Bangkok-based American lawyer Craig Wilson is also an amateur boxer who routinely fights opponents half his age. Dubbed Farang Ba — or 'Crazy White Foreigner' — by his Thai fans, his greatest challenge was fought outside the ring.

THE SUN HAS SET over the Buddhist temple fair in Prathai, a rural village in the northeast of Thailand. Cinnamon-cloaked monks have chanted their blessings. Water buffalo rest beside rice paddies and children hunch over their textbooks, barely illuminated under the naked but low-watt bulbs of street stalls selling dried-squid snacks and sugarcane juice.

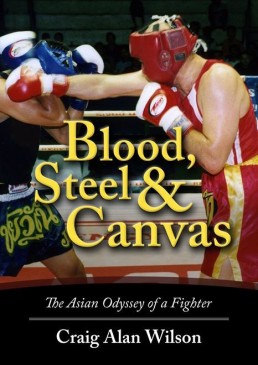

Now comes the highlight of the day’s festivities: an open-air boxing match to be fought by Queensbury rules. In the blue corner, proud and sculpted Thai fighter Pumin Sorjaturong. In the red, conspicuous and ill-at-ease American Craig Wilson.

Tension is palpable; betting feverish. The bell rings for round one and cheers overwhelm the electric hum of the tropical night’s cicadas.

A flurry of jabs, a lightning hook and Sorjaturong stumbles to whoops and jeers. The 26-year-old knows the American is capable of the unexpected. He met Wilson in the ring at the Thai king’s birthday celebrations in December. On that auspicious day in Bangkok, 5,000 revellers witnessed Sorjaturong’s humiliating knockout at the end of a short right to the jaw in the third round.

As the fighters square up once more, spotlights catch Thai script printed in gold across the American’s trunks. It proclaims him to be “Farang Ba”, the “Crazy White Foreigner”. Those trunks hide the 48-year-old’s colostomy bag.

WILSON IS A MAN of startling contradictions. As the only foreigner on Thailand’s amateur boxing circuit, he relishes going toe-to-toe with peak-fitness fighters half his age, and yet he offers cash incentives to Bangkok motorbike-taxi drivers to be especially careful when transporting him to his plush office in a high-rise tower.

As general counsel with Bangkok-based merchant bank Finansa, he arrives to work in regulation pinstripes, spectacles and Gordon Gekko suspenders, and yet the balding, near-sighted lawyer can greet a Monday morning with a black eye, a fat lip or facial stitches.

“I’m an in-house lawyer,” laughs Wilson, who smiles readily but takes his obsession seriously. “I rarely meet clients myself so the bruises and cuts are not a problem. Some of the staff roll their eyes and probably think I’m insane. But they know how important boxing is to me. They respect what I do.”

And Wilson surely deserves respect, for his is an inspirational tale of a man who has rolled with life’s cruellest punches. Though he had his entire colon surgically removed in 1996 after a bout with cancer, Wilson has refused to go down.

“I began to react to these unsettling intrusions on my well-ordered existence. Within a few weeks, I knew that I had escaped from my rut”

Lawyer and boxer Craig Wilson

THE SUBJECT OF a feature-length documentary by New York-based filmmaker and fellow boxer John Sullivan, Wilson was raised in suburban Washington DC in a comfortable middle-class family. He was, he says, an academic whizz-kid but also “a wimp”.

“I was an okay sprinter,” he shrugs, “but contact sports? Forget it. I wasn’t really into exercising or getting hurt. My head was deep into books.”

Majoring in history at Yale, Wilson progressed to law school at Harvard, graduating in 1981 and taking the first steps on a lucrative — and what should have been run-of-the-mill — legal career. He became a law clerk for a federal judge on the US court of appeals in Houston, Texas, before moving into corporate law with international legal giant White & Case in DC. What Wilson gleefully describes as his “slow but steady slide into pugilism” began in 1987.

Frustrated that the far-flung corners of globe and their potential for adventures were eluding him, Wilson snapped up a posting with the Asian Development Bank in the Philippines’ capital of Manila. His unavoidable exposure to that nation’s poverty, and its good-natured people’s resilience, quickly opened Wilson’s eyes.

“I began to react to these unsettling intrusions on my well-ordered existence,” he says. “Within a few weeks, I knew that I had escaped from my rut.”

An out-of-shape 85kg “with very little muscle” at the time, Wilson resolved to maintain a healthy distance from other well-heeled expatriates in Manila, their sheltered existence revolving around guarded living compounds, chauffeured commutes to work and poolside buffets on weekends at private recreational clubs. The death of his father, just months after his overseas posting, added to his conviction.

“My dad died of a heart attack, and being overweight was certainly part of the problem. I did some soul searching. I was 31. My life was sedentary, too comfortable. I looked in the mirror and said to myself, ‘It could happen to you, too, so easily.’”

TWO MONTHS LATER, Wilson discovered an unlikely saviour in the down-and-dirty Elorde Sports Centre in a ramshackle Manila suburb. The rundown gym had been a labour of love for the late Gabriel “Flash” Elorde, who collected bantamweight, featherweight and lightweight world titles during an illustrious career spanning the 1950s and ’60s. There, he met Flash’s son, Gabriel “Bebot” Elorde Junior.

“That guy could sell rice to a farmer,” laughs Wilson. “I told him, ‘Hey, I’m a lawyer, I wear glasses.’ But I looked around and saw all these guys with incredible physiques and I said, ‘That’s what I want to look like.'”

Wilson immediately started training. Weights, ropes and sit-ups came first. Soon he was punching bag and the excess pounds fell away. The workouts continued for several months until it was time to try his hand at sparring. “I still remember the first time,” Wilson says, recalling how he sheepishly pulled on the tattered, 16-ounce sparring gloves. “I’d never been in a fight in my life, but I didn’t want the guys to think I was chicken.”

The lawyer’s lack of technique showed and his opponents toyed with him. As he progressed, however, one or two friendly punches made their way to his gut. More weeks passed and Wilson found himself being taken — and hit — more seriously until, after one especially fierce sparring round, his trainer wiped his face with a white towel, which was then stained with crimson.

“‘You have a bloody nose,’ he said. ‘Do you want to stop?’ I was genuinely angry. ‘No way,’ I replied, ‘I want to give him a bloody nose.'”

Wilson had become a fighter.

IN APRIL 1988, at an age when most would be hanging up their gloves, 75kg Wilson began to fight as an amateur in the middleweight class, winning his first bout in the Manila slum known as Tondo. He was hooked. “I think it may have been the happiest moment of my life,” he says. “I felt I’d proved something to myself, something that all the academic achievements had never given me.”

During his four years in the Philippines, the lawyer fought 22 bouts, including two in the Philippine National Games — “the officials conveniently looking the other way when the subject of my nationality arose” — and once at Araneta Coliseum, venue of 1975’s “Thrilla in Manila” between Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali.

A local sportswriter informed Wilson that he had been the first American to fight at Araneta since that legendary bout, making it a highlight in the lawyer’s boxing career. When he returned to the US in the early 1990s, however, the most exhausting and brutal fight of his life was just seconds out.

Trailer for John Sullivan's documentary 'Farang Ba'. Video: Naked Emperor Film/YouTube

IN 1993, WILSON was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, an incurable bowel condition characterised by inflammation and ulcers in the lining of the colon. Though not fighting at the time, he kept his condition in check and continued to train before being assigned to Bangkok in his new role with a New York City law the following year.

“I was living out of a hotel room, not eating regularly, too much spicy food,” says Wilson. “Things started to get out of control.”

The problem peaked in November 1995 when Wilson was forced to visit the washroom 24 times in a day. On his hurried return to Washington it was discovered he was suffering from cancer. It would be necessary for his entire colon to be removed. Wilson underwent surgery on January 31, 1996, followed by chemotherapy and radiation treatments.

An ileostomy (a surgical procedure bringing the ileum — the last portion of the small intestine — to the abdominal surface) means he will carry a colostomy pouch for the rest of his life.

“As long as there are no below-belt punches, I’m fine. I wear a foul protector beneath my trunks and that fits over and holds the colostomy pouch in place”

Wilson

After the trauma of the surgery, Wilson set himself the goal of running a marathon. The following year he finished the New York City race in under five hours. But he missed the camaraderie of boxing and soon began training. “As long as there are no below-belt punches, I’m fine,” he says. “I wear a foul protector beneath my trunks and that fits over and holds the colostomy pouch in place.”

With Asia in his veins, Wilson returned to Bangkok as general counsel for Coca-Cola in the region in 1998, only to see his job downsized months later. “I was at my lowest ebb,” he says. To keep his protégé from sinking into despair, Wilson’s burly Thai trainer Decha Boonkamnerd — a former boxer in the Thai national team — organised his first post-cancer bout. Wilson won.

“This may sound corny,” says Wilson, “but the excitement and elation kept me going while things were so tough in my professional life.”

Since then, Farang Ba has fought more than 35 times in Thailand. Last year he sparred with Olympic light-middleweight bronze medallist Pornchai Thongburan. Wilson took the eight count three times. “I was way out of my league,” he laughs.

“That’s the thing about Craig,” says Sullivan, whose documentary takes its title from the words adorning Wilson’s boxing trunks. Farang Ba: Crazy White Foreigner has been shown at 15 film festivals around the world. “He’s such a lovely, humble man. Boxers and boxing are frequently portrayed in such an unflattering light, and yet here you have this kind and dedicated guy … He is the perfect ambassador.”

WILSON GUZZLES DIET-Pepsi (“Never Coke,” he says, holding a grudge) by the caseload when training. The only dietary side effect of the ileostomy is that he can no longer eat popcorn. The kernels cannot be digested and will block the tiny opening in his intestinal wall that links his digestive system to the colostomy pouch.

“I’m not a health-food fanatic but since the surgery I’ve made an effort to eat well. That means lots of fruit and fish, and relatively little meat.”

For days before a fight, Wilson avoids fried foods and concentrates on protein. The day before a bout, he overloads on carbs.

Bangkok’s heat and humidity are extreme so Wilson runs no more than five kilometres every other day in the Thai capital’s landmark Lumphini Park. His 90-minute daily boxing workout routinely involves stretching, slow and fast rope jumping, three rounds of shadow boxing, three to five rounds on punch mitts, two or three at the heavy bag, and six sets of 50 sit-ups. Additional focus practice picks a standard punch or movement — perhaps the uppercut or the hook — and dwells on that for a couple of rounds.

When a fight is approaching, two additional exercises are added to the programme: defence practice, in which Boonkamnerd throws punches that Wilson has to avoid or block, and “punishment”, whereby his trainer wears a glove and slugs the boxer three sets of 20 times in the stomach to strengthen abdominal muscles.

Once or twice before a fight, Wilson endures “sprints”: a workout Boonkamnerd picked up from the Thailand national team’s Cuban coaches.

“I stretch and jump rope before going 30 rounds, each round of 30 seconds, with only 10 seconds between each round, of full, fast, all-out, nonstop workout: five rounds of shadow, 10 rounds on the punch mitts, 10 rounds on the heavy bag, and five rounds of fast jumping rope,” Wilson says.

“By the time that workout is over, I feel like a limp and soaking-wet rag-doll.”

ON THE MORNING of the fight in Prathai, Wilson woke early to jump rope. In the afternoon, he slow jogged for five minutes to get the blood pumping and then indulged in some relaxed shadow boxing.

But while his knowing opponent Sorjaturong saved his energy by hiding in the shade during the hot afternoon, Wilson embraced the boisterous temple-fair festivities with an ear-to-ear smile. To the joy of the villagers, he shamelessly danced with them through the dusty streets, among the scrabbling chickens and scrawny goats. He warmly shook every outstretched hand under the blazing tropical sunshine for more than two hours.

And that may have been his downfall.

Driving back to Bangkok after the fight, trainer Boonkamnerd is behind the wheel of Wilson’s silver BMW and Sorjaturong is asleep in the back. A soothing Mozart sonata plays on the CD player while Wilson fusses with an icepack, holding it to the gaping gash above his left eye that stopped the fight in the third. He will need eight stitches.

The American is quiet and contemplative. Perhaps work is a worry: it’s already 3am and gregarious Farang Ba needs to transform into a mild-mannered lawyer Craig by 8am, when he must be at his desk.

Maybe he is fondly recalling the sonic Mexican wave of surprised “ooohs” and “ahhhhs” that greeted the climax to the night’s bout, when Wilson pulled off his headgear to reveal his sweating pate — and that Farang Ba is only young at heart.

Or is he thinking about the responsibilities that come with the Sports and Martial Arts Center (SMAC), a Bangkok initiative co-owned by Wilson that gives disadvantaged Thai youngsters the opportunity to boost their self-esteem through boxing? It’s impossible to believe he might be down about the fight’s result.

“I was a great day,” bloodied but unbowed Wilson says with a sigh, as the twinkling lights of the city hove into view. “Sure, I’m disappointed. But the way I look at it, every time I climb in the ring, win or lose, it’s another nail in cancer’s coffin.” ◉

This story was commissioned in 2004 by a new US mag called Drill (an FHM/Maxim-like title aimed at the military and described as being "for men who just happen to jump out of planes or hide in foxholes for a living"). Drill was soon cancelled and the editor took my story with him to Men's Fitness. But then he left that mag, too. The disappointing outcome was that while I was paid two kill fees for the text (good), it never ran anywhere (bad).

SHARE