Cult American comedian Andy Kaufman spent his final days seeking a miracle cure for cancer on the operating table of a wealthy Filipino psychic surgeon, hoping that healing hands could succeed where Western medicine had failed. Fifteen years later, with a new Kaufman biopic starring Jim Carrey in cinemas, a question remains: are such faith healers for real, or are they just crooks?

“He was the Neil Armstrong of comedy. He went places no one else had gone”

— Jim Carrey on Andy Kaufman

SLEEVES ROLLED UP and eyes closed in prayer, psychic surgeon Jun Labo summons up the healing powers of the Holy Spirit, plunging both hands into his patient’s stomach. Blood spurts up his arms and across her chest.

Much kneading of grey flesh and the faith healer re-emerges triumphant, a dripping black mass of organic matter in his fist. The caption to the photograph reads, “Labo removes a large tumour from cancer patient with dexterity and care.”

The book Jun Labo — A Philippine Healing Phenomenon is not for the squeamish. Illustrating the work of the world’s most famous psychic surgeon, another caption reads, “Labo lifts eyeball out of its socket and inserts his left index finger under the eyeball to clean it.” And then there’s “a haemorrhoid being pulled out after psychic surgery”.

Readers will cringe as Labo makes “mucus, pus and phlegm ooze out of this Canadian patient’s throat”, squirm as “a worm appears from this patient’s stomach, possibly the victim of witchcraft”.

Believers claim Filipino psychic surgeons have a heaven-sent ability to perform miracles — to reach into the ailing human body without a scalpel or anaesthesia to cure everything from flatulence to cancer.

Sceptics, however, say it is a wicked scam, and that Labo and his paranormal pals have become rich by charging terminally ill American, European and Japanese patients up to US$200 a minute to perform a street-conjurer’s tricks, the tools of their trade being concealed packets of blood and offal from chickens, cows and pigs.

A BETTER READ IS Andy Kaufman Revealed! Best Friend Tells All, Bob Zmuda’s account of the bizarre life and untimely death of the cult American comedian who played bumbling mechanic Latka in the much-loved, early-1980s sitcom Taxi.

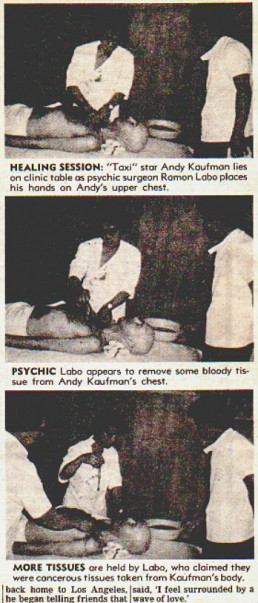

The book’s closing chapters describe how, in March 1984, a painfully thin Kaufman, suffering from advanced and inoperable lung cancer, had set out on a quest for a miracle. Given just three months to live by doctors in Los Angeles, he rejected Western medicine and made a 12,000-kilometre pilgrimage to Baguio, a ramshackle town high in the Philippines’ Cordillera mountains.

Believing Kaufman’s end was drawing near, Zmuda followed. In Baguio, he witnessed his friend — now sporting a Mohawk to disguise hair loss from chemotherapy — go under the psychic knife of a certain Jun Roxas twice a day for a month. Stripped to his underwear, Kaufman would wait with other patients for Roxas’s attention, shivering on an international production line of the sick and dying.

Once it was Kaufman’s turn, Roxas would appear to rip open the comic’s chest with his bare hands and remove great gobs of cancerous tissue. He then seemed to reseal the wounds with nothing but the power of prayer. Kaufman passed away on May 16, 1984, at the age of 35, less than a month after returning to the US.

Time and grief may have clouded Zmuda’s memory. Perhaps, as executive producer of one of the most anticipated Hollywood blockbusters of the year — the Kaufman biopic Man on the Moon, directed by Milos Forman (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest; Amadeus) and starring Jim Carrey — Zmuda has changed the surgeon’s name to avoid legal irritations.

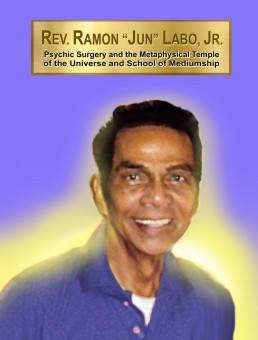

But, the fact is Roxas does not exist. Kaufman’s psychic surgeon was Ramon Labo Junior, better known as Jun Labo.

‘AH, YES, MR KAUFMAN,’ says Labo, squirming on an ornate white-wood and red-velvet throne. Surrounded by gaudy figurines of a bloody Christ and a weeping Madonna, the flamboyant faith healer is uncomfortable recalling a high-profile patient who died in the face of divine intervention.

“Mr Kaufman was very sick when he came to me. He was very skinny, very weak. The cancer had gone too far. I couldn’t help. He is with Jesus now.”

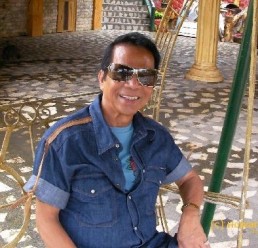

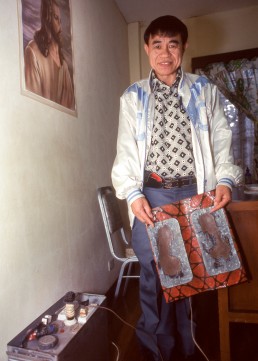

Labo is 65. He looks 45. He is short, lean, self-assured and tanned to peanut butter. His big hair is blow-dried. His small eyes are hidden by 1970s sunglasses. But the most striking thing about him is his jewellery.

On one wrist, a huge diamond and ruby-encrusted gold watch. On the other, a custom-made, gold identity bracelet big enough to scare Puff Daddy. It, too, flashes with diamonds. Labo looks at once daft and sinister. He chain-smokes Marlboro Menthols.

After thousands of dollars of treatment, Zmuda says his friend left Baguio only when his surgeon pronounced him cured. Labo claims he knew he could not help within two days of Kaufman’s arrival. “Mr Kaufman cried and insisted that I keep trying,” says Labo. “After all, he was already here. He had cancer. He was dying. He had nothing to lose.”

Like Hollywood, it seems Baguio might be a place where fact and fiction are blurred for financial gain.

LABO’S OFFICE IS in the basement of the Nagoya Inn, the healer’s surreal, paint-flaking hotel for the sick and wretched that reeks of mould and despair and cockroach killer that doesn’t kill cockroaches.

On a mist-shrouded Baguio hillside, beyond Lourdes Grotto and Holy Ghost Hill, the Nagoya’s garden is slippery with rain and the shit of ducks, chickens, deer and goats that wander listlessly among a frozen freak show of life-sized plaster sculptures — busty mermaids, leaping lions and battling samurai. The Nagoya’s gift shop sells “I Love Jun Labo” T-shirts.

According to the Philippines Medical Association, there are fewer than 50 practising psychic surgeons in the Philippines. The most powerful are in Baguio, where acts of God are common. The town is hit by at least 20 typhoons a year, and accompanying mudslides sweep the corrugated-iron shacks of the poor to the foot of the valley.

In 1990, an earthquake measuring 7.7 on the Richter scale killed 1,600 people in 45 seconds. Life and death revolve around the Immaculate Heart of Mary Cathedral, perched high on a hill in the centre of town like colossal, pink-iced wedding cake.

With his ostentatious lifestyle and cocky manner, Labo is the most controversial of all the healers. Followers call him a misunderstood saint, the Elvis of faith healing, the pope of Baguio. Many more say he is a cynical, dollar-eyed crook with contempt for human suffering.

“I don’t do this for money … I have been chosen by Jesus Christ to heal the people of the world and spread the message of God”

Psychic surgeon Jun Labo

In a nation where the average Catholic family of six barely survives on US$130 a month, he is certainly wealthy. Across the road from the Nagoya, two Mercedes and a 1935 Rolls-Royce sit inside a high-walled compound patrolled by armed guards and snarling dobermans. A Ponderosa-style sign across the tall iron gates declares it to be “Jun Labo’s Residence”. Labo is chauffeured the 100 metres to his office every day in a Space Wagon with tinted windows.

Labo says 80 per cent of the “tens of thousands” of patients he has treated have been cured of afflictions that include cancer, Parkinson’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. He declines to talk about money. “For tax reasons,” he says. “I don’t do this for money. I am being used by the Holy Spirit. It is not my choice. I have been chosen by Jesus Christ to heal the people of the world and spread the message of God.”

Pushed, and he cannot resist bragging. Since the early 1980s, Labo says he has treated more than 100 foreign patients a week at an average rate of US$50 a session. A quick calculation sees his annual income top US$250,000, not including additional revenue from patients paying to stay at the Nagoya.

In 1984, when Kaufman visited Labo, a critical newspaper reporter said the healer was a peso millionaire. According to his biographer, Labo smiled and said, “The report is wrong. He should have said I’m a billionaire.”

LABO’S FIRST PATIENT of the session arrives. The young, well-dressed Filipina has acute period pain and goitre, a swelling of the neck due to deficiency of iodine in the diet and swelling of the thyroid gland. Labo leads us down a corridor lined with photographs of him healing the multitude. Others show Labo high-kicking in his karate gear and chatting with the late Hollywood actor Burt Lancaster.

We pause for Labo to pray in his spooky chapel, the nerve centre of his Metaphysical Temple of the Universe. The 32 white pews face a metre-high pyramid-like frame that Labo sits under to meditate. The dominant colours are papal white and gold, but the chapel is a confused mish-mash of Catholic, Zen and new-age iconography. To ensure the largest possible market, Labo advertises that he can cure Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, pagans, atheists.

Beyond the chapel, Labo’s surgery is a simple white room dominated by a mournful portrait of Christ and a porcelain statuette of Mary. The patient strips to her underwear and lies on the operating table.

“Watch carefully,” Labo says with a mischievous glint in his eye. What happens next is pure theatre.

LABO SLIPS ON a white surgical gown and rolls up its sleeves. His huge watch and bracelet stay. He closes his eyes to summon up his spirit guide — a native American Indian named Rama, apparently — and he enters a trance.

Labo moves fast and sure. He rests his hands on the woman’s abdomen and a red liquid oozes from his fingertips. Within seconds, he is splashing in a deep crimson pool and a dark stringy discharge appears. He flicks it onto her heaving chest.

Labo’s hands are visible throughout, except when his fingers are sunk deep into the woman’s fleshy midriff. If his performance is sleight of hand, it is extremely well executed.

After rinsing in a bowl of water, Labo keeps his hands in full view and moves to his patient’s neck, where there is no excess flesh in which to hide. Again, blood and matter appear from nowhere. The only logical explanation — divine intervention aside — is that Labo’s assistant, who is constantly replacing soiled towels and shifting fresh ones into position around the patient’s body, is leaving covert props for his master. The entire performance lasts perhaps a minute.

“It was a frame up. They are jealous and they want to destroy me”

Labo, on his recent arrest in Russia for fraudulent practice of medicine

Labo can see I am impressed and he is pleased. But his smile disappears when I bring up Moscow.

According to the Russian and Filipino press reports, Labo was arrested in September last year (1998) for the fraudulent practice of medicine in the Russian capital having treated a nine-year-old boy for a brain tumour.

Labo charged US$1,500 for 10 sessions. When the child’s condition deteriorated, his father went to the police. They raided Labo’s surgery, according to the reports, allegedly to find a stash of cattle blood and entrails in the refrigerator.

“It was a frame up,” Labo says, claiming the boy’s father was in the employ of his political enemies. Labo, who has twice been Baguio’s mayor, also claims the newspapers are being paid to discredit him. “They are jealous and they want to destroy me,” he says.

After six months in Russia, Labo was released in March 1999 thanks to the efforts of Joseph Estrada, the former B-movie actor turned Philippines president, who petitioned Russian Prime Minister Yergeny Primakov for his friend’s release. Estrada also ensured that Labo received VIP treatment while incarcerated in Moscow. “It was like living in a comfortable hotel,” he boasts.

Over the years, Labo has worked hard to maintain good, if morally suspect, political connections. In the early 1980s, he says he rose at 5am each day to board a private plane to Manila, where he would treat the late Philippines dictator Ferdinand Marcos for a kidney ailment. Labo remembers those days fondly. “The president loved me very much,” he says, “because I allowed him to urinate again.”

An appreciative Marcos — who, legend has it, believed the Philippines to be situated under a hole in the universe through which cosmic forces entered — would then rub down a tired Labo with Vick’s Vapour Rub, the healer confides.

Labo also claims he has also treated Libyan strongman Muammar Gadaffi, for heart trouble, as well as the wife of former South Korean president Chun Doo-Hwan, the man responsible for the massacre of 2,000 students protesting his military dictatorship in 1980.

“I will help anybody,” says Labo. “Rich? Poor? It’s all the same to me. I am a simple instrument of the supernatural being we call Jesus Christ.”

THOUGH LABO MIGHT think he is God’s gift, Baguio does not. Rarely leaving his fortified compound, myths have sprung up around the healer like a creepy Filipino Boo Radley. “Labo is number-one quack doctor,” splutters my jeepney driver into town, offering a sarcastic thumbs up and laughing so hard he almost chokes. “He makes good hocus pocus.”

“Nobody in Baguio believes in Jun Labo,” rants Tony, a beefy miner in a “Couples For Christ” T-shirt at the dingy bar of the Swagman Attic Inn, where conversation centres on a recent gunfight between local Baguio gangs keen for the rights to sell fried chicken at the bus station.

A sign above the bar reads, “Alcohol is the greatest enemy of man. But the Bible tells us to love our enemy”. Johnny Cash singing The Beast in Me on the television adds to the frontier atmosphere.

“Only foreigners believe in psychic surgery. It’s voodoo medicine,” adds Tony.

Taxi driver Abe, meanwhile, says he has seen Labo’s men buying cuts of meat in the market that “the poor would not eat”.

Felix, whose business card proclaims him to be a “master butcher”, tells his friends to shut up. “Labo is a very powerful man,” he advises with menace. “Be careful what you say.”

When Labo arrives for dinner with his glamorous, twenty-something Russian girlfriend — a leggy, ice-blond Brigitte Nielson lookalike — on his arm, Felix leaps from his chair to shake Labo’s hand. Abe and Tony sacrifice their San Miguel beers to dart off into the stormy night.

A greasy-haired man in a cheap anorak hugs Labo like a long lost brother. “Thank God that you have come home to us,” he fawns, recalling the healer’s Moscow troubles. The barmaid tells me later that the man is a senior figure at the Bureau of Internal Revenue.

BELIEF IN PSYCHIC surgery is strongest at the extremes of the Philippines’ massive wealth gap. The indigenous poor receive free treatment from the faith healers, who appear to remove tinfoil, coins, stones, bamboo, even dead insects and chickens’ feet from their bodies in line with a belief in witchcraft.

Labo, however, has given up on the destitute. He says they steal watches and wallets from his richer patients, who indulge in psychic surgery simply because they can afford to. But the big money comes from treating foreigners.

The first documented case of psychic surgery was performed in the 1940s, by Eleuterio Terte from Pangasinan province, west of Baguio. It became an international industry in the late 1960s under Tony Agpao, the father of assembly-line psychic surgery whose travel agency flew in charter planes of patients from Europe, North America, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. They slept and dined and spent their money in his wife’s hotel.

In the 1970s, Agpao — who, when he got sick himself, had his appendix removed in a San Francisco hospital — boasted that he was personally responsible for 30 per cent of all the region’s foreign-currency earnings.

Followers of Agpao say the strain of channeling the Holy Spirit resulted in his early death at the age of 42 — in 1982, of a stroke while cruising in his Mercedes. Labo quickly took over the wheel, carving out a healing empire like Baguio had never known.

The son of a psychic dentist (whose magic touch, it was said, could fill cavities, mend rotten teeth and even promote the growth of a new set of gnashers in the elderly), Labo had married a Japanese patient, Yuko Narakawa, in 1980 (they separated in 1998). The glamorous duo became Baguio’s first couple when Labo entered politics in 1984, effortlessly buying the support of the poor with free rice.

Soon Narakawa was also performing psychic surgery under her husband’s guidance, and the couple quickly cornered the lucrative Japanese and Korean markets and played key roles in promotional documentaries on psychic surgery shown across the world. The Marcos connection boosted their money-making potential at home.

Other healers suffered financially from the Labos’ success, including “the Reverend” Placido Palitayan. The Swagman’s barmaid points out one of Palitayan’s patients — a skinny, fifty-something Australian hippy with a shock of curly grey hair and kidney stones — sitting alone in the corner of the restaurant sipping iced water. “No way am I talking to you, man,” he says, more than a little terrified. “You’re giving off an awful lot of negative energy.”

TWO KILOMETRES out of town on the Marcos Highway, Palitayan’s surgery is a small, concrete lock-up opposite Holy Trinity Construction Supplies. He is a stunted, tired-looking 57-year-old in a San Francisco 49ers cap, aviator shades and baggy dad jeans. A patient is waiting, so he yanks open the rusting iron doors to reveal bare walls painted soft pink. Palitayan’s scruffy assistant brushes away the flies and a patient edges onto the blood-stained operating table.

Eyes closed, Palitayan places his right hand an inch above her forehead and concentrates hard for about 20 seconds. What he calls “magnetic healing” complete, he shifts his chipolata fingers to her lower abdomen. Blood appears with an audible “pop” and his hands become flecked with scraps of black tissue. “Infected uterus,” he offers casually, flicking the gunk towards a plastic bucket. He misses and it sticks to the wall with a splat.

In his glory days of the late 1970s and early ’80s, Palitayan says her treated 100 foreigners a day, including tennis player Ivan Lendl for muscle strain and actor Peter Sellers for a heart ailment

Palitayan rinses his hands in a bowl of bloody water and we head next door to his son’s truck-stop cafe. Placido III is preparing pinicpikan, a local dish. The main ingredient is chicken scorched in an open fire. But first, the live foul is tethered and slowly clubbed to death, ensuring that every inch of the chicken’s flesh is saturated with adrenalin-loaded blood when the it finally succumbs to the drawn-out beating and dies. “Compassion is the secret of healing,” says Palitayan. “Not money, big cars and fancy clothes.”

In his glory days of the late 1970s and early ’80s, Palitayan says her treated 100 foreigners a day, including tennis player Ivan Lendl for muscle strain and, in his Manila hotel, actor Peter Sellers for a heart ailment. Sellers died of a heart attack in 1980.

A messy divorce (“she took all my money”) and problems with gambling and booze have succeeded in slashing Palitayan’s business to just five foreigners a month, he says. More than a little bitter, he is frank about the mechanics of the profitable psychic healing industry. Like Labo, Palitayan has had run-ins with the authorities. In 1989, he was arrested in Spokane, Washington, for practising medicine without a licence. After 20 hours of questioning, he says, he was released without charge.

In 1992 he was refused entry to Hong Kong, where he was to hold a week-long healing tour. During his five hours at the airport, he discovered that his sponsor — an American entrepreneur who had promised to split each US$200 fee per patient with the healer — was charging US$400 and ripping him off.

“He was a fool,” Palitayan says. “If he was wise, he would’ve brought patients to me. He would not have advertised. That’s what I need — a partner who is sensible. We could make good money … silently.”

Contrarily, perhaps assuming all publicity is good publicity, Palitayan keeps a cutting of the incident from Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post in his wallet. The headline reads, “Psychic Healer Fails To Soothe Hong Kong Immigration”.

DOWN THE YEARS, most psychic surgeons have been discredited. Back in 1967, Agpao was indicted for fraud in the US, forfeiting a US$25,000 bond when he jumped bail and fled back to the Philippines. In 1986, Manila-based Gary Magno was arrested in Phoenix for the fraudulent practice of medicine after he was found with a plastic pouch of blood and offal in his trouser waistband. He also skipped bail.

These days, Palitayan has a new goal. “To save the world,” he says, with all the excitement of a reluctant retiree anticipating a dotage pottering in his garden. Palitayan will do this through “supernatural consciousness” and his Galacayan Evangelical Mission for World Peace.

His mission statement reads: “There is no exit and no place to hide or escape if nuclear war will broke out, for it is written in the Bible that even though you escape in outerspace, hide in deep bunkers or flee to the bottom of the sea you will still die eventually. This prophecy has been fulfilled thousand years ago, for scientist build mansion in outer space aside from space station. They also establish a city under the bottom of the sea near Japan.”

A Japanese patient told him about the submarine extension of Tokyo. “It’s finished and ready,” Palitayan says, wet lips quivering. “There’s no time to waste.” He adds that another patient, whom he calls a high-ranking US military officer, also shared his secrets about “the button”.

“It’s a big red button,” Palitayan whispers. “And my friend can press it and kill us all. Nobody knows this, not even his own mother.” He winks conspiratorially. “But I know.”

Even so, Palitayan still travels to the US every few months on three-week healing tours to boost his meagre income at home. He treats 20 patients a day, each paying US$75, and avoids the police by performing psychic surgery only “behind closed doors if patients insist”.

Most psychic surgeons in the Philippines, however, prefer their patients to visit them in the Southeast Asian country, where lax laws allow them to practise with impunity. To do this, they utilise the help of overseas agents who promote their work and organise tour groups. These agents normally take the form of new-age stores, alternative healing centres and off-the-wall religious groups.

ROBERT AND MARY Skillman of the Spirit Revisited Seminary in Vallejo, California, first met Labo in March 1990. Since then, the chirpy couple have visited twice a year, introducing 500 paying visitors to the man they call “Godfather”.

“I have so much respect for him,” gushes Mary, whose advertised skills include the “laying on of hands” and teaching Brazilian samba. “Even in the face of so many attacks on his powers, his energy and faith are tremendous.”

She recalls seeing Labo work his magic on a German toddler with deformed legs. “It took Jun Labo just two weeks before she walked for the first time in her life. It was truly a miracle.”

Though Labo was best man at their 1992 wedding in the Philippines, he has never visited the Skillmans in the US. “We want to take him to Disneyland,” says Mary. “He would love it there.”

In the UK, Patrick Hamouy of Alternative Therapies in Gerrards Cross, in Buckinghamshire, uses the Internet to promote “ultimate healing courses” in Baguio under the tutelage of Palitayan’s 59-year-old cousin, “Brother” Laurence Cacteng. According to his website, Hamouy “has studied psychic surgery in depth since May 1997 … His understanding of healing is second to none”.

Priced at £1,950, the two-week courses, according to promotional materials, include therapeutic singing sessions and discussions on the healing powers of angels and archangels, stones, clay, urine and ants.

Hamouy also sponsors Cacteng’s trips to the UK and France. He has introduced more than 100 patients in the past two years, he says, but last year (1998) he had the British health authorities on his back. “I explained, there is no actual surgery in the normal sense,” says Hamouy. “No anaesthesia, no instruments, no cutting. They wrote back and said, ‘Okay, but just make sure his fingernails are clean.'”

A YOUTHFUL 59-YEAR-old with a pudding-bowl haircut and the pliant face of a chuffed pixie, Cacteng lives in a comfortable detached house in a leafy Baguio suburb. The neighbours’ apple-cheeked kids play ball in the garden.

Sitting at his desk under the healer’s all-important print of Christ, he ushers me in with a wide smile, and he immediately disagrees with Palitayan’s patient with the kidney stones — Cacteng says my vibrations are good and I have a “nice aura”.

Against the wall sits a slate-grey sheet-metal transformer box with two steel plates attached by wires. Cacteng sits me down, places my hands on the plates and cranks up the bakelite dial. As he passes his hand over my ear, a low metallic moan is generated. He pokes a screwdriver into my arms, legs, chest and head. The small bulb in the handle lights up every time. “That’s good,” he says. “No problems.”

Cacteng, who has also visited Switzerland, Germany, South Africa and Australia as a healer, has no fixed prices, preferring patients to “pay from the heart”. Rare Japanese patients are the most generous, he says, splashing out US$50 per treatment four times a day. The French and British might fork out US$300 a week. Poor Filipino’s get away with a chicken in lieu.

As well as psychic surgery, Cacteng offers a wide portfolio of healing techniques. He recalls an Italian patient with breast cancer. “I prayed for her and told her to drink her own urine,” he says. “That fixed her very well.” Cacteng will even offer fatherly advise, as he did with Parisian teenager depressed at being dumped by his girlfriend. “I told the boy, if you kill yourself, she will laugh at you. So don’t kill yourself.”

From his desk drawer he pulls out the secret of “water therapy”. It is a rubber hot-water bottle. Cacteng also shows me a photograph of a patient undergoing water therapy. It shows a grinning Frenchman with a hot-water bottle balanced on his head.

WITH HIS HEAD held high, marching across the lobby of the five-star Makati Shangri-la Hotel in Manila’s high-rise financial district, tall and groomed 38-year-old George Nava True II towers above his compatriots. With his slick-backed quiff, tangerine polo shirt and pressed black slacks, the self-styled “Filipino Quackbuster” has made it his life’s mission to expose “alternative healers, psychics and other quacks” as dangerous charlatans. He grabs a table in the non-smoking section.

“Blame Burt Lancaster,” Nava True chuckles, explaining that Kaufman’s pilgrimage to Labo was prompted by Psychic Phenomena: Exploring the Unknown, a 90-minute documentary of sorts narrated by the Hollywood star. First broadcast across the US in October 1977 and viewed by 28 million people, the programme has been repeated on TV many times since.

Born of an English father and Filipina mother, Nava True is the grandson of the late Jose Ma Nava, one of the Philippines’ most revered union leaders and editor of La Prensa Libre, a newspaper sympathetic to the plight of the poor. He is also founder of the Health Frontiers Centre for Quackery Control, established in 1983 to expose useless health products and dangerous alternative therapies.

Health Frontiers’ mission statement kicks off with a humorous line — “We should have our minds open, but not so open that our brains fall out” — but Nava True is angry. “These healers can be killers,” he spits. “Sick people give up good treatment that might save their lives to travel halfway across the world to see these quacks. When they get home, it’s too late. They die.”

So why does the government do nothing to protect such patients? Nava True says authorities might be pleased that dying patients visit the Philippines to spend the last of their money and boost the economy. He also suggests the ghost of Marcos, a believer in all things paranormal, still has some influence on policy. “There is no government agency investigating these people,” he says. “And the health authorities have no authority. They can only act if people complain. And how can patients complain when they are dead.”

“In the US, the Federal Trade Commission has practically banned psychic surgery, but the healers get around the law by establishing their own churches and missions”

George Nava True II, the ‘Filipino Quackbuster’

Dr Gil Fernandez, secretary general of the Philippine Medical Association, agrees. “The laws in the Philippines leave us helpless,” he says, speaking by phone. “We believe many psychic surgeons are tricking people, but patients never complain. Either they are ashamed that they have been made fools of, or they have died. Until they do complain, we can do nothing.”

Nava True adds that healers also enjoy plenty of freedom to dupe patients when on tour. “In the US, the Federal Trade Commission has practically banned psychic surgery, but the healers get around the law by establishing their own churches and missions,” he says. “Once they have assumed titles, like brother and reverend, they claim the right of religious freedom and the authorities can’t touch them.”

Surprisingly, Nava True says faith healers are not necessarily wicked people, and that they might actually believe they are providing a genuine service. “They call it ‘true believer syndrome’,” he says. “Some healers have been practising for so long, they really do believe they have the power of God. Perhaps they are the ones that need help. If any of them are interested, I would recommend a good psychiatrist.”

With much work to do, the Quackbuster says goodbye to rush back to his office, leaving behind several press cuttings from Filipino newspapers. The most bizarre is from the tabloid Tempo. Under the headline, “I Am God — Faith Healer Kills Patient, Then Tries To Resurrect Her”, it tells of how in 1992 spiritualist Natividad Sequito murdered a mentally retarded woman while exorcising an evil spirit. She did this by ramming a 30cm length of wood down the 20-year-old’s throat and smashing her over the head with an iron padlock.

Burt Lancaster appears in 'Psychic Phenomena: Exploring the Unknown', the 1977 television special that Nava True says introduced the Philippines' psychic surgeons to a lucrative audience in the West. Video: Patrick Hamouy/YouTube

NAVA TRUE SAYS he detests the new-age travel agents that “make a living from suffering”. He also berates the makers of sensational infotainment TV programmes and writers of books on the paranormal. He says they perpetuate the “fake healing” industry and reap the secondary financial rewards “like scavenging fish around the jaws of man-eating sharks”.

Speaking on the phone from his Los Angeles office, Alan Neuman, of Alan Neuman Productions, maker of the Lancaster-narrated Psychic Phenomena, snaps back. “Labo is 100 per cent genuine,” he says. “I’ve been filming his work for over 20 years. You must understand, the healers are working in another dimension. Just because it is possible to replicate what they are doing with sleight of hand, does not mean that is what they are doing.”

But Nava True’s number-one nemesis is Labo’s biographer, Jaime Licauco, who is also author of the books Understanding the Psychic Powers of Man; The Truth Behind Faith Healing in the Philippines and The Magicians of God. As president of the Inner Mind Development Institute, Licauco — who holds a masters degree in business management — runs workshops in telepathy, telekinesis, spoon bending and what he calls other “advanced mind dynamics”. His two-day Basic Intuition and ESP Development course costs 4,000 pesos (US$100) per person.

An animated, balding 59-year-old wearing a crystal pyramid pendant, Licauco says Filipinos are descendants of Lemuria, or Mu, a mythical civilisation that supposedly existed long before Atlantis somewhere in the Pacific. To avoid hungry dinosaurs, it is said the Lemurians lived underground, growing crops with the aid of crystal-powered light generators.

“As a result,” Licauco writes in The Truth, “[Filipinos’] vibrations are higher and they are able to reach a heightened state of awareness faster and more easily than other people.”

“We had no intention of catching Labo in the act. We only noticed something irregular with the footage back in the studio. We slowed the tape down, but we never reversed it”

Jessica Soho, producer of TV news magazine programme ‘Brigada Siete’

Licauco’s Manila office is decorated with images of Egypt, a country that, he says, he has visited “not only in this lifetime”.

When visiting the UK, he continues, he was cured of a common cold picked up at Stonehenge by veteran British faith healer Stephen Turoff. This was achieved, Licauco insists, by Turoff pushing a five-inch blade up his nose. A framed photograph of the author meeting Pope John Paul II takes pride of place over his busy desk.

“I’m not defending the healers,” says Licauco, who claims Labo removed cysts from his wife’s breast. “I am defending the truth.” But even he confirms that some healers resort to trickery occasionally, when their powers have been weakened by working too hard. They do this, he adds, to ensure their patients are not disappointed.

But the crux of Licauco’s argument is that psychic surgery is a paranormal phenomenon beyond logic and science. When animal blood is discovered at a scene of psychic surgery, he says the healers cannot explain how or why. In short, he argues, the Lord works in mysterious ways. “The blood doesn’t come from the patient’s body. It is materialised by the Holy Spirit,” he says.

Licauco also insists he is not paid by the faith healers, and they do not sponsor his shameless hagiographies. But they do give him “gifts”, he says.

He argues that Nava True and other sceptics manufacture evidence to discredit psychic surgeons. To illustrate his point, he slips a tape of investigative TV news magazine Brigada Siete into the VCR. During the programme, aired while Labo was incarcerated in Moscow, an allegedly cheating Labo is revealed collecting a large chunk of bloody flesh from beneath his operating table.

“There. Can you see?” Licauco cries. “Labo wasn’t bringing his hand towards the patient. He was taking it away. They reversed the film.”

Jessica Soho, Brigada Siete producer — and a Catholic believer in faith healing — denies Licauco’s “ludicrous” accusation. “We had no intention of catching Labo in the act,” she says, laughing, when called. “We only noticed something irregular with the footage back in the studio. We slowed the tape down, but we never reversed it.”

BACK IN BAGUIO, Labo’s guards have put down their guns and are listening to a religious crusade on the radio.

“Are you happy?” the fire-and-brimstone preacher rants through the static. “Then sing praise, sing praise to God Almighty. Are you sick? Then call, call today on the messenger of the Lord. If you believe, if you believe, then you will be cured. And your sins will be forgiven.”

Labo is praying in his chapel. Lost in a trance in front of a weeping bust of Christ, he is performing paranormal house calls, he tells me later, or “distance healing”. He does this by concentrating his “third eye” on the yellowing photographs that decorate the altar — of a sweet, weak old lady balancing on crutches; of an emaciated grey-haired man in a wheelchair; of a sad-eyed teenager with no hair, no eyebrows.

Labo then astrally projects himself, or so he claims, across the oceans to check on their progress.

Finally, sticking to Journalism 101’s tried-and-tested tactic of saving the most insulting question until last, it is suggested to Labo that his big house, his luxury cars and his expensive jewellery may have been purchased by cruelly ripping off desperate people clinging to a last remaining hope of staying alive.

“The people who criticise me don’t believe in God,” he says, casually lighting another Marlboro Menthol with a disposable lighter. On one side, the lighter features a buxom blonde in a bikini. On the other, the words “Jun Labo for Mayor”.

“But they will believe when they are dying. They will pray too. They will come to me.”

With our meeting over, Labo bids a kindly “God bless”and offers a gift, a promotional Japanese videotape entitled Jun Labo — The Only Choice. Watched later, one scene has Labo demonstrating the need for psychic-surgery patients to have an open mind. He does this by twirling a small square of cotton into a thin strand, which he then carefully threads into a middle-aged woman’s left ear. Abracadabra … and he pulls it out of her right ear.

CLEAN-LIVING KAUFMAN also had an unusual way of flossing. After a few days submerged in his depraved comic creation and alter-ego Tony Clifton — a hard-drinking, chain-smoking, whore-hopping Vegas lounge singer — Kaufman would attempt to cleanse his system by swallowing 15 metres of damp cheesecloth. Through a process of controlled peristalsis, he would then pass the fabric through his alimentary canal and out of his backside.

Kaufman’s short life was full of bizarre behaviour and practical jokes. He grappled with women in inter-gender wrestling matches. He took his entire audience at Carnegie Hall out for milk and cookies. He was Elvis’s favourite Elvis impersonator.

Today, die-hard fans hope — even pray — that Kaufman faked his death, that his last-gasp trek to Baguio was just an elaborate twist in a great if morbid hoax. Though a sign at the Nagoya Inn’s exit reads, “Thank You, Come Again”, Labo has not seen Kaufman — or any more of his cash — in 15 years. Not since the comic left the Philippines mountain town thousands of dollars lighter, still dying of lung cancer. ◉

This long-form feature is a little long in the tooth. It was timed for the release of Man on the Moon in 1999, and ran over seven pages in the British edition of GQ, as well as in Max in Spain and Post Magazine in Hong Kong.

SHARE