says. “I saw the room where he wrote many of his poems, and his father’s study where he often hid himself as a teenager.”

Wu found his sojourn to the Welsh fishing village of Laugharne, where Thomas, his wife and newborn son lived a hand-to-mouth existence in the late 1930s, especially poignant.

“There, overlooking Thomas’s ‘heron priested shore’,” says Wu, “listening to his recorded reading of Poem on his Birthday, which is one of his last poems, written there, I came to a much better understanding of many of his works, especially Over Sir John’s Hill — also written there, in his ‘writing shed’, by which I found myself fixated for quite some time during my visit — one of my favourites and a moving meditation on the process of life and death.”

Wu has translated Thomas's work into Chinese. Video: Swansea University/YouTube

PROFESSOR JOHN GOODBY, from the department of English at Swansea University and a world authority on Thomas, was instrumental in bringing Wu to Wales.

The recent author of The Poetry of Dylan Thomas: Under the Spelling Wall, Goodby believes Thomas’s work breaks down the barriers between “high” and “popular” art, and describes his manipulation of the English language as “profoundly satisfying, provocative and beautiful”.

“In a world in which politicians, businessmen and administrators are busy trying to reduce language to dead, jargon-ridden discourses, he reminds us that we are all capable of using it for very different ends, or — perhaps best of all — for no end, purely for imaginative play,” Goodby says. “When Thomas begins a poem with, ‘Once below a time’, we think, ‘Yes, why not ‘below’, rather than ‘upon’?’”

“I think there will always be two Dylans: Dylan the great poet and writer — the words on the page — and then Dylan the larger-than-life character who packed so much into his 39 years”

Antiquarian book dealer Jeff Towns

Swansea-based antiquarian book dealer Jeff Towns has spent four decades keeping Thomas’s legacy alive, He even has the closing lines of his poem Fern Hill tattooed on an arm (“a 60th birthday present from my wife,” he says).

The self-styled “The Dylan Thomas Guy”, Towns has personally aided individuals as diverse as Beat Generation poet Allen Ginsberg, illustrator Ralph Steadman and Prince Charles to boost their knowledge of Thomas and his writing.

“Throughout his life, and even more since his tragic early death, he has continued to reverberate with popular culture,” says Towns, citing Thomas’s influence on singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, and how the poet made the cut to appear amongst the montage of faces on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album.

Others famous fans include former US presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, Mick Jagger, Charlie Chaplin and actor Pierce Brosnan (who has a son named Dylan Thomas Brosnan).

IN THE YEARS before his untimely death in 1953, Thomas acquired a reputation — which he encouraged — as a hard-living drunk and hell-raiser. Dying young while on a tour of New York resulted in the creation of a James Dean-like myth around the writer. (The post mortem provided a less glamorous version his death: the primary cause being pneumonia, with pressure on the brain and a fatty liver as contributing factors.)

To this day, while Thomas is celebrated as one of the most accomplished poets of the 20th century, that semi-fictional image of the doomed romantic has often overshadowed his writing.

“I think there will always be two Dylans: Dylan the great poet and writer — the words on the page — and then Dylan the larger-than-life character who packed so much into his 39 years,” says Towns.

Goodby also believes that the cult of Dylan Thomas has had a peculiar but positive effect in keeping his legacy alive. “All of Thomas’s work remains in print because of the legend, and the large general readership means that there is always a chance that some will seek to go beyond the wisecracks and the tales of drunkenness and debauchery,” Goodby says.

Though some of Thomas’s poetry had been translated into Chinese in the past, Wu’s attempts will be accompanied by critical annotations and explanations, offering insights into his life and character, and a more rounded portrayal of the writer. “These features will surely be of great help to the Chinese readers to appreciate this great but difficult poet,” Wu says.

“The legacy of Thomas’s work is complex and profound,” adds Goodby.

“He had a major impact on later English-language poets, and because his poetry deals with the universals of conception, birth, love and death … he has had an impact beyond the Anglophone world, too — in Germany, France, Poland, Argentina, South Korea, West Africa and, hopefully soon, in China.” ◉

This feature ran in Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post in October 2014. Download PDF.

SHARE

Wintour in Beijing

On her first ever visit to China, Vogue's empress of high fashion says it's time for Asia to step out more confidently on the global catwalk. Controversy, however, dogs her latest issue.

ELFIN IN STATURE and instantly recognisable beneath pageboy bob haircut and Willy Wonka sunglasses, Anna Wintour strides towards the Central Academy of Fine Arts’ auditorium on a suitably frosty morning in the Chinese capital Beijing. Her reputation precedes her like a crackling and hostile storm front.

The British-born editor-in-chief of the American edition of Vogue is the most powerful and polarising figure in her industry. She has been slated as demanding, imperious and intimidating; labelled as ruthlessly ambitious and occasionally malicious. Wintour does not suffer fools at all, let alone gladly, according to one former assistant. And “she doesn’t do small talk”.

Inside the auditorium, a full house of Chinese design students has rallied to participate in a rare question-and-answer forum with high-fashion incarnate. They fidget skittishly while the press pack huddles in anticipation of an “Icy Wintour”, of a “Nuclear Wintour” (her distaste for that unflattering sobriquet is on the record). All await the headline scribbler’s mother lode.

NINETY MINUTES LATER and the dispersing congregation is nonplussed. Was Meryl Streep’s Cruella deVille-like fashion editor-cum-horror in The Devil Wears Prada really modelled on Wintour? (She attended the flick’s New York premiere wearing the label, by the way.)

Flanked on the Beijing stage by Vogue’s poised director of special events Sylvana Soto-Ward, its business-like fashion news director Mark Holgate and Vogue China’s effervescent editor-in-chief Angelica Cheung, composed Wintour has had the crowd eating from her expensively manicured hand. She has been gracious, charming and engaged.

“They were all so polite and well behaved,” Wintour says while settling in for our post-event tête-à-tête. “That’s quite unusual.”

The supposedly iron-fisted tastemaker disarmingly enquires where her interviewer comes from and how long he has lived in China. Couture’s uncontested uberfuhrer, it seems, is not at all averse to chummy chit-chat. It is her first visit to China and she appears impressed.

“I wouldn’t underestimate anything about this country right now,” says Wintour. Her impenetrable shades remain, as they will all morning (Wintour’s sunnies are fitted with corrective lenses, she has referred to them as her “armour”, and where else would she put them but on her face? She doesn’t care for handbags).

“I believe there is a fashion week in Beijing. Whether China will ever have a fashion week on the same scale as what we have in Paris or Milan or in New York, I couldn’t say, but growth here has already been so extraordinary. It’s fascinating. There is such an explosion going on. It’s fantastic. There is such appetite for fashion.”

IT IS SOON APPARENT that 61-year-old Wintour, with more than two decades at the helm of Vogue under her belt, is a polished operator and big-picture interviewee. She answers questions in broad but diplomatic strokes and parries when she deems it necessary.

Wintour has, after all, frequently been a lightning rod for tirades against her field, notably on issues such as fur (characteristic quote: “Fur is still a part of fashion, so Vogue will continue to report on it”), skinny models (she has come around: “We need to reverse the tyranny of sample clothes that just barely fit a 13-year-old on the edge of puberty”) and elitism (Wintour has been accused/credited with wiping out the early-1990s grunge look).

Asked for her perspective on up-and-coming Chinese designers, she says she does not have the experience to comment. The topic of Asian models, however, is perfectly timed for her and Vogue. “It’s incredible how that has changed in the last year or two years,” Wintour says. “You see so many more Asian models on runways these days.”

“Everybody seems to think they are a fashion editor, or a photographer, and everyone has an opinion and access to fashion in a way that they never had before. That makes our job particularly challenging”

Anna Wintour

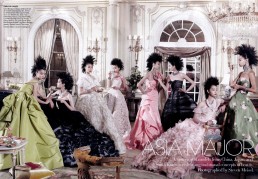

Wintour enthusiastically flips through the latest, December issue to a lavish spread by veteran fashion photographer Steven Meisel, the snapper behind Madonna’s notorious 1992 book Sex.

Under the headline “ASIA MAJOR”, the Vogue shoot features eight models: China’s Du Juan, Liu Wen, Bonnie Chen and Lily Zhi, Koreans Hyoni Kang, So Young Kang and Lee Hyun, and Japan’s Tao Okamoto. Accompanying text describes how Asians have increasingly cat-walked into the limelight in recent years.

“We saw Liu Wen, with her sculptural, diamond-shaped cheekbones, at Lanvin, Oscar de la Renta, Michael Kors, and more,” it reads. “Tokyo-raised Tao Okamoto, she of the Beatles bowl cut, walked for Givenchy, Carolina Herrera, and Ralph Lauren (she has also appeared in the label’s ad campaign). The full-lipped, hypnotic-eyed Feifei Sun from Shandong, China, appeared in 39 shows in her second season.

“And these women are not just selling high fashion. Poised, porcelain doll–faced Du Juan (she trained as a ballerina in Shanghai) and Shu-Pei Qin, her brows like accent marks, loom large on Gap billboards; Estée Lauder recently took on Wen as a new face, the first ethnic model since Liya Kebede, in 2003, to represent the classically American beauty powerhouse; and Qin, from Henan, China, has signed a contract with Maybelline.”

Wintour continues: “Grace Coddington, my creative director, and I were discussing it when we came back from the collections last season. We were particularly impressed by Oscar do la Renta’s collection and we wanted to do something special.

“Grace said, ‘You know what, I think we should shoot a whole story with Asian girls.’ Five years ago this would not have been possible. They are all extraordinary and beautiful.”

THE SHOOT, PRESENTING the East’s finest decked out in evening gowns and sporting gravity defying faux-mohawk hairdos, has been criticised, however. At the Huffington Post, contributors going by the name “Disgrasian” — self-described as “two Asian American chicks who grew up in the heartland” — took umbrage at Vogue’s assertion that Asian models are “redefining traditional concepts of beauty”.

Disgrasian wrote: “There are plenty of places in the world where, traditionally speaking, Asian women have long been considered beautiful. Like in, um, Asia, for example?”

Such grumblings have since been mulled over in new media worldwide, including on blogs from Britain’s Daily Telegraph newspaper, the Financial Times and New York magazine.

Later, Vogue China’s Beijing-born Cheung will bristle at such comments and spring to Wintour’s defence. “At Vogue China, we have been making huge efforts to promote Chinese models overseas and it is great to see such real support from my American colleagues,” Cheung says.

“They actually do something about it instead of just talking. I find the criticisms irrelevant because it is so easy to criticise others who make an effort. I would say to any detractors, ‘Show us what you have done to support Asian models.’”

DURING THE BEIJING forum, Wintour hinted at aloof indifference to such unsolicited opinions when asked how Vogue sustains its influence and clout (the US edition sells over 1.2 million copies a month; a 2007 issue of the magazine, the creation of which was chronicled in documentary The September Issue, reportedly reached a staggering 13 million readers; copies can be snapped up on eBay for around US$100).

“It’s a particularly interesting time right now,” Wintour said. “Everybody seems to think they are a fashion editor, or a photographer, and everyone has an opinion and access to fashion in a way that they never had before. That makes our job particularly challenging and even more useful, because there is an awful lot of noise out there; everyone thinks they are an expert.”

She went on to state that Tom Ford “so hates” the internet’s influence on fashion that he invited only 100 guests to his September show in New York. Reporters from daily newspapers were excluded.

“None of us were allowed to photograph the collection — although we managed to sneak around that with Grace’s wonderful drawings,” Wintour recalled. “But [Ford] gave Vogue magazine an exclusive for that particular collection because he is trying to bring back into the industry some sense of fashion being special again, and I think Tom has a very valid point. Sometimes women feel that clothes are overexposed by the amount of [coverage] they get online.”

WHILE HER VISIT to Beijing will prove to be part pleasure (with sightseeing on the Great Wall, in the Forbidden City and at the galleries of the 798 Art District) and part fact-finding mission, Wintour sees her role at Vogue as semi-ambassadorial for the US fashion industry. She says American brands have been relatively dawdling in entering the China market compared to their European counterparts.

“Dolce & Gabbana … I know they were just here [in China, in Shanghai],” she says. “They loved it. They just adored it. They came straight to New York afterwards and they were full of stories.

“The American design community cannot afford to ignore the strength of this market, and my understanding is that there are a lot of [retail] properties being looked at right now by key American designers. And I certainly plan to go back to the US and encourage them to come here.

“It’s going to be a huge market for them. There’s a limit to the amount of growth possible in the US, so we all have to look at the emerging countries for expansion.”

Wintour has previously expressed the opinion that politics and fashion do not make comfortable bedfellows. In a 2006 interview in Britain’s Guardian newspaper she opined, “Washington is frightened of fashion. I think the British government is the same … People in political office tend to get extremely nervous about fashion because they feel it’s frivolous. And they don’t want to look too elitist or too silly or whatever it may be.”

Recalling that statement in Beijing, Wintour grins. “Well, actually, I think, thanks to the first lady in the US, that has all changed,” she says. “[Michelle Obama] really has been a standard bearer for fashion. She obviously enjoys it, and she wears it so well. She has been so incredibly supportive of young American talent, of designers like Jason Woo, Derek Lam, Narciso [Rodríguez], Michael Kors, and by being so careful of the designers she wears when she goes abroad, so I think that’s really helped shift opinion.

“And I’m very impressed by Mrs Cameron, and I think that she has already announced that she’s going to take a leadership role in supporting British fashion. So, I think, with Mrs Cameron and Mrs Obama in place, we have a lot to be grateful for.”

And of the fashion she has witnessed on Beijing’s nippy winter streets? “I notice a lot of really interesting hair, I have to say. The colours and cuts are fantastic.”

Wintour suddenly becomes the most animated she has been all morning, and for a brief moment, perhaps, reveals an endearing glimpse of the shy teenager who, in the swinging London of the 1960s, rebelled against her school dress code by taking up the hemlines of her skirts.

“It seems to me that, among young people, there has been an explosion in self-expression here. It’s great,” she says.

“And I see a lot of hats. The Chinese seem big on hats.” ◉

Highlights from Anna Wintour’s Q&A session with students from Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts

On visiting the Beijing offices of Vogue China

“It reminded me of when I started out in London. I was working for Harper’s & Queen at the time. We had a tiny staff and basically you had to do everything: take pictures, write captions, cover the market, do the layouts, follow up … To me, that was the best training.

When I came to the US and American Vogue, I discovered we had a shoe editor, and a lady in her 90s who was the fabrics editor. There was an underwear editor … there were so many layers, and I think that’s not always helpful to understanding the industry.”

On The Devil Wears Prada and The September Issue

“I enjoyed the movies. I thought that they were highly entertaining and they were extremely kind to me because, of course, actually I beat all my assistants, I lock them up in cupboards and none of them get paid.”

On nurturing emerging talent

“When I first met John [Galliano] he did not have enough money to take a taxi. I would lend him money for fares; he would sleep in my hotel room. I used to fly him over from London to New York because I felt it so important for him to meet the right people. I helped him find investors. We really went to everybody and everywhere to support John because we realised he was a unique talent, and it’s Vogue’s responsibility to nurture and support talent as much as we possibly can.”

On the Chinese fashion industry

“From an American point of view, China is becoming an incredibly important market. Everywhere you go there is this great drum roll that started five years ago, asking, ‘What do you think about China?’ We decided it was time to make our own visit and to form our own opinions. I think American brands are a little bit behind in coming to China and I want to encourage them all to visit, to come and open stores here. We are behind the Europeans in that regard.”

On setting out on a career in fashion

“Fashion does not exist in a vacuum. Fashion reflects culture; it reflects our times. A great fashion photograph can tell you just as much about what is going on in our world as any headline or TV report, so go out, go to the galleries, go to the theatre, read books, travel … All of that will come back to reward you later.

“I was so lucky as a young girl growing up in London. I travelled as much as possible. That kind of exposure takes you through life in a different way. Particularly today, when everything is so incredibly global. It’s important to get out there to see for yourself. You really can’t learn only by looking at a computer screen.”

On assessing a designer’s work

“Well, I’m not always right, that’s for sure. The most important thing is to be honest. Designers have friends, the press and whoever rushing backstage to tell them they are wonderful. That may be very nice to hear but it’s not always constructive for someone trying to develop a business.

“Vogue always tries to be helpful and to tell the truth. It’s equally non-constructive to completely knock somebody. We gently try to explain our point of view and what we think they might try and change, or what a collection might be lacking. Then they usually go ahead and do whatever they want to do anyway.”

On her professional life with Vogue

“I feel I’m the luckiest person in the world. I have the best staff in the world. I’ve been doing the job for 100 years and I still can’t wait to get to the office every morning. The wonderful thing about fashion is that it changes all the time and, if you are working for a magazine like Vogue, you have the opportunity to work with the most incredible talent.” ◉

Wintour made her first visit to China in November 2010. Versions of this interview then ran in Hong Kong's South China Morning Post (download PDF) and Abu Dhabi's The National (PDF).

SHARE

Tom Dixon in Macau

Visiting Macau for an exhibition of his most sought-after creations, British design’s favourite maverick Tom Dixon celebrates royalty, sustainability, regionality and not really knowing what he’s doing.

AWARDED AN OBE for services to British design in 2000, and with his creations gracing the permanent collections of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, Tom Dixon has earned his seat among the world’s most on-trend designers of homeware.

Since 2002, he has helmed his eponymous company Tom Dixon (the smart money’s go-to for quirky lighting and conversation-starting furniture; for irreverent, zeitgeist-y home accessories) and been embraced by the chattering classes. And yet the labels most often pinned on the softly spoken 55-year-old are “maverick” and “rebel”.

“‘Maverick’ is getting harder and harder to justify,” says Dixon, taking a break from the media pack that has converged on the Louis Vuitton store in Macau’s plush One Central mall for the opening of an exhibition of his most iconic pieces. “At the same time, some people are saying I’m now ‘establishment’.

“The problem with the modern world is that you can’t shake anything off — people just add to it. I’d like be seen as more multi-layered, and maybe have to live with ‘establishment maverick’ or some other kind of hybrid.”

DIXON HAS COME south having just attended an exhibition of British creativity in Shanghai, where he gave visiting Prince William a hurried lesson in welding for media cameras. “Luckily, he did better than expected,” Dixon says of the second in line to the British throne. “It was close to a disaster, that stunt — the machine jammed three minutes before he arrived. He’s a class act, however. I was impressed.”

Being able to weld is important to Dixon. Welding, after all, is the humble skill he exploited to carve out a glamorous career, and which now has him hobnobbing with royalty.

“British history is littered with people who were non-experts … I would never have attempted three-quarters of what I’ve done if I’d been any good at it”

Tom Dixon

Born in Tunisia to a French-Latvian mother and an English father, Dixon was raised in London from the age of four. He dropped out of art school as a young man to play bass guitar with Latin-tinged dance band Funkapolitan, which enjoyed minor chart success in the early 1980s.

A love of motorbikes — and occasional need to repair them — saw him scouring junkyards for scrap parts and learning how to weld. Soon, in tune with the post-punk DIY ethos of the time, Dixon was salvaging iron grates, scaffolding and other metallic detritus to forge one-off pieces that he called “welded salvage furniture”.

“I’ve always found that I’m better off when I don’t know too much about something, so I don’t come loaded with preconceptions,” Dixon says of his lack of formal design training. “I like to come to projects with slightly more child-like eyes.

“British history is littered with people who were non-experts and came at things from a slightly different angle. I would never have attempted three-quarters of what I’ve done if I’d been any good at it.”

WITH TIME, DIXON’S fresh, impudent approach caught the eye of the heavyweights of European design. One of the most successful of his early creations was his distinctive S-Chair, which was snapped up for manufacture by Italian luxury furniture giant Cappellini. The chair was modelled on a doodle of a chicken that Dixon had made on a napkin.

In the early 1990s, his polyethylene “sitting, stacking, lighting thing” — simply called Jack — made his design aesthetic recognisable the world over. Dixon’s Mirror Ball lights, encased in highly reflective glass spheres, have since become part of the contemporary design landscape from Beijing to Buenos Aires.

Dixon, however, who described his 2013 book Dixonary — which explores the highlights of his career so far — as “illuminations, revelations and post-rationalisations from a chaotic mind”, is surprisingly dismissive of his triumphs.

“It’s very satisfying to know that some of my work has gone into museums and appears in design books, but I can’t ultimately say that I’m really very satisfied with anything,” he says. “I’m quite self-critical, and that’s what makes you do the next piece.”

“You do get a certain guilty feeling producing more stuff in a world that doesn’t necessarily needs loads more stuff”

Tom Dixon

While he argues that London — home to Tom Dixon the brand — and that city’s “openness to the world” offers advantages for a designer working on the international stage, he wonders if the concept of design as a universal language transcending national borders is flawed.

“The iPhone has managed to do that quite well, but I think people retain a sense of place,” he argues. “An analogy that works, I think, is food. For a long time everybody was into ‘fusion’. What people want now is ‘authentic’, ‘real’ and ‘original’ food.

“New Scandinavian design — this quite sensible, pastel-y approach — is very successful right now, so I think national identities are being maintained. You can tell Japanese design, for instance, a long way off.”

And while Dixon recognises that consumerism and the constant reinvention of products lie at the heart of the design industry (for 10 years, kicking off in 1998, he was head of design and then creative director at £500-million-turnover British retail legend Habitat), he says he increasingly aims for longevity in his work by avoiding trends and insisting on high craftsmanship.

“You do get a certain guilty feeling producing more stuff in a world that doesn’t necessarily needs loads more stuff,” he says. “I have an interest in sustainability. I think every designer should. I’m old enough now to have quite a lot of stuff that has gone into the secondary market, and the things that survive are those that look better with age, and that’s a quality I strive for.”

ULTIMATELY, DESPITE HIS many successes, Dixon’s autodidactic beginnings still appear to inform his aesthetic and sensibilities. When the subject of exclusivity is broached, the maverick and rebel — if only momentarily — appears to break through the media-savvy gloss.

“I have some trouble with that word,” he says when asked if Tom Dixon products are “luxury” goods, “but I can’t deny that they are expensive. I’m atypical of most designers, having worked at all kinds of levels.

“I worked for Habitat when it was part of Ikea. When I first started, I was selling things for 15 quid just to get rid of them and start the next one. I’ve worked in proper luxury — with the Italians — as well, so I’m going to go for ‘reassuringly expensive’.

“The context here, of course, in the LV Gallery, is a super, hyper-luxury context, but I see my stuff in rough bars, and I’ve seen very cheap copies of my lamps in Starbucks in Shanghai. So, in a way, I’ve achieved affordability through being copied.” ◉

This story was commissioned by Hong Kong Tatler magazine in 2015. Download PDF.

SHARE

When You're Strange

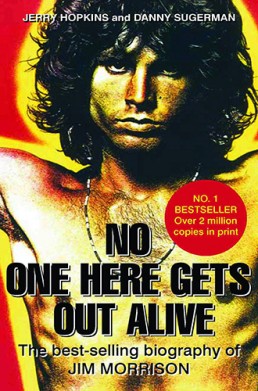

The cult author of No One Here Gets Out Alive, Jerry Hopkins reflects on the Doors frontman’s mysterious death, on Frank Zappa’s 'musical bicycle', on Hunter S Thompson’s alarming wardrobe, and on getting busted thanks to 'the most dangerous man in America'.

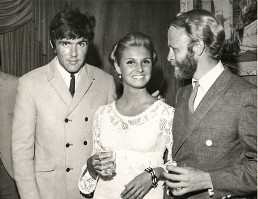

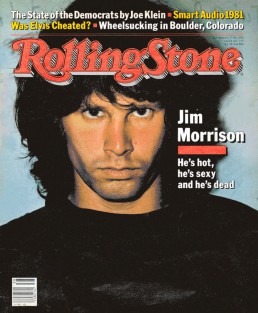

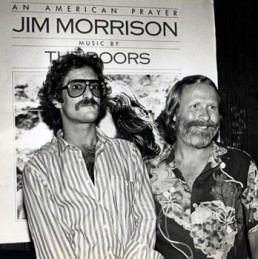

THE BRAZEN HEDONISM and exotic strangeness of Bangkok agree with writer Jerry Hopkins. Cult author of No One Here Gets Out Alive, the definitive portrait of 1960s psychedelic rock band the Doors’ frontman Jim Morrison, Hopkins has been described as “the dean of pop biographers”. He laughingly refers to himself as a free-spirited “bottom feeder” and a fortunate “Jerry Gump”.

“I’ve been in the right place at the right time often in my life, just like Forrest Gump,” says the 77-year-old American, who also penned the first ever bio of Elvis Presley, as well as accounts of Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie and Yoko Ono. As Los Angeles correspondent for Rolling Stone magazine in the late 1960s, Hopkins experienced the highs and lows of flower power in full bloom.

“Being in LA in the 1960s was the right place if you were going to write about music and the youth revolution, or whatever you want to call it, and that’s what I did, and that’s where I was, and I had a helluva good time.”

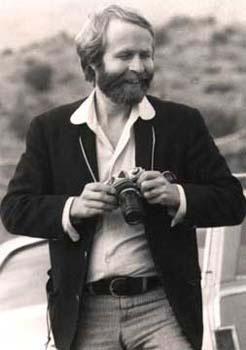

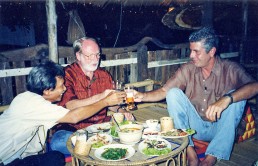

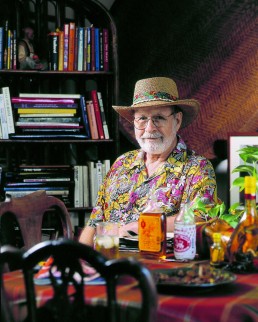

FOUR TIMES MARRIED and with two grown-up children in the US, Hopkins has lived in Thailand since 1993, and his Bangkok apartment nestles on a downtown side street. Frangipani blossoms float over garden walls, and scarlet-backed flowerpeckers, white-vented mynas and other tropical birds perch in its knotted banyan trees.

With his thinning grey hair and trimmed beard, thick spectacles, beige slacks and gaudy Hawaiian shirt, the writer has the avuncular air of a retired civil servant.

A short stroll from Hopkins’ restful hideaway, however, lies the Thai capital’s main thoroughfare of sex-tourism, Soi Nana, off Sukhumvit Road, where street stalls ply hardcore porn DVDs and Viagra (about 10 bucks for four of grandpa’s little helpers), as well as chromed knuckledusters, ninja throwing stars and equally dangerous-looking sex toys.

“Being a bottom feeder has a long literary tradition,” says Hopkins. “There’s a whiff of danger about Bangkok. I hate to romanticise dirt, but we’re talking whores and drugs and the fun things in life. Life’s more fun as a bottom feeder.”

Over almost half a century, Hopkins has delivered three-dozen books covering everything from rock-chick groupies and the history of the condom to spoof astrology and aphrodisiacs. He has, by his own admission, enjoyed an unconventional career by chasing down the outré and the bizarre.

No One Here — the first rock biography to reach number one on the New York Times bestseller list — has never been out of print since 1980, selling in the millions worldwide.

“Morrison was the most interesting of all the rock stars I met because he was the best conversationalist,” Hopkins says, reaching into his refrigerator, the door of which sports Doors and Presley fridge magnets. “Something I always had trouble with at Rolling Stone was that I was interviewing people whose avenue of communication was singing or playing an instrument.

“Why should anyone expect them to have a political opinion worth listening to? Most of them didn’t, but Morrison was interesting on a totally different level.”

HOPKINS POURS TWO glasses of iced tea, changes the battery in his hearing aid and sits to reminisce on sex and drugs and rock’n’roll — on Morrison’s perplexing death in Paris at the age of 27, on iconoclastic writer Hunter S Thompson’s weird dress sense, and on his own penchant for transsexual street hookers.

We begin in the year the Doors signed their first record deal. The soundtrack to that heady 12 months featured the Byrds’ Fifth Dimension, Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde and the Beatles’ Revolver.

“1966 was a great year,” says Hopkins, recalling how he had already “tucked a flower behind my ear” and embraced the countercultural zeitgeist. “I guess ’67 was the ‘Summer of Love’, but ’66 was when all the great records came out.

“Things were getting terrible in Vietnam and civil rights was bubbling away, but we thought we were gonna change the world. We really believed that, and I don’t think any generation since has shared that level of … I would prefer to use the word positivism as opposed to naiveté.”

It was 1966 when Hopkins and a friend opened what was only the third “psychedelic store” or “head shop” in the United States. Los Angeles was “a headquarters” for the prevailing drug culture, he says, so that would be the name of their store.

“Headquarters was the first head shop in Los Angeles. I didn’t even know what a head shop was. I’d been working in TV and I’d grown uncomfortable. My buddy was in the same mental state, so I said let’s quit and open a store. It must have something to do with drugs.”

“We were the community centre for the hippy generation. Kids would hang out in the afternoon so they didn’t have to go home to mom and dad. They could be with these hip guys who openly sold rolling papers”

Jerry Hopkins

The shop was in Westwood, close to the UCLA campus that provided its core customer base. The choice of location owed as much to lechery as utility.

“As my partner put it, ‘I fell in love more times per block than in any other neighbourhood.’ We were the community centre for the hippy generation. Kids would hang out in the afternoon so they didn’t have to go home to mom and dad. They could be with these hip guys who openly sold rolling papers.

“We sold lapel buttons, which were a big thing at the time: Save Water, Shower With A Friend; Even Paranoids Have Real Enemies, and the like. We had Peter Fonda posters, Bob Dylan posters, and a selection of maybe 15 underground newspapers from across the country.

“When the brass band of [minor league hockey team] the Los Angeles Blades changed their uniforms, we got the old ones. We sold them as Sergeant Pepper uniforms. Harrison Ford, an out-of-work actor and carpenter at the time, sold us Fillmore dance posters.”

It wasn’t long, however, before similar stores — taboo-breaking purveyors of roach clips, hash pipes and assorted drug paraphernalia — were sprouting like magic mushrooms from coast to coast, and Hopkins takes “blame” for their proliferation.

“Headquarters had been open for about six months,” he explains with a boyish chuckle, “when I was quoted in Newsweek as saying, ‘We’re gonna gross US$50,000 this year if things continue as they’re going.’ I could just hear dopesters all over the country saying [adopts a clichéd stoner voice], ‘Hey man, let’s open a head shop.’

“My partner’s father couldn’t understand how we could possibly make $50,000 a year when there was nothing in the shop costing more than a dollar. He suspected we were dealing drugs, and I think a bit of that might have been going on. Typewriter cases changed hands in the store. I’m not sure they always contained typewriters.”

BORN IN 1935 in New Jersey, Hopkins’ long and strange trip from Quaker roots to Californian bohemia began significantly earlier than the ’60s. The author claims that two of his ancestors had come to the US on the Mayflower.

“I have that kind of colonial history,” he says. “My early settler antecedents founded my little hometown in 1720. All kinds of stuff there is named Hopkins. My parents were not particularly religious, though — it was a heritage thing to send me to the Quaker school. My father drove the school bus, so I got free tuition.”

Strangely, it was conflict rather than peaceniks that guided “the last kid to be picked for the baseball team” in his unusual career.

“During World War II, I would read the dispatches of [Pulitzer Prize-winning correspondent] Ernie Pyle. He covered Europe and then the Pacific. He died in the Pacific, in fact. I decided that was what I wanted to do when I grew up: travel the world, meet interesting people, write about them and get paid for it. I was aged nine then, and I’ve never wavered.”

After university in Virginia, a graduate degree from Columbia University in New York, two years at a newspaper in New Orleans and a stint in the army in Georgia, Hopkins found himself back in the Big Apple.

“I worked as a writer-producer on a Mike Wallace show, but it never really got traction or an audience, so it got canned,” he says. “Mike went onto much greater things at CBS and I was asked if I wanted to go west to work for Steve Allen, who’d invented The Tonight Show. It was 1962. I was in a marriage that wasn’t working. Hell, she had thrown me out and I was sleeping on a friend’s couch, so I headed for LA.

“Steve needed somebody who could come up with an off-the-wall person, or an act, that Steve could bounce off for comedy effect, five nights a week. So I became his ‘vice president in charge of left-fielders’. I was Steve’s ‘kook-booker’. Some of the people were genuinely strange.”

FINDING CRANKS AND eccentrics to appear on the new The Steve Allen Show proved easier than Hopkins had imagined.

“You find safe little corners. Circus people, for instance — a fire-eater, a wire-walker — took care of 12 scattered evenings. The whole idea was to get people to teach Steve something outlandish. This, of course, was southern California, where all the nuts and flakes wound up. That helped. Even today I think, ‘Wow, I got paid for that?’”

Hopkins searched out zany nonconformists from the proto-hippies, “health weirdos” and other subcultures cautiously edging into mainstream in the early 1960s.

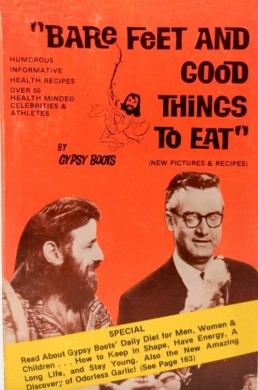

“There was a bunch of people who almost lived in the trees,” says Hopkins. “The most famous was Eden Ahbez, who wrote the song Nature Boy that became a big hit for Nat King Cole. Eden and a bunch of others represented the early fruits-and-nuts bunch. One was a fella who called himself Gypsy Boots.”

Hopkins first met Boots in 1962, while the kook booker was having his hair cut by Jay Sebring, later to become stylist to heavy-hitter celebrities like Warren Beatty and Steve McQueen, as well as to Morrison himself (Sebring would be murdered alongside actress Sharon Tate by members of the Manson Family in 1969).

“Gypsy came in selling health-food sandwiches,” Hopkins says. “Long beard, long hair, fast-talking, a little bit crazy. He became a good friend.”

Boots would become a regular guest on the show, sharing his eco-friendly outlook and once cajoling Allen into milking a goat on camera. “In fact the first book I ever wrote was his life story,” says Hopkins, of Boots’ ghost-written Bare Feet & Good Things to Eat (1965). “I never made any money on it. Never wanted to.”

Another oddball was a pre-fame Frank Zappa, who Hopkins first met in 1963.

“He called and told me he wanted to teach Steve ‘musical bicycle’. I knew it was a put-on, and Steve had always insisted no put-ons, but Frank sounded interesting, so he came along.

“He played the spokes like a harp. He beat on the seat and blew at the handlebars. He would not admit it was a joke. Then, years later [in 1966], suddenly here comes Frank Zappa. He’s got long hair and a funny Zapata moustache and a new album called Freak Out!”

Frank Zappa plays musical bicycle on 'The Steve Allen Show'. Video: DRMUX/YouTube

HAVING BECOME DISILLUSIONED with television, and later with the head shop suffering financially (“The big department stores started taking our business — if you wanted a poster of Peter Fonda, you could get it at the May Company”), Hopkins found himself at a loose end. But another golden opportunity would soon present itself.

“Back then, Rolling Stone was a twice-monthly newspaper, tabloid size. I’d seen a box in one of the early issues — we sold Rolling Stone in the store. They were soliciting for freelance submissions, so I sent in a review of a Doors concert. They printed it and sent me a cheque for US$15. I thought, ‘This is terrific.’”

Soon, Hopkins became San Francisco-based Rolling Stone’s Los Angeles correspondent (he remained on the publication’s masthead for 20 years as a contributing editor), interviewing Morrison several times.

“I wasn’t a close friend of Jim, but more than an acquaintance. I really liked the Doors. I thought they were …” Hopkins sighs, polishing his glasses. “They were worthy of attention as musicians, and I thought Jim’s drunken-asshole antics got in the way of them getting the respect they deserved.

“That first article [about the Doors] was a little critical. I called Jim pretentious. He deliberately threw himself into the audience and I thought that was a little precious, but I really liked their lyrics and I really liked Morrison. We drank in the same bars and he would invite me to poetry readings and screenings and stuff. I went to Mexico for a week with them, and toured with them on the West Coast.”

“It’s true that Jim was a drunken asshole, but that wasn’t all he was. He read more books and was more articulate than anyone else I’ve ever met in the entertainment world … He was a poet”

Hopkins on Jim Morrison

Hopkins gleaned many personal insights into Morrison while covering the Los Angeles music scene, and film director Oliver Stone used Hopkins’ interview notes, as well as No One Here, as backbone to his 1991 biopic The Doors. The movie’s release resulted in the biography bounding back to the top of The New York Times bestseller list, this time to the number-two spot, but the writer is conflicted about Stone’s cinematic portrayal.

“The look of the movie was bang on,” Hopkins says. “It was like being whiplashed into my past. Oliver had everything very accurate visually, which is interesting [considering that] 40 per cent of the screenplay turned out to be total fiction.

“It’s true that Jim was a drunken asshole, but that wasn’t all he was. He read more books and was more articulate than anyone else I’ve ever met in the entertainment world. He had a sense of humour about himself. He didn’t take his stardom seriously. He was a poet. He was a lot of things that Oliver ignored.”

Hopkins has only praise, however, for the movie’s star. “Val Kilmer was brilliant. He had Morrison down. Before shooting, Oliver wanted to fly me to LA — I was living in Hawaii then — to ‘pick my brain’.

“I said there’s nothing more in there. It was 1990, after all. I’d sold [Stone] my interview transcripts, some 200 in total, and he’d bought the book rights, but he flew me to LA to have dinner with him and Val anyway.

“I got there early and there was no reservation for a Mr Stone, so I walk into the bar and there’s Jim Morrison talking on the wall phone. It was Kilmer, of course, already wearing the leathers and the long hair. He looked just like Morrison. My first thought was, ‘I’d forgotten Jim was so tall.’ Kilmer really did a good job, but Oliver sees the 1960s differently from the way it was.”

Hopkins also disagrees with Stone’s painting of Morrison’s girlfriend Pamela Courson as long-suffering casualty of the rocker’s philandering and boozing.

“Jim suffered too,” Hopkins says, laughing aloud. “Pam was a piece of work — absolutely beautiful, but very demanding, very jealous. She was a heroin addict. She played around herself. She was wild. Let’s just say she was Jim’s match.”

IN THE OFFICIAL French police report concerning Morrison’s death, Courson found the singer dead in their Paris apartment’s bathtub on July 3, 1971, apparently of a heart attack. He was quickly buried in the French capital’s Père Lachaise Cemetery. Conspiracy theories regarding the exact circumstances have multiplied ever since.

“I get blamed for this,” says Hopkins. “The Morrison book was written in 1972, 1973, and it wasn’t published for seven years or so. My original plan had been for two different final chapters. One ending would have Jim overdosing on a combination of heroin and alcohol. [In the second version] he faked his death and, like his idol, the French poet Rimbaud, he wandered off to North Africa to gain the freedom that anonymity would give him. He was fed up with being a star.

“I suggested that if the publisher were to print 10,000 copies of the book, 5,000 should have one ending, and 5,000 the other. Distribute them and don’t say anything, which I still think is an interesting concept. [The publisher] said that was too much trouble, and to put the two chapters together, end the book ambiguously, which I did.

“So now, many people say that book created the controversy over whether Morrison is dead or alive, and of how he died, and blah, blah, blah.”

“The risks he took, in terms of the drugs and alcohol, and the quantity … In a way it’s almost a miracle that he made it to 27”

Hopkins

Hopkins insists that the true cause of Morrison’s death had been “very well established long before my book came out”, and the writer is not culpable for crackpot theories.

“America lets go of its heroes very reluctantly,” Hopkins says. “It’s quick to build them up and slap them down, but it doesn’t want them to die, and Morrison did die under mysterious circumstances. He was in the ground before anyone had announced his death, and there was no autopsy. Well, no autopsy was required.

“Jim and I shared an agent, and a publisher and an editor (there were a lot of coincidences between him and me), and the agent told me that once she was having dinner with Jim and beat poet Michael McClure. She told me that Jim had said that he felt like an old man, close to death.

“The risks he took, in terms of the drugs and alcohol, and the quantity … In a way it’s almost a miracle that he made it to 27.”

AT THE TIME of Morrison’s death, Hopkins had just wrapped up the book Elvis: A Biography, which he had undertaken on the personal suggestion of Morrison, who had been fascinated by Presley. With that book on the shelves, the writer rejoined Rolling Stone in 1972. He was soon sent to cover the British music scene from London.

“It was the year after Morrison died, and I went over to Paris to research his death,” Hopkins says. “Everybody I spoke to told me he’d suffered a heroin overdose in the Rock’n’Roll Circus nightclub, and that he had been carried home. Well, what do you when somebody has an overdose?”

Hopkins says a bath of cold water was commonly considered helpful to drug users suffering from a surfeit of heroin.

“And that’s where he died, in a bathtub. But the truth would have caused problems for others present, so they created this lie that he’d had a heart attack. A doctor came and there were no signs of violence or foul play. It was the 4th of July weekend, which was no big deal for Paris but the American embassy was closed. [Morrison] was in the ground in a hurry.”

Hopkins admits, however, that he is troubled to this day by Morrison’s reported use of heroin. “That had not been his drug,” insists Hopkins. “Jim did do a lot of cocaine, but his drug of choice, since long before he died, had been alcohol.

“In my Rolling Stone interview with him in the early summer after the Miami arrest [for indecent exposure onstage] of March ’69, he said that he had switched to alcohol because it was so much easier to obtain [than illegal drugs]. You just walked into a store, put your money on the counter and they gave you a bottle. He didn’t want the hassle any more.”

DRUGS AND ALCOHOL, unsurprisingly, played significant supporting roles in the California hippy scene of the late 1960s and early ’70s, and there was a dark side to the adulation, money and “other perks” that young musicians gained so quickly. Hopkins recalls a psychedelic folk-rock combo that he attempted to manage in the mid ’60s.

“There was this band, man, playing at a club called Bido Lito’s. It was just an alley joint,” he remembers. “I thought Love were just fucking brilliant, and so a friend and I became their managers. We took them into a studio and recorded four or five songs, but we didn’t know what we were doing, and the quality was terrible.”

Love, under new management, went on to release a series of albums, including the critically acclaimed Forever Changes.

“A couple of other guys in the band got heavily into heroin,” Hopkins says. “[Singer and Love figurehead] Arthur Lee was a handful himself, but an extremely talented songwriter and guitar player. Love, like a lot of bands, was thrown together in a hurry and fell apart because they got, in the words of Bill Graham, the famous concert promoter, too much too soon.

“These people become household names before they have callouses on the fretting fingers, and by the time they get callouses they’re whatever-happened-tos.

“Buffalo Springfield was another perfect example. There were too many huge talents in that band to survive. The Byrds went through enormous changes for the same reason. [Founding Byrds member] David Crosby was impossible to deal with. Drugs were a real problem in maintaining personal relationships.”

Music insiders have said that Lee’s addictions gave rise to a self-destructive personality — rarely playing gigs, being uncaring to fans and dismissive of the media — and that he had the star quality to have been as big as Mick Jagger, John Lennon or, indeed, Morrison.

“Well I didn’t see that,” Hopkins says. “Arthur was deliberately eccentric. He’d stand on stage wearing one combat boot, and he had these little psychedelic crystal glasses, green in one eye and red in the other, and his hair was Bob Dylan-esque and uncontrolled. Charismatic? I dunno. It was the music that pulled me.”

HOPKINS ALSO QUESTIONS the merits of celebrity journalists spawned during the period, notably Hunter S Thompson, creator of the experimental “Gonzo” style of writing in which reporters position themselves as central characters in their stories.

“I’m from the old school,” Hopkins says. “Gonzo journalism was about never letting facts get in the way of a good story. I believe the exact opposite. You can still have a style, still have a personality, but you don’t make things up.

“Hunter and the other big-name writers that came out of Rolling Stone started to arrive as I left. When they hired me to go to London, they had a big editorial conference in Big Sur and Hunter came. The first thing that hit me was his wardrobe.

“He wore Bermuda shorts, a polo shirt, running shoes and white gym socks. He was bald, he used a cigarette holder and he sounded exactly like [typecast nice-guy actor and staunch Republican supporter] Fred McMurray — kinda wholesome.”

“Hunter Thompson was a phenomenon unto himself, and an excellent one, but he killed his talent with alcohol”

Hopkins

Thompson soon built on the cult success of his 1971 Gonzo classic Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas with Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, which in part covered the re-election strategy of President Richard Nixon.

“Later, I thought, ‘No wonder Nixon talked to Hunter Thompson. He dresses just like one of them,’” Hopkins says. “Hunter Thompson was a phenomenon unto himself, and an excellent one, but he killed his talent with alcohol.”

The No One Here author is candid about his own drug intake over the years. “I never took LSD,” he says. “Long ago I decided wasn’t going to touch chemicals. I took peyote, mescaline, marijuana, hashish, hash oil, cocaine, which comes from a plant. I could have done heroin, I guess, with that distinction.”

Despite Hopkins’ rejection of the ’60s hallucinogen of choice, that drug was responsible for the writer suffering an alarming brush with the law. And not for possessing or using LSD, but for supposedly supplying, and to none other than Timothy “turn on, tune in, drop out” Leary.

“I was in London and Tim Leary was on the lam in Switzerland, having escaped from jail in California. I was given an assignment to write a story about him, so my [second] wife, who was pregnant, our young daughter and I went. We spent five days with Tim Leary, and he was just so charming and perfectly wonderful. We had a great time.”

In 1973, Leary was re-arrested, extradited to the US, and sent back to jail. Hopkins, at the time was living in Mendocino, three hours north of San Francisco and then a hippy enclave, and the authorities mistakenly decided that a letter he sent to Leary — who Nixon had described as “the most dangerous man in America” — had been dosed with acid, and that Hopkins must be running an LSD factory.

The family home was raided. No such factory was found. Though the offending letter came back clean, Hopkins and his wife were charged with possession of marijuana and drug paraphernalia (misdemeanours) and cultivation of marijuana (a felony), and were found guilty. With a defence based on illegal search and seizure, the case was eventually rejected by the superior court.

“Leary, when he finally got out, thought it was hilarious,” says Hopkins.

THOUGH NO ONE Here Gets Out Alive, which been translated into 16 languages, has made Hopkins royalties for 32 years and counting, he insists he has not lived off the proceeds alone.

“I think I’ve been paid for two million [copies],” Hopkins says. “The publisher of the English edition alone told me that she had sold a quarter of a million. I think the accurate sales figure is four [million] worldwide, but I don’t know.”

Officially, No One Here was co-authored by the late Danny Sugerman, but Hopkins says his partner’s input in the writing was “almost none”.

Sugerman had idolised Morrison and answered fan mail for the Doors as a teenager. “There were two manuscripts. One was the size of the Manhattan telephone directory and my editor said cut it down, so I cut it down to the Bronx, and then he rejected it.”

The book was passed over by 30 further publishers, and when Hopkins decided to quit trying (after seven years), Sugerman stepped up to the plate for 10 per cent commission. He succeeded in selling the biography to Warner Books, even though that same company had already twice rejected the work.

“Danny then said he would like to take the two manuscripts and put them back together again. He would get Michael McClure to write an afterword, he would write a foreword, he would do the discography, he would do all the crap that I did not want to do, so I said, ‘Okay, you’re in for 30 per cent and you’re my co-author, and you can have 50 per cent of the movie rights,’ which I didn’t think were worth anything.

“If it hadn’t been for Danny, there would not have been a book. So I’ve never once had any regrets.”

“My feeling now is that I didn’t take to being rich and my idea was to get poor again as soon as possible, so that I could be happy again”

Hopkins

How much money has No One Here made Hopkins, so far? “I have no idea,” he says.

Millions of dollars? “Hell, no. I’ve lived comfortably, and I tried to shovel as much of it up my nose as I could, living well beyond my means at times, in retrospect. I ended up in bankruptcy court [in 1986] and divorce court [from his third wife, having moved to Hawaii in 1976]. I haven’t had a credit card ever since, so some good came of it.

“My feeling now is that I didn’t take to being rich and my idea was to get poor again as soon as possible, so that I could be happy again.”

Hopkins rediscovered his happiness in the arms of Vanessa, a transsexual prostitute of Polynesian descent who worked the streets of Honolulu’s Chinatown. “I was in love with her, I shared my bed with her, on the nights when she came home,” he says, chuckling at the memory. Hopkins has been “totally fascinated with that lifestyle” ever since.

WITH DAYLIGHT FADING, we decamp from the writer’s bolthole to stroll Sukhumvit to Nana Plaza, Bangkok’s neon-lit warren of go-go bars and clip joints that is arguably the largest single compound of paid-for sexual gratification on the planet. We order beers and survey the spectacle that Hopkins described in an earlier email as “what Morrison called ‘the soft parade’ — in this instance the whores going to work, the men streaming in after them, the first exiting on ‘dates’”.

The pleasingly anarchic Thai capital, Hopkins insists, is inspirational to his work. When not trawling licentious Bangkok, however, he lives with his fourth wife — who is Thai, 25 years his junior and who he met in Nana — and her extended family on an idyllic rice farm close to the border with Cambodia, and six hours drive from the city.

“We have 12 types of fruit, four fish ponds,” says Hopkins. “We raise frogs, chickens, ducks … It’s quiet. We have no telephones, no internet.”

Thailand, with its contrasting extremes, appears to be the right place for this time in Jerry Gump’s deliberately unorthodox life.

“I’m researching two books at the moment,” enthuses Hopkins, who recently penned the introduction to a forthcoming volume entitled Expecting Rain — a compilation of poetry by tough-guy actor Michael Madsen (ear-severing psycho Mr Blonde in Reservoir Dogs). “One is about ladyboy sex workers and the other is called Whore Lovers: The Aficionados & Connoisseurs.”

Hopkins carries out much of his “research” at Cascade, a go-go bar that is headquarters for more than 100 transsexual prostitutes, including, he laughs, one chisel-jawed individual whose nickname is “Lights Out”, and not for her after-dark activities but for her devastating Thai boxing skills when silencing difficult customers.

“All of that strikes me as a hell of a lot more interesting,” the kook booker says, “than what my daughter calls a ‘real job’.” ◉

Versions of this story ran in LA Weekly (download PDF) and Post Magazine (PDF) in 2013.

Jerry passed away in 2018. Read his obit in the New York Times.

SHARE

Kraftwerk

As Kraftwerk prepare to take their man-machine music back on the road, their influential co-founder — speaking from the group’s secretive Kling Klang Studio in Germany — explains how technology took time to catch up with their ideas.

CALLING THE KLING Klang Studio, to interview Ralf Hütter, enigmatic co-founder of pioneering electronic music-makers Kraftwerk, is intimidating.

It’s daunting enough that Hütter is one of the most influential figures in pop and rarely gives interviews, but there are also whispers that the telephone I’ve been instructed to call at Kling Klang, on the outskirts of Düsseldorf — and from which Kraftwerk have been making music for more than 40 years — has no ringer and so will remain silent.

Precise instructions have emanated from the studio to call at 11.20am Central European Time, on the dot. Once connected, I will need to input a pre-arranged eight-digit access code. The interview slot will last exactly 15 minutes, to end abruptly at 11.35am.

It’s a great relief, therefore, to reach Hütter (at 11.21am) without any technical glitches. The cheerful-sounding 66-year-old is, he says, still on a high after Kraftwerk’s eight-night residency at the Turbine Hall of London’s Tate Modern art gallery in February.

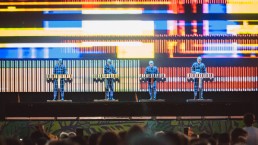

And in May, Kraftwerk will bring their multi-media extravaganza of clinical, repetitive beats and addictive pop melodies — all synchronised to visual projections, choreographed robots and cutting-edge 3D animations — to Hong Kong.

DEMAND FOR KRAFTWERK’S The Catalogue 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 performances crashed the Tate Modern’s website within hours of 10,000 tickets going on sale. A retrospective of eight Kraftwerk albums, with one album performed on each day, the gigs received uniformly gushing reviews: “Perfect performance art” (Daily Telegraph); “Kraftwerk still feel unique” (Guardian); “Mesmerising … Phenomenal” (BBC).

“It was a fantastic environment,” Hütter says of the London concerts. “There were a lot of artistic connections because Kraftwerk means electronic energy, electric energy, and the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall is an old kraftwerk.” His band’s name, Hütter points out, means power plant. “It’s an old, turbine-driven power station.”

Kraftwerk’s 3D performances, first unveiled at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2012, are the latest twist in the band’s four-decade-long career of pushing the limits of audio-visual technology.

Among the earliest users of electronic instruments, the four-piece combo’s signature sound has influenced bands and artists as diverse as the Human League, David Bowie, Bjork, Kanye West and Radiohead. In the run-up to the Tate Modern shows, Britain’s Observer newspaper described Kraftwerk as “still the world’s most influential band”, adding that “no other band since the Beatles has given so much to pop culture”.

KRAFTWERK’S MAN-MEETS-machine concept did not come about overnight. Hütter and original working partner Florian Schneider, who met as art students in Düsseldorf in the late 1960s, were just two of many homegrown musicians searching for a distinctively German sound and aesthetic that would differentiate them from American rock music and the popular British beat groups of the time.

Going by the name Organization, Hütter and Schneider experimented by mixing traditional music-making tools (notably Schneider’s flute, but also guitar, violin and other instruments, all processed with electronic effects) with primitive synthesisers and electric keyboards.

“We created a new electronic or contemporary, industrial, social musical language from zero. We didn’t have a language, so we created our own language”

Kraftwerk co-founder Ralf Hütter

Kraftwerk were formed in 1970 with the establishment of Kling Klang in Düsseldorf (the studio was relocated in 2009 to Meerbusch-Osterath, about 10 kilometres to the west). “We created a new electronic or contemporary, industrial, social musical language from zero,” says Hütter. “We didn’t have a language, so we created our own language.”

From the very beginning, Hütter says, the “Kraftwerk multi-media concept” was about much more than simply making orchestrated beeps, clanks and whirrs, and he frequently uses the word gesamtkunstwerk — which German composer Wilhelm Richard Wagner also employed, in the mid-19th century — to describe the bringing together of sound and visual media to create a “total artwork”.

“We played in galleries and arts centres more than in music [venues],” says Hütter, who has always been Kraftwerk’s prime source of lyrics. “We made videos, graphics, photographs, created album artwork … I am very much into words and tone poetry. Florian was into synthetic voices. Over the years, we worked with many different musicians, drummers, sound engineers and technicians, and today we are in 3D. It’s been a constant progression.”

KRAFTWERK’S BREAKTHROUGH came with 1974 album Autobahn. “It was our first electronic concept album — the beginning of what we call electro,” says Hütter, adding that Autobahn, logically, comes first in The Catalogue 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8. “Before that we had three albums of transition from electro-acoustic music, with tapes and all kinds of experiments, but the first masterwork is Autobahn.”

From Autobahn through the album Trans-Europe Express (1977) to the single Tour De France (1983) and album Tour De France Soundtracks (2003), transportation has been a repeating theme.

“It’s not so much about travel, which means going from here to there,” says Hütter, who is an obsessive cyclist. “We are more interested in movement, continual movement, without any goals. ‘Dynamics’ is a better description. Social dynamics and changes in society. I think that’s the main theme of Kraftwerk music.”

Despite Kraftwerk’s cold, robotic image, fans also appreciate the sly humour in the band’s work. The track Autobahn’s lyrics (“Wir fahr’n, fahr’n, fahr’n auf der autobahn,” or “We drive, drive, drive on the autobahn”) have been called “a very Teutonic homage” to the Beach Boys’ Fun Fun Fun. The 1975 album Radio-Activity features a track called Ohm Sweet Ohm.

Kraftwerk on BBC TV's 'Tomorrow's World' in 1975. Video: The Kraftwerk Database/YouTube

HÜTTER CLAIMS THAT Kraftwerk’s roots in Germany’s Rhine area, with tribal-Germanic, French, Roman and other European cultural influences competing and cross-fertilising through the centuries, has been the reason. “Humour is part of our cultural cosmos,” he says.

To many ears, the name Kling Klang — which can be translated directly from German as “sounding sound” — sounds daft, resonating like an onomatopoeic “ding dong”. Kraftwerk’s private studio, however, is something that Hütter speaks of extremely seriously, almost with reverence.

“Kling Klang is a music machine,” says the self-described musikarbeiter, or “music worker”.

“It’s not a building — buildings don’t make music. It’s changing all the time, incorporating and connecting all our instruments, our synthesisers, our computers, our visuals, our graphics and animations.

“In the second part of the 1970s, we couldn’t do concerts, and then again after ’81, and all the way through the ’80s, because we couldn’t bring Kling Klang Studio with us. Everything was so complex. In the ’90s, with the digital age, we transformed Kraftwerk onto laptops. Now we can travel to cities like Hong Kong with the Kling Klang Studio going with us.”

“We would play Kling Klang Studio live, and there was always failure. Cables would break, knobs and switches would fall off, but we just kept going”

Ralf Hütter

Being ahead of their time, says Hütter, who is the last surviving member of Kraftwerk’s Autobahn line-up (Schneider left the band in 2009), proved a logistical nightmare whenever they attempted to take their music on the road. But Kraftwerk’s 1970s vision of the future is now pop music’s present

“We would play Kling Klang Studio live, and there was always failure,” he says. “Cables would break, knobs and switches would fall off, but we just kept going. Technology developed and now, with digital music machines and computer programs, it is at the level where the Kraftwerk concept works. The machines have finally caught up with us.”

HÜTTER IS LOOKING forward to Kraftwerk’s May shows in Hong Kong, in other Asian cities and at the Sydney Opera House in Australia. Until then he will labour at Kling Klang, reprogramming music, graphics and animations.

With the interview’s 11.35am deadline having passed (we speak for 21 minutes in total), Kraftwerk’s longest-serving man-machine — who has proven pleasingly human in conversation — wraps ups by considering his role as the elder statesman of electronic music, which he finds motivating.

“It’s a source of energy,” Hütter says. “The feedback from all generations of electronic musicians is so encouraging — it keeps me going. It’s like what I wrote in the lyrics for [Kraftwerk’s 1983 single] The Robots: ‘We’re charging our battery/And now we’re full of energy.’

“The feedback is doing exactly that.” ◉

An edited version ran in Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post in 2013. Download PDF.

SHARE