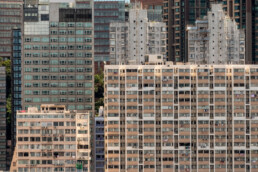

High-Density Hong Kong

LAMMA IS ONE OF Hong Kong’s outlying islands. There is a regular ferry service between Central district on Hong Kong island and Yung Shue Wan village on Lamma that takes about 25 minutes. For half of the journey, the ferry travels in parallel with the northern shore of Hong Kong island.

These photographs were taken from the ferry in July 2022. The aim was to capture the high-rise urban sprawl that extends from Central to Kennedy Town on Hong Kong island. ◉

SHARE

Cambodia's Floating Doctors

With the emergence of Covid-19, the world applauds its frontline medical staff, whose life-saving struggles usually go unseen. On Cambodia's massive Tonlé Sap Lake, a team of 'floating doctors' quietly cares for some of the most vulnerable people in Asia.

THE TONLÉ SAP LAKE in northern Cambodia is the largest body of freshwater in Southeast Asia. During rainy season from May to October, the lake swells to about six times its dry-season size, extending over 16,000 square kilometres — an area 20 times the size of New York City.

The Tonlé Sap is also one of the planet’s most productive inland fisheries. More than a million people are dependent on the lake for their livelihood, and about 100,000 live in its immediate vicinity.

While many dwell in stilted villages on the lake’s flood plain, the poorest huddle in floating communities on the lake itself, sometimes hours from dry land. Their homes are often fragile, rain-leaking shacks cobbled together from woven reeds, scraps of plywood, tin sheet and tarpaulin, all lashed to wooden or bamboo rafts kept afloat on air-filled oil drums.

They are among the most isolated communities in Cambodia, the majority relying on subsistence fishing for their survival.

According to the World Health Organization, Cambodia has just 1.7 doctors for every 10,000 people (both the US and the UK have about 26; Norway has 46). For floating communities on the lake, the number of accessible doctors had long been zero.

American Jon Morgan first became troubled by the lack of healthcare on Tonlé Sap in the 1990s, having recently completed his masters in public health at the University of Hawaii.

Morgan, who went on to co-found the Angkor Hospital for Children in the nearby Cambodian city of Siem Reap, noted that lake dwellers’ poverty, poor nutrition and hygiene, and the high fees for medical treatment only available far from home all combined to whip up a perfect storm of preventable diseases and treatable injuries that could ruin or end lives.

“I thought, my God, this is a nightmare,” says Morgan, 67. “Somebody has to do something.”

His solution was The Lake Clinic – Cambodia (going, rather neatly, by the acronym TLC), which became a reality in 2007, growing in scope and ambition ever since. Through the years, TLC has provided more than 240,000 individual medical services to those living on the Tonlé Sap.

Today, TLC operates five “floating clinics” — four on the lake and one on the adjoining Stung Sen River — catering to more than 10,000 people in nine of the most under-served floating communities.

With five doctors, two nurses, four midwives, a dental nurse and support staff, and funded purely by private donations, TLC’s two homegrown medical teams each make a three-day trip into the field every week. They live and work in the offshore facilities to provide free medical care and health education to the most forgotten people in one of the Asia’s poorest countries. ◉

Shorter versions of this photo essay ran in Hong Kong's Post Magazine (download PDF) and in The Providence Journal (in colour) in the US in 2020. Learn more about The Lake Clinic's work here.

SHARE

TLC FOUNDER JON MORGAN says there are at least 50 floating communities on the lake, jointly home to tens of thousands of people. Most eke out a living through fishing. The average family income is about 10,000 Riel (US$2.5) a day. Photos: Gary Jones

Midwives Ky Kolyan, Chan Soda and Chhuom Sary and a medical team cast off from TLC’s home port at Kampong Khleang. Their wooden boat heads for the floating clinic at Peam Bang, 50km to the south and home to about 200 families. The team’s journey to work will take more than four hours. They stay on the lake for three days each week, sleeping under mosquito nets on foldout camp beds in the floating clinics.

The boat, one of TLC’s fleet of six, navigates a channel through dense beds of water hyacinth. In high-water season, the lake has an average depth of about 10m. During dry season, that falls to less than a metre, and smaller, shallow-draft boats must be deployed.

TLC’s Peam Bang clinic sits on a pontoon anchored to the lake floor. Water depth at this location rises to about eight metres in wet season, the ‘bushes’ here actually being the tops of submerged trees.

TLC medical director Dr Hun Thourida unloads the boat. She has worked with TLC since 2012, after graduating from the respected St Petersburg II Mechnikov State Medical Academy in Russia. ‘Doctor Rida’ chose to return to her home country to help the needy. She is fluent in Khmer, English and Russian.

Chhuon Sary, supported by Doctor Rida and clinical coordinator Uk Savann, gets the Peam Bang clinic scrubbed and ready for action. TLC currently operates five floating clinics serving nine of the most isolated lake communities. The most accessible is 30km from port; the furthest is more than 100km away.

Three girls and their grandmother are caught in a shower while heading for the clinic.

On a busy day, a TLC clinic might welcome 100 patients. Most are women — mothers and grandmothers — with children in tow, and a smattering of older men. Unless seriously ill or injured, men of working age will be too busy fishing and tending nets to see a doctor. ‘These people live by the day,’ says Dr Hun Thourida. ‘What they catch is all they have.’

Common ailments on the lake include malnutrition and measles in the young, diarrhoea caused by drinking dirty water (a major cause of childhood death), infected wounds (often from the propellers of outboard motors), tuberculosis, fungal conditions, malaria, dengue fever, complications from diabetes, respiratory infections, severe tooth decay and burns, as well as hypertension and arthritis in older patients.

A woman sorts through her catch while waiting to see a doctor. Catches have fallen drastically on the Tonlé Sap over the past decade due to overfishing, pollution and hydropower-dam building upstream — most notably in Laos and China, on the Mekong that feeds the lake via its tributary the Tonlé Sap River.

Nurse Suon Piseth checks the blood pressure of all patients on their arrival at the clinic.

TLC measures and weighs lake children under the age of five every six months, charting their growth. Cambodia as a whole has a 32 per cent malnutrition rate, according to TLC data, rising to 59 per cent on the lake. Malnutrition is especially common among youngsters, with fish caught or farmed by their families usually being sold.

Diets therefore revolve around rice, chilli and salt, lacking in protein, fat and micronutrients. ‘Two-thirds of the kids on the lake are stunted due to chronic malnutrition,’ says Jon Morgan. ‘To their families, fish has more value as a commodity to sell than as nutrition.’

Doctor Rida pays a house call by boat to a woman unable to reach the clinic. The doctor has been treating the 28-year-old for Pott’s disease — tuberculosis of the spine — that could have resulted in paralysis. The woman lives with her small daughter, her mother, who has Parkinson’s disease, her father, who lost a leg to gangrene, her sister, who also has TB, and her sister’s husband — the family’s sole breadwinner. The woman’s husband disappeared when she became unwell.

A mother takes her sick daughter’s temperature with a digital thermometer; Chhuom Sary vaccinates a toddler against diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough.

Children play outside a family’s floating home. According to the most recent Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey, one in every 29 Cambodian children dies before his or her fifth birthday, with the mortality rate ‘markedly higher in rural areas’, or one in every 19 under-fives. On the lake, young death comes even more readily. Dr Hun Thourida says lake families often have as many as 10 children, with many not surviving to adulthood. ‘Some drown between the age when they start to crawl and when they learn to swim,’ she says.

Dr Hun Thourida says many lake dwellers have no opportunity to live on land, with many effectively stateless, their births never having been registered. Such people cannot own property, get a job and pay tax, obtain a driver’s licence or open a bank account. ‘Fishing is all they know. Because of poverty they are stuck,’ she says. ‘They were born on water and they will die on water.’

Everything is designed to float at Peam Bang — including homes, mechanics’ workshops, livestock pens and chicken coops. Some lake communities have floating schools and churches, while convenience stores sell instant noodles, potato chips, candy and sugary drinks to those who can afford them. Tooth decay is increasingly a problem due to poor oral hygiene.

Ky Kolyan explains the dangers of consuming lake water. TLC encourages the use of bio-sand filters. ‘We have to tell them, the water might look clear, but you poop in the water and you pee in the water, so it’s not good to drink,’ says clinical coordinator Uk Savann.

TLC has established a ‘Mother’s Club’ in each community, with counselling on antenatal care, hygiene, birth spacing and contraception. The goal is to decrease maternal and infant mortality rates.

A poster at the Peam Bang clinic instructs on how to build and maintain floating vegetable gardens. Crops include water spinach, cabbage, lemongrass, spring onions, tomatoes and eggplant. Families can sell any surplus.

Patients paddle for home. Though many fishing families have access to boats with outboard motors, for those living farthest from land, travel for a medical emergency could cost up to 200,000 Cambodian Riel (US$50) in diesel fuel, an amount that is prohibitive to many families. The Lake Clinic, therefore, travels to those most in need, also providing transportation to faraway hospitals in urgent cases.

After three days on water, it is time for the TLC team to lock up the clinic and return to land. ◉

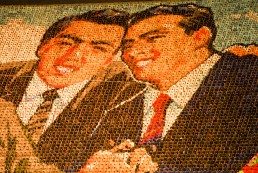

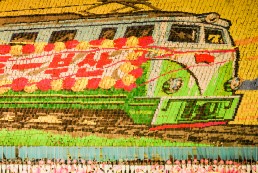

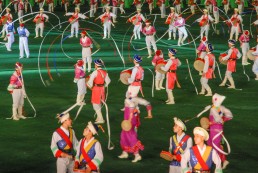

North Korea's Mass Games

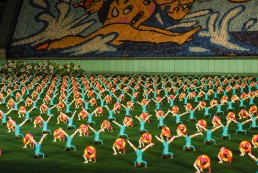

THESE PICTURES WERE taken during two visits to North Korea’s Mass Games in 2007. Held in the Rungrado May Day Stadium in the capital Pyongyang, the Mass Games is a choreographed propaganda spectacle incorporating the performances of up to 100,000 gymnasts, athletes, martial artists and dancers. Since 2002, the Korean folk tale Arirang — a story of separated lovers, used as a metaphor for the divided peninsula — has been a regular visual theme. ◉

Photos from this set were published in Time, Columbia Journalism Review, Globe & Mail, The Australian, Boston Phoenix, Southeast Asia Globe and The Correspondent, among others.

SHARE

The Funfair

THIS PICTURE SERIES was taken during a week-long documentary photography workshop held in the ancient city of Luang Prabang in northern Laos. The workshop was headed up by veteran Australian shooters Jack Picone and Stephen Dupont, and each participant was asked to “produce a documentary photo essay with a striking visual narrative”.

I tried to do that by spending time with a travelling funfair that was pitching its tents on the edge of town. Despite their initial growls at having a camera constantly shoved in their faces, the young men building the fair were won over with a bribe: three crates of Beer Lao. ◉

Some of the pics in this series ran in online photography magazine Life Force.

SHARE

Rome's Doll Hospital

For more than 60 years, a devoted Italian family has been nursing broken dolls back to health from their creepy shop in Rome. As their neighbourhood gentrifies, the proprietor wonders how much longer the tradition will survive.

ROME BOASTS MANY attractions with disturbing histories, from the blood-soaked Colosseum to the skeleton-filled Capuchin Crypt. And on a cobbled alleyway in one of the city’s most fashionable neighbourhoods, a small shop window offers another seemingly gruesome glimpse into the Italian capital’s past.

Behind the dust-dulled glass, unblinking eyes stare from decapitated heads. Severed arms, legs, hands and feet hang in bunches from rusty nails. This little shop of horrors, known locally as l’Ospedale delle Bambole, or “the Hospital of the Dolls”, was established by the Squatriti family more than six decades ago.

Body parts have been accumulating there ever since.

CRACKED PAINT PEELS from the weathered window frame of the “hospital”. Inside, Federico Squatriti, 52, and his 82-year-old mother, Gelsomina, continue a family tradition of nursing broken antique dolls back to health, and paint-spattered walls, cobwebbed shelves and busy workbenches are cluttered with fractured figurines, wounded toy soldiers and mangled puppets.

“It has always been owned by our family, so we haven’t changed anything,” says Federico of his cramped and fascinating atelier, which has become a macabre and offbeat tourist attraction in recent years. The ramshackle workshop — a halfway house for refugees from the most sinister of fairy tales — sits just a stroll from the sparkly Gucci, Versace and Dolce & Gabbana boutiques on Rome’s swanky Via dei Condotti.

“It looks like an old-fashioned shop because it is an old-fashioned shop,” Squatriti says. “It’s looked the same since the beginning.”

He takes a fading black-and-white photograph, taken in the 1970s, from a shelf. “This picture is more than 30 years old,” he says. “This is my father, when he was still alive, and my mother. Look how many things there were, all scattered everywhere. This is how we work every day, with so many beautiful objects all around us.”

HAILING FROM NAPLES, Federico’s grandfather, Vincenzo Squatriti, was an actor with the respected La Scarpetta theatre company in the 1950s. Under the stage name Enzo Petito, he later worked alongside silver-screen legends Gina Lollobrigida and Marcello Mastroianni, and even had a minor role as a gun-store owner in Sergio Leone’s classic 1966 spaghetti western The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

Before that, in the wretched years following World War II, Vincenzo’s wife, Concetta, decided acting to be too unstable a profession for her family’s future. “My grandmother urged her children to learn a craft because acting didn’t make much money after the war,” Squatriti says.

Though struggling with rising materials costs and crippling rent in one of Rome’s once working-class but now gentrified and touristy neighbourhoods, Federico Squatriti is reluctant to turn away new patients

In 1953, Concetta opened Restauri Artistici Squatriti (Artistic Restorations Squatriti) in Rome with her two sons: Federico’s father Mario and his uncle Renato. “Since then all my family has worked here,” Squatriti says of their tiny workplace, which covers about 150 square feet. The still air is acrid with enamel, glue and solvents. “My grandmother, my father, my uncle, my aunt, my cousins, my mother and myself.”

Squatriti cannot remember when he joined the family business. “We lived in an apartment upstairs, and when I was young and returned from school, I would drop by to say ‘hi’ to my dad, my grandma and my uncle,” he remembers.

“I don’t recall exactly when one of them first said, ‘Federico, please help with this.’ I started out by returning restored items to customers, then I would be sent off to buy materials, and little by little I ended up working here too.”

THE SQUATRITI BUSINESS initially survived by restoring ceramic, tortoiseshell, metal, ivory, wooden and mosaic heirlooms damaged during the war for Rome’s aristocracy — the only people who could afford such a luxury at the time. Dolls came later.

Historically, the earliest dolls date back to ancient Egypt, Greece and, indeed, Rome (Roman rag dolls have been found dating back to about 300BC). Their heyday arrived in the 19th century, and the bodies of European dolls at that time were roughly hewn from leather, wood or papier-mâché, and hidden under fanciful costumes of lace, silk and taffeta. Their heads, however, were increasingly made from delicate porcelain and starting to look creepily real, with detailed eyelashes, beauty spots, even wrinkles.

“The best solution is to work well and work long enough. It’s something you do for your customers, not just for money”

Federico Squatriti

They were no longer children’s playthings but collectors’ items for the moneyed elite. Squatriti lifts one such doll’s head from a shelf, cups it in a hand and brushes away generations of dust.

“It’s more than 100 years old,” he says of the antique, which is inscribed with the year 1902. Many items in the shop are unclaimed toys of children long grown old or passed away, he adds. Some have been there for decades and will likely never be reclaimed. “We started to restore dolls’ heads because they required the same methods as other porcelain items,” Squatriti says.

TODAY, UP TO 1,000 period pieces — plates, vases, statuettes and more, as well as many dolls — are looked after every year at the Restauri Artistici Squatriti workshop, and Federico Squatriti, like any dedicated family doctor, feels a profound responsibility for his clients’ wellbeing. Though struggling with rising materials costs and crippling rent in one of Rome’s once working-class but now gentrified and touristy neighbourhoods, he is reluctant to turn away new patients.

“If I wanted to work only seven or eight hours a day, I would need to charge more, but then fewer people could afford to restore their dolls and their antiques,” Squatriti says. Dozens of cold, creepily human-looking eyes appear to watch as he speaks.

“The best solution is to work well and work long enough. It’s something you do for your customers, not just for money. It’s satisfying for me, at the end of the day, to say to myself, ‘I’ve worked for 11 hours, the result came out beautifully, and I managed to do it for a reasonable price.’

“The people are happy and I am happy. It’s all beautiful!” ◉

This ran in Post Magazine (PDF) in 2015. The pictures were published that year in Mail Online and Panorama magazine in Italy, and later in online photography magazine Life Force. The Guardian chose one picture for its globally sourced 'Photo Highlights of the Day' in April 2015.

SHARE

Carnival of Carnage

Every year on the Thai island, hundreds of Chinese spirit mediums — known as 'horses of the gods' — perform extreme acts of self-mutilation, piercing their faces with swords, golf clubs, umbrellas, even handguns.

NESTLING OFF THAILAND’S west coast, the popular holiday island of Phuket has a permanent population of some 500,000 people, and its beaches, agreeable turquoise waters and welcoming hotels and villas pull in five million tourists a year.

Phuket is also home to more than 2,000 Chinese spirit mediums who, their believers believe, have a supernatural ability to connect with the great beyond.

Every year, to gain spiritual merit, they undergo ceremonial self-mutilation during Phuket’s annual Vegetarian Festival, which the world’s tabloid newspapers have variously called the “carnival of carnage”, a “bazaar of the bizarre” and the “gala of gore”.

THE VEGETARIAN FESTIVAL runs for nine days starting on the first day of the ninth month of the Chinese lunar calendar. This year it ran from September 27 through October 5, and on every one of those days Phuket’s spirit mediums, known locally as mah song, or “horses of the gods”, publicly slashed at themselves with swords and cutlasses and axes.

Some hacked at their tongues with serrated saws, blood dribbling down bare chests to leave great gobs of coagulating crimson gunk in the streets. And many more mah song underwent ritual piercing of their cheeks with skewers and knives.

And with golf clubs, badminton racquets and umbrellas; with handguns and with power drills; with motorcycle exhaust pipes and assorted automotive spare parts; with bunches of flowers, bunches of green bananas, with table legs and butcher’s hooks and musical instruments and with rows of glued-together dominos.

One gent thought it a good look to scar himself for life by puncturing his face with a radio-controlled model helicopter.

THE ORIGINS OF the festival are unclear. What is known is that Phuket was once a thriving centre for tin mining and many Chinese migrants worked there in the early 19th century (people of Chinese ancestry comprise a large proportion of Phuket’s population to this day). They lived in jungle conditions. Malaria and other tropical maladies were rife.

Sometime around 1825, a travelling opera troupe arrived from China to perform for the miners, but the musicians soon became sick with fever. Deeply superstitious, the troupe prayed to their gods and stuck to a vegetarian diet to honour them. When the sickness afflicting the troupe disappeared, the miners wondered how they had survived.

Ritual vegetarianism had been their saviour, the minstrels replied, and the festival has been held ever since, with Phuket’s Chinese community observing a 10-day vegetarian diet for purposes of spiritual cleansing.

HUMAN BUTCHERY WAS added much later, with mah song entering trances to be perforated on shrine grounds before joining lengthy processions through Phuket’s streets. Recent decades have seen mah song driven to ever greater extremes of mutilation, seemingly simply to stand out from the crowd.

Though the merit-making piercings should only make use of weapons mentioned in Chinese legends (swords and bladed staffs, for instance), it’s significantly easier to get your face in newspapers with the mischievous misuse of a ukulele, or a couple of ukuleles, or a bicycle pump, or an entire bicycle.

This year, one festival organiser called for Chinese shrines taking part — Phuket has about 40 shrines — to issue identity cards to mah song. Prasert Fakthongphol, president of Phuket Shrine Association, told the Phuket Gazette newspaper that this would “preserve the integrity of the spirit-medium community” and deter “fakes”. Such identity cards would feature each mah song’s name and photograph, and details of the god that possesses him or her.

Terrified at the thought of his coming suffering, the 27-year-old hacked the tongue out of a pig’s head … and wedged the cold organ into his mouth

Charlatans have, indeed, occasionally popped up in Phuket. In 2006, woodcarver Paitoon Khopwej was to join a procession. Terrified at the thought of his coming suffering, the 27-year-old hacked the tongue out of a pig’s head, skewered it with a sword and a saw blade, and wedged the cold organ into his mouth.

When his deception was discovered, Paitoon was beaten bloody by an angry mob, and elders at one shrine filed a complaint with police. The chastened woodcutter eventually served 15 days in Baan Bang Jo jail for “deceiving the public”.

THOUGH A BURLY, impressively tattooed fisherman stumbling through a torrential downpour with a ceremonial dagger or a significant chunk of a palm tree rammed through his filleted face makes for an arresting photograph, it is difficult to speak with the mah song during the festival. Not only are their vandalised mouths often spilling over with gore and saliva, but they are also clearly off with the fairies.

On day six of the festival this year, with one of its largest street processions just over, one young man shelters at a stall outside Phuket Town’s Jui Tui temple. The stall-holder punts polystyrene trays of mango and sticky rice for Bt30 (less than a dollar).

The young man is not interested in food, however. His lacerated and swollen face is held together with medical plasters, and he sucks gingerly on a Krong Thip cigarette (though officially, mah song are not permitted to smoke during the festival). He is not in the best of spirits.

Asked how it feels to wander across Phuket for three hours in a monsoon with a sword stuck through his face, he says he “cannot remember”. And how does the gloomy penitent feel now? “Tired,” he answers, dazed.

And with that, and without a goodbye, he stumbles away to be washed clean in the rain. ◉

Versions ran as a travel story in Post Magazine and as a photo essay in That’s Shanghai, way back in 2011. Download PDFs.

SHARE