Oscar Wilde's 'holiest place in Rome' is the final resting place of romantic poets Keats and Shelley, as well as the author of 'The World of Suzie Wong' and a sexpot actress who angered the Pope.

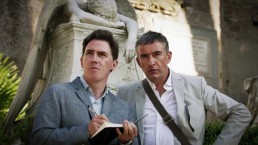

LOW-BUDGET MOVIE The Trip to Italy was an unlikely indie sleeper hit this year, largely thanks to its two stars’ quick-fire impersonations of Michael Caine, Al Pacino, Anthony Hopkins and other silver-screen notables.

The mockumentary’s central conceit sees semi-fictionalised versions of British comics Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon flaunting their skills for mimicry while on a road trip of the culture-rich Mediterranean nation.

Along the way, Coogan and Brydon retrace the “Grand Tour” steps of English Romantic poets of the early 19th-century, so when they get to Rome it’s a given that the funny men will steer their Mini Cooper — a nod to Caine’s 1969 caper The Italian Job — towards the Eternal City’s Cimitero Acattolico, its “Non-Catholic Cemetery”.

NICKNAMED THE “ENGLISH Cemetery” and one of Rome’s most fascinating yet off-beat attractions, the Cimitero Acattolico dates back to the early 18th century, when Pope Clement XI allowed England’s Stuart court in exile to bury its dead on a patch of wasteland. Over time it became final resting place of Protestants, Buddhists, Confucians, Jews, Zoroastrians and non-believers from across the world. It’s arguably the most beautiful boneyard on the planet.

The Trip to Italy in its movie form is an abridgement of a six-part, three-hour BBC television series, but they still had 108 minutes to play with. Why, then, do Coogan and Brydon not visit the cimitero’s most revered poet in residence?

And how, when wandering among its graves, do they miss godsend opportunities to impersonate hell-raising thespian Peter O’Toole, Britain’s buffoon of the bawdy Benny Hill and the mighty Orson Welles?

INSULATED FROM SNARLY traffic by a soundproofing section of the Aurelian Walls that were thrown up between 271AD and 275AD to enclose the seven hills of ancient Rome, the Cimitero Acattolico is serene and sylvan. Birdsong wafts from its cypress, umbrella-pine and pomegranate trees, manicured hedges fringe lovely gardens of roses, hydrangeas and azaleas, and daisies speckle the lawns.

Though the cemetery is twitching with life, it’s the dead that attract visitors. The burial ground is packed with perished painters, sculptors, philosophers, actors and authors — testament to the pull that Rome has long exerted on creative types. Inscriptions on tombs can be found in English, Chinese, French, German, Lithuanian, Russian, Greek, Bulgarian, Japanese and other languages.

“The cemetery is an open space among the ruins, covered in winter with violets and daisies. It might make one in love with death, to think that one should be buried in so sweet a place”

Percy Bysshe Shelley

On entering the cemetery in The Trip to Italy, Brydon recites Percy Bysshe Shelley (in the orotund voice of Hopkins, to spiky Coogan’s annoyance) and the duo climb the terraced plots to where that poet’s ashes were inurned after he drowned off Tuscany in 1822, at the age of 29. Shelley’s modest gravestone bears lines from Shakespeare’s The Tempest: “Nothing of him that doth fade/But doth suffer a sea-change/Into something rich and strange.”

The words quoted by Brydon, however, are from Shelley’s Adonais: An Elegy on the Death of John Keats, whose grave is a shrine to cemetery visitors, but which The Trip to Italy strangely avoids.

That memorial to Keats, who succumbed to tuberculosis at the age of 25, just four months after arriving in Italy in 1821, does not bear his name, simply stating, “This Grave contains all that was Mortal of a YOUNG ENGLISH POET.” It also features a couplet chosen by Keats, who considered himself a failed wordsmith and so not worth remembering: “Here lies One/Whose Name was writ in Water.”

MANY THOUGHT OTHERWISE, of course. Ruminating on Keats’ final resting place before his own passing, Shelley wrote, “The cemetery is an open space among the ruins, covered in winter with violets and daisies. It might make one in love with death, to think that one should be buried in so sweet a place.”

Oscar Wilde, who travelled to Italy as a young man in 1877, shunned the Vatican to declare Keats’s gravesite “the holiest place in Rome”.

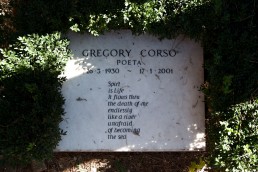

It’s certainly one of the Italian capital’s most quirky diversions, and likely that Coogan and Brydon would have explored. If so they might have stumbled upon the grave of Gregory Corso (1930-2001), youngest of the Beat Generation writers of the 1950s that included Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg.

Just steps away rests English actress Belinda Lee (1935-1961), who performed alongside comi-salacious Hill. Typecast in her brief career as a sex kitten, Lee’s torrid affair with a Roman aristocrat caused such a scandal that the Pope intervened.

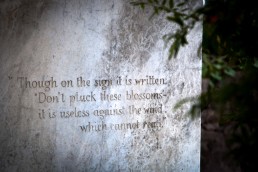

Long-time Rome resident Richard Mason (1919-1997), British author of The World of Suzie Wong, is also buried here. His grave is inscribed with words from a go-with-the-flow Japanese proverb: “Though on the sign it is written: ‘Don’t pluck these blossoms’ — it is useless again the wind, which cannot read.”

THEN THERE ARE the two airmen who bought the farm when their plane clipped a tree at Rome Aerodrome in 1919. One of their passengers, bound for Cairo, was TE Lawrence, who survived with a fractured shoulder and cracked ribs. O’Toole later played the starring role in David Lean’s 1962 epic Lawrence of Arabia.

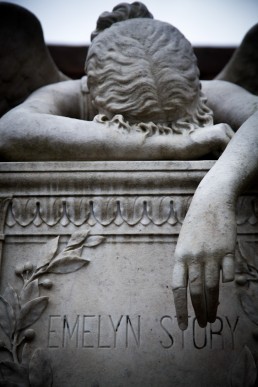

And when Coogan and Brydon pose for photos in the Cimitero Acattolico, they do so in front of one of its most haunting graves: that of American Emelyn Story, who popped her clogs in 1895 at the age of 74. The Angel Of Grief that dominates the burial chamber was designed by her husband, sculptor William W Story.

The couple’s apartment in Rome’s chic Palazzo Barberini had been unofficial clubhouse for overseas writers, musicians and artists in the second half of the 19th century, and is recalled in Henry James’s 1903 biography William Wetmore Story and His Friends.

Finally, when The Trip to Italy crew packed up cameras to head home, they would have passed the grave of Generale Nicola Chiari. Little is known of Chiari (1922-1998), who is believed to have been a customs officer from Naples.

He was likely a classic-movie buff, too, with an irrepressible sense of fun. The inscription on Chiari’s headstone is a last-gasp salute to Welles’s 1941 masterpiece Citizen Kane. It reads, “ROSEBUD. WHAT DOES THAT MEAN?” ◉

This travel story ran in Post Magazine in 2014, following up The Trip to Italy. Download PDF.

SHARE