Britain's legendary cipher school, hidden away on the Buckinghamshire country estate where Alan Turing's genius helped cut short the Second World War, is no longer a secret.

“FILMING AT BLETCHLEY Park was amazing,” actor Benedict Cumberbatch said of his leading role in Oscar-nominated blockbuster The Imitation Game. Based on the true-life story of mathematician and computing pioneer Alan Turing, the new film recalls Britain’s race against time to decipher German military communications during World War II.

“You really feel like you’re playing slightly with ghosts.”

Secreted away on the edge of London satellite town Milton Keynes, the low-key country estate of Bletchley Park pulled in close to 200,000 visitors last year [note: 2014], buoyed by a multi-million-pound refurb and the star power of Cumberbatch and co-star Keira Knightley.

On a crisp and windless winter’s morning, however, all is placid and hushed. While the manicured lawns are inviting, their wooden picnic tables sit empty under a crystal-blue sky.

A school outing of tousle-haired children marches by in — fittingly — binary file and a lone coot weaves amongst the grey-brown rushes of the grounds’ centrepiece lake. The chimneys and oxidised-copper roof turret of the Victorian mansion house opposite, the wartime headquarters of the British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), are reflected in the dark water.

It is difficult to appreciate the magnitude of what was achieved here.

HISTORIANS HAVE ESTIMATED that the Bletchley Park codebreakers may have shortened the war by two years, possibly saving hundreds of thousands of lives.

What the estate’s duty manager, Dr Joel Greenberg, calls the “truly industrialised” level of military snooping achieved at Bletchley had been made possible by the purchase of the 22-hectare site by the Secret Intelligence Service, or MI6, for £6,000 in 1938. Here, Turing and many other tweedy, brilliant but frequently eccentric mathematicians, chess wizards and puzzle-solving prodigies would pit their wits against the most complicated coding methods ever devised.

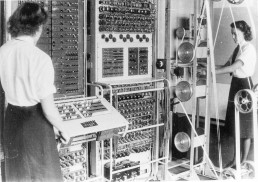

“By the end of the war, the facility employed about 10,500 people,” says Greenberg. By then the codebreakers of GC&CS were processing tens of thousands of covert Nazi messages every day. “There were 8,500 working on the site on a day-to-day basis, and several thousand at surrounding out-stations within commuting distance, all working on a three eight-hour shift system.”

Most astonishingly of all, their world-changing accomplishment remained a closely guarded secret for decades, only becoming public knowledge in the 1970s as wartime documents were gradually declassified.

All Bletchley Park staff had signed the Official Secrets Act and were not permitted to speak of their work, even after the war, Greenberg says. Winston Churchill, Britain’s wartime prime minister, called them “the geese that laid the golden eggs and never cackled”.

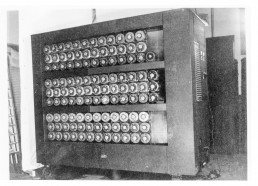

TURING’S CUMBERSOME, CLACKING and complex Bombe contraption famously helped to read messages encrypted by Germany’s Enigma cipher system, which had originally been invented at the end of World War I. By 1939 the Enigma machine had been adapted so that it could be configured in 150 million, million, million different ways (the current probability of winning first prize in the Mark Six lottery, by comparison, is 14 million to one).

And to make life even trickier, each Enigma machine was reconfigured at midnight, so any discovery made in the previous 24 hours at Bletchley was rendered useless, and every day the quest would start again.

“It was like working in a factory: they had a specific tasks to do, and the vast majority had no idea about what they were actually doing”

Bletchley Park duty manager Dr Joel Greenberg

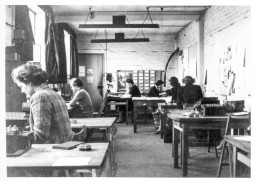

Much of the laborious and profoundly stressful intelligence-gathering — real lives were at stake and minutes counted — took place in swiftly thrown-up huts (“Glorified garden sheds,” according to Bletchley Park chief executive Iain Standen), a number of which have been restored thanks to an £8-million British National Lottery-funded grant.

With their utilitarian, no-frills interiors and bare wooden floors, the huts now look and feel as bleak as they would have done in the 1940s (I can vouch that they are mighty chilly in November). Bakelite phones, “Careless Talk” signs, double-breasted coats and fedoras hanging from racks, and overflowing ashtrays and cups of tea on desks attest to a day-to-day grind that must have been anything but glamorous.

“They were brought here for a specific job,” Greenberg says of the average wartime worker at Bletchley. Also the author of a biography of code-breaker Gordon Welchman, who made improvements to Turing’s Bombe, Greenberg says many Bletchley employees would have been ignorant of the importance of their work. “It was like working in a factory: they had a specific tasks to do, and the vast majority had no idea about what they were actually doing.”

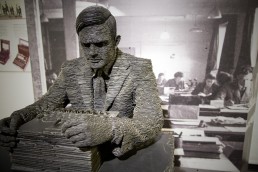

Away from the huts, Bletchley Park’s brick-built Block B houses the main collection of exhibits relating to code-breaking efforts, including the world’s only fully operational Bombe rebuild and a life-size statue of Turing — brooding over an Enigma machine — created by British sculptor Stephen Kettle from half a million stacked slithers of grey slate.

As well as German communications, Bletchley Park was also involved in Japanese code breaking. (Initially, the GC&CS’s Far East Combined Bureau, tasked with intercepting and cracking Japanese naval codes, had operated out of Hong Kong, before moving to Singapore in 1939, and further afield with the Japanese advance.)

This was originally carried out at Hut 7 at Bletchley, but in 1943 Japanese operations were heavily expanded, becoming nicknamed “the Burma Road” after the 700-mile allied supply line from China to Burma.

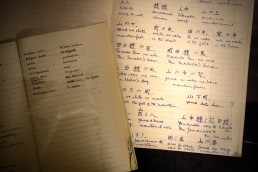

As well as a Tirpitz Enigma machine, designed for carrying messages between Germany and Japan, exhibits in Block B include Japanese-language flash cards and exercise books used by Bletchley Park staff charged with mastering basic Japanese-language skills in mere weeks, and a Japanese flag that likely belonged to a kamikaze soldier.

Messages handwritten on the flag include, “I’m sure we will win”, “Loyalty and courage”, “Let’s beat America and England” and “At least I shall kill one enemy for the emperor”.

The Imitation Game. Video: Movieclips Trailers/YouTube

ESSENTIALLY A HISTORICAL thriller-cum-biopic, The Imitation Game focuses on the troubled genius of Turing, whose short life ended tragically. Prosecuted in 1952 for homosexual acts — then still criminalised in the UK — he accepted chemical castration as an alternative to prison and died in 1954, at the age of 41, from cyanide poisoning. His death was recorded as suicide.

The full story of Bletchley, however, is the tale of thousands of diverse people, some surely brilliant and others less so. And though their day-to-day work would have been demanding, Greenberg says it was not all algebra and gloom.

At the height of their code-breaking exertions, Bletchley Park hosted its own drama group staging productions such as Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, the tennis court would have seen a steady flow of white-togged fitness fanatics, there was a popular chess club (naturally) and a billiard room, as well as a Scottish dancing society. With most staff in their early 20s, romances would have blossomed, Greenberg says, though perhaps fittingly furtively.

“To work where these people breathed, lived, loved, worked, struggled, kept secrets, were quietly, stoically heroic,” an admiring Cumberbatch concluded, “was overwhelming.” ◉

A cut-back version of this travel story ran in Post Magazine in February 2015, timed for the release of The Imitation Game. Download PDF.

SHARE