The seaside villages of the Cinque Terre are among the most photogenic in Italy. Get the selfies in the bag sharpish, saving time for hiking, snorkelling, shopping, the freshest seafood and, naturally, artisanal gelato.

FROM CHINA’S THREE Kingdoms to the Seven Hills of Rome, prefix any group of kindred landmarks with a number and something magical happens, conjuring up visions of ancient realms cloaked in wonder.

While the villages of Cinque Terre — or “Five Lands” — are likely less sensational than the Fourteen Flames of Valyria (volcanoes, apparently, in Game of Thrones), they are such clichés of what Italian fishing communities should look like as to appear otherworldly.

Dotted along the Italian Riviera, the sweeping crescent of rugged coastline in the northwest of Liguria, each seaside settlement is a higgledy-piggledy confusion of houses in weathered apricot, shell pink, marigold and other sunny colours, all contrasting pleasantly with the Ligurian Sea’s iridescent blue.

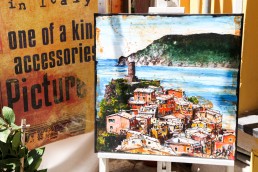

Collectively designated a Unesco World Heritage Site, the villages are the cobble-stoned stuff of chocolate boxes, of jigsaw puzzles and screensavers. And Manarola is the most ravishing of the bunch, its jumble of buildings springing from anthracite-grey rock and cascading down a steep cliff face as if in a proto-cubist Cezanne painting.

OUR EXPLORATION OF the Cinque Terre begins not in Manarola, however, but in La Spezia, the naval town immediately to the southeast. Listed in order from La Spezia, the five villages are Riomaggiore, Manarola, Corniglia, Vernazza and Monterosso al Mare, and each has its own personality and pull for the outdoors enthusiast, the foodie and the beach bum.

There is no vehicular access to quattro of the cinque (coaches can drop off within walking distance), so, as a rule, no cars inside. The centuries-tested way of moving between the settlements is via hillside walking trails that snake through gnarly vineyards and terraced lemon and olive groves, all bound by dry-stone walls.

Rowboats and kayaks crowd the slipway and a nonchalant old-timer with a greying explosion of candyfloss hair tends a skiff beneath signs for ‘boat tours’ and ‘boats for rent’ and ‘snorkelling and scuba tours’ in English and Chinese

Some trails can be closed due to rockfalls but each village — surprisingly, considering their compact size — has a railway station and the Cinque Terre Express tunnels through between La Spezia and Levanto to the north. Hops between one community and the next take about five minutes.

So, from La Spezia, our first stop is RIOMAGGIORE, which quickly gives the impression of a working fishing village, its stone slipway hemmed in by tall, slender dwellings that create a manmade canyon.

Rowboats and kayaks crowd the slipway and a nonchalant old-timer with a greying explosion of candyfloss hair tends a skiff beneath signs for “boat tours” and “boats for rent” and “snorkelling and scuba tours” in English and Chinese. His pricey Persol sunglasses suggest good business — tourism has long ousted fishing and winemaking as the primary source of income in the Cinque Terre.

Beyond the headland, Riomaggiore’s La Fossola beach is stony, small and deserted, but the day’s early birds throw down towels on a shelf of stratified black rock, thrust and tilted upwards by violent subterranean gurgling long, long ago. The youngsters launch themselves into the clear water, whooping like gibbons.

THE VIA DELL’AMORE — the “way of love”, a cliff-hugging coastal trail heading north from Riomaggiore — has been closed in recent years but hopefully will reopen for 2019. If not, go back to the train station for a short ride to MANAROLA, the topsy-turvy but postcard-perfect inspiration for a zillion Instagram moments. Many of Cinque Terre’s most alluring snapshots are of Manarola, below which boats bob in a dinky harbour.

Word has it that a house-proud fisherman once looked back to shore from such a boat and could not tell his home from the others. Deciding his abode should stand out, he painted it a distinctive colour. His idea caught on (Carlo’s house became the honey-hued one, Paolo plumped for lilac, Luca’s was a muted ginger, etc) and today’s eye-catching gallimaufry is the result.

Visit Manarola later in a day — or stay a night — and you will see the buildings change colour with the angle of the sun. As early evening turns to dusk, rose becomes coral pink and then vermillion; lemon transmutes to old gold via primrose and amber.

The coastal path is the place to capture Manarola’s best side in megapixels, but today a small crowd mills at the most photo-friendly spot: a glamorous, loved-up couple — matching in white linen, tanned as orange as oranges — hogs the site, gazing dreamily into the distance for stick-mounted iPhone selfies.

NEXT UP COMES CORNIGLIA, the cutest (population: less then 300) and least visited of the villages due its perch on a high promontory, with more than 350 steps to climb from station and jetty. Many Cinque Terre visitors bypass Corniglia completely, though it is believed to date back to Roman times and so arguably (and they do argue on this point) the most ancient of the settlements.

A treat among Corniglia’s handful of eateries is Alberto Gelateria, where the daring go for a basil-flavoured gelato. It’s an acquired taste, and the Miele di Corniglia concoction, imbued with local honey, is a sweeter and safer bet.

EARLY AFTERNOON AND VERNAZZA, by contrast, is pumping. Founded in the opening years of the 11th century as a fortified village to protect settlers from pirates, its focal point is the seafront Piazza Marconi, flanked on one side by the 14th-century Church of Santa Margherita d’Antiochia and high on the other by the 15th-century Castle Doria.

Dwellings here are grander than in the villages called upon earlier — though many have fallen into genteel disrepair — and many balconies zing with bougainvillea and jazzy geraniums.

There are also galleries, restaurants and cafes, and hole-in-wall shops fussy with artworks and ceramics, fridge magnets, handmade lemon soap, jars of pesto (the sauce being a Ligurian invention) and bottles of limoncino (the local variation on limoncello, the lemon-based liqueur commonly associated with the Amalfi Coast, in Italy’s south).

Entering Vernazza from the train station, a massive wall poster illustrates how, on October 25, 2011, the village suffered flooding and landslides that buried it under four metres of mud and turned the main street of Via Roma into a raging river, resulting in more than €100 million worth of damage and the deaths of three locals. The toll would likely have been higher if the disaster had occurred in summer.

IN THE HIGH SEASON, from June to August, the Cinque Terre can be crowded. Though the entire region has fewer than 5,000 residents, it draws upwards of 2.5 million visitors a year. Local authorities are exploring ways (entrance tickets; turnstiles at village gates?) to reduce numbers (they have been threatening this for years). Until then, dodge the mob by dropping by in spring or autumn.

Vernazza is ideal for an al fresco bite. (A trivial aside: though “al fresco” equates with “outside” in respect to dining, it literally means “in the chill” in Italian, which is slang for “in jail”.) Local specialities include trofie pasta, traditionally made from chestnut or wheat flour, and torte di verdure, which are vegetable pies stuffed with artichoke, potato, leek, zucchini and parmesan.

A popular dish is cotolette di acciuga, or anchovies stuffed with a breadcrumb-based filling and then fried. Gulf of La Spezia mussels are also nationally renowned

Seafood is on every Cinque Terre menu, the area’s anchovies being celebrated throughout Italy. A popular dish is cotolette di acciuga, or anchovies stuffed with a breadcrumb-based filling and then fried. Gulf of La Spezia mussels are also nationally renowned.

Those crowds can make lunchtime tables hard to come by, however. For a meal on the move, you’ll notice many visitors stabbing long wooden skewers into cono di fritto misto, which are big paper cones crammed with fried calamari, prawns, anchovies and chunks of white fish.

AND FINALLY, NO trip to the Cinque Terre would be complete without taking to water. Complementing the Cinque Terre Express, shiny ferries ply the coast for much of the year. The dash from Vernazza to MONTEROSSO AL MARE, the largest and most northerly of the villages, takes 10 minutes.

With its French Riviera-esque atmosphere, Monterosso is also the least quaint of the five (with a seaside car park), its boardwalk lined with swanky hotels and restaurants, and lively bars and pizza joints. But it also has a long, sandy beach — its daytime USP. In that oh-so-Italian way, the beach is privately run and regimented, and you will need to shell out about €20 for a brolly and two sun-loungers.

And when the sun finally retires for the day, most visitors head for one of Monterosso’s seafront hangouts for an aperitivo and people watching.

As appears to be their wont, the white-clad, selfie-chasing duo have nabbed a prime spot, there to share an antipasti ai frutti di mare — a platter of mixed “fruits of the sea” — accompanied by glasses of the local plonk, which is a dry white coaxed from the bosco, albarola and vermentino grapes of the surrounding hills.

With the lights of anchovy boats freckling the horizon, and with their photos likely uploaded and busy influencing, the couple have put their phones away. Now they gaze only at each other, like a pair of moony swans. ◉

This travel story ran in Post Magazine in 2019. Download PDF.

SHARE