Hong Kong has long been defined by its 'can do' attitude, and the collective determination of its people to better their lives — sometimes against seemingly insurmountable odds.

MANY SOCIETIES FLATTER themselves with tales of a core value supposedly in their DNA. The British have their so-called “Blitz Spirit”, a teeth-gritted resolve said to have been shared by the people during the Germany’s intensive bombing campaign of World War II. Americans, meanwhile, are always keen for personal improvement, as promised by the “American Dream”.

On the other side of the planet, many of Hong Kong’s 7.4 million people also take pride in an intangible quality that they claim as their own. The “Lion Rock Spirit” — which describes their collective determination to better their lives against seemingly insurmountable odds — is, believers say, hardwired in the Asian city.

After all, many older Hong Kongers — or their parents, at least — arrived in the tiny territory on China’s southern periphery as refugees with nothing, fleeing from turmoil in mainland China between the 1930s and ’60s, when Hong Kong was still a British colony. It was their resilience and hard work, they insist, that transformed their city into a global financial centre in just one generation.

“We all had to work hard back then,” says an 80-something gent (“call me Chan”) smoking a Double Happiness cigarette under a no-smoking sign, as he watches an impromptu basketball game in the concreted play area and the light fades over his sprawling public housing estate .“If you did not you would go hungry, your children would be hungry. Everyone was working hard for their future.”

‘THE LION ROCK SPIRIT was a common belief in my parent’s generation,” says Bryony Hardy-Wong, 43, whose mother and father arrived from mainland China in the 1960s, and who was brought up on a similar housing estate. “Most of them were from humble background. What they believed was to work hard, and then they could win the opportunities to climb up the social ladder.”

Hardy-Wong, who works as a communications manager in the city, cites the case of local tycoon Li Ka-shing, who arrived with his family in the ’40s, fleeing war and living in extremely humble circumstances in their exile. The death of Li’s father from tuberculosis meant he was forced to leave school at 15, working 16 hours a day in a plastics trading company.

Now retired and in his 90s, Li is believed to be the wealthiest person in Hong Kong — a go-getting metropolis with a GDP per capita on par with that of Germany. Li’s assets, according to Forbes magazine, top US$35 billion. “Li Ka-shing is always a role model for the older generation,” Hardy-Wong says.

A SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION of China since 1997, hilly Hong Kong comprises three distinct areas: Hong Kong island; the Kowloon peninsula, just across the busy waters of Victoria Harbour; and the largely rural New Territories that mainly stretch between Kowloon and China proper.

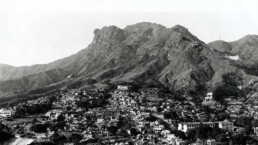

Kowloon means “nine dragons” in Cantonese, denoting a 13th-century Chinese emperor and a procession of eight hills cutting between the peninsula and the New Territories. Lion Rock is one of those hills, its 495-metre peak topped by a huge and distinctive granite outcrop that in silhouette from Kowloon really does resemble a crouching lion.

The lives of refugees from mainland China in Hong Kong had always been tough, but between 1945 and 1951 — firstly with China’s civil war raging and eventually with the 1949 victory of Mao Zedong’s Red Army and its revolutionary aftermath — the city’s population more than tripled, from about 600,000 to more than 2 million.

The influx of so many desperate people into the British colony resulted in a severe housing shortage, with hundreds of thousands squeezing into ramshackle squatter communities on Kowloon hillsides. There they struggled to survive in squalid conditions, suffering from hunger and malnutrition, poor sanitation and disease outbreaks, as well as extreme competition for work, low pay and exploitation by bosses.

The squatter huts were largely made of discarded wood and other waste materials, and residents cooked on open fires. Accidental conflagrations, then, were another threat, but the colonial administration largely turned a blind eye, perhaps believing the refugees would return to China sooner or later. Then, on Christmas Day, 1953, a fire raged through Kowloon’s Shek Kip Mei squatter area, making 53,000 people homeless overnight.

By 1972, an ambitious public housing programme promised that affordable homes would be created for 1.8 million citizens, or about 45 per cent of the entire population at that time

To its credit, the previously languorous administration acted swiftly, distributing food and other necessities, and constructing shelter homes. A plan was made to clear the squatter areas and a fund was established for the construction of resettlement buildings — forerunners of the subsidised public housing estates that for decades made the Hong Kong government the world’s biggest landlord.

By 1972, an ambitious public housing programme promised that affordable homes would be created for 1.8 million citizens, or about 45 per cent of the entire population at that time. This would be achieved through the building of new towns in the New Territories and many high-rise estates in Kowloon, including those in Wong Tai Sin, Tsz Wan Shan and Wang Tau Hom that sit directly beneath Lion Rock.

STARTING IN 1974, the hardscrabble lives of the underprivileged of this part of Kowloon were dramatised in an emotive TV series called Below the Lion Rock, which ran over five series on government-run channel RTHK.

The series tackled the hard socio-political realities of the changing times — everything from rampant corruption, drugs and gambling addiction to the struggles of ex-cons and the disabled — with true-to-life characters ranging from a street hawker and a civil servant to a reporter and a fireman. The button-pushing drama resonated with the downtrodden and the working class.

According to Helena Wu, assistant professor of Hong Kong studies at Canada’s University of British Columbia, writing in her 2020 book The Hangover after the Handover: Places, Things and Cultural Icons in Hong Kong, “it was reported in 1974 that only 1% of the local population had never watched the show”.

The programme became even more popular in 1979, boosted by a sentimental new theme song — also called Below the Lion Rock — performed by much-loved Canto-pop crooner Roman Tam. The roughly translated lyrics, in part, read: Of one mind in pursuit of our dream / All discord set aside / With one heart on the same bright quest / Fearless and valiant inside / Hand in hand to the ends of the earth / Rough terrain no respite / Side by side we overcome ills / As the Hong Kong story we write.

[Financial secretary Anthony Leung] used the song to evoke nostalgic reminiscences of Hong Kong’s economic success created by an uncomplaining, perseverant and diligent people who supported each other”

Dr Maggie Leung, University of Hong Kong

However, while the 1970s ditty might now be considered the unofficial anthem of the city, for most people the Lion Rock Spirit is a 21st-century phenomenon.

“The song became part of the collective consciousness of the mass from 2002, when the then financial secretary Anthony Leung cited the song’s lyrics in his budget address,” explains Dr Maggie Leung, a lecturer in Hong Kong studies at the University of Hong Kong.

With the city’s economy badly battered by the financial crisis and the Sars epidemic at the time, and in an appeal to citizens to support his budget, the academic says the financial secretary “used the song to evoke nostalgic reminiscences of Hong Kong’s economic success created by an uncomplaining, perseverant and diligent people who supported each other”.

Since then, other politicians have used the track whenever they have felt a need to raise morale in Hong Kong. Also in 2002, Zhu Rongji, then the premier of China, included Below the Lion Rock lyrics in a speech promising economic support for Hong Kong. In 2013, with political discontent increasingly bubbling locally, the government incorporated the tune into a “Hong Kong Our Home” community cohesion campaign.

However, while these exhortations may have appealed to more senior citizens (perhaps remembering the bad old days with a time-twisted wistfulness), many in the younger generation have since deployed the Lion Rock Spirit to ends that are directly opposed to those of the established order.

This was most dramatically demonstrated when political activists climbed the rock to make a bold demand for universal suffrage during the pro-democracy “Umbrella Movement” protests of 2014, and when thousands of their torch-carrying comrades enacted a brilliant gesture from its summit during the more confrontational anti-government demonstrations that engulfed the city in 2019.

‘THE HANGING OF A gigantic banner during the Umbrella Movement in 2014 … as well as the forming of the glistening human chain to the top in the 2019 protest, are evidence of the symbolic significance of Lion Rock,” says Maggie Leung.

“We think the spirit of Lion Rock isn’t just about money,” one of the anonymous youngsters behind the banner said in video footage the group shared of the 2014 stunt, adding: “This kind of fighting against injustice, strength in the face of troubles, is the true Lion Rock Spirit.”

Hong Kong was economically transformed between the 1950s and the ’80s, and there can be no doubt that the industry of a determined working class played a significant role. But experts agree that there were multiple reasons for the city’s rapid development — everything from free education in the British colony and the rule of law to a large workforce in a compact location with rapidly improving infrastructure, as well as the many advantages of being the gateway to a mainland China that was about to open up to the world and institute economic reforms.

And today, while the life priorities of the working class will be much the same as for their parents and grandparents in tough times, few young adults will have watched any of the 15-minute, black-and-white early episodes of Below the Lion Rock. What’s more, the dramatic growth of Hong Kong’s middle class in recent decades means the Lion Rock Spirit has mutated to become something new.

With many of today’s young adults having been through higher education, and with the financial support of their parents, “the 1970s concept of Lion Rock Spirit is no longer applicable” in Hong Kong and “the socio-economic situation has changed”, says Hardy-Wong, while one core concept has stayed the same.

In essence, the lyrics of the Below the Lion Rock theme say that while there will always be struggles in life, the people of Hong Kong can make their lives better by pushing their differences aside and being supportive of each other. Everyone is, after all, in the same boat, and that solidarity still holds for many.

“The conventional good professions such as doctor and lawyer are no longer the careers [the younger generation] pursue,” says Hardy-Wong. “Therefore, the Lion Rock Spirit is used more for social context now, especially after the social movement in 2019, when the people shared the same values, eager to voice their opinions and demands, to strive for a just and equal society.” ◉

This story ran on the BBC Travel website in May 2022.

SHARE