With the Afghan capital beginning to show signs that decades of war and suffering may at last be over, a book from the 1970s recalls the magical oasis city it once was — and might be again.

Note to reader: This story dates from 2005. Now, some 16 years later, with the withdrawal of US and Nato troops from Afghanistan and the Taliban back in power, any kind of Kabul renaissance appears unlikely, to say the least.

IN A NATION WHERE about 80 per cent of the people are illiterate, Shah Muhammad Rais understands the power of words. Wedged into the floor-to-ceiling shelves of his Shah M Book Co’s little and curious shop in central Kabul, there are enough volumes on Afghanistan’s intriguing capital, on its romanticised culture of proud warrior tribes and recent decades of conflict and strife, to fill a library.

There are treatises on the fundamentalist Taliban that subjugated this war-torn Islamic nation before being ousted by the US military just three years ago. There are tomes on the poetic Dari language, on swashbuckling kings, on intricate ceramics and exquisite carpets. And there are scores of bandwagon-jumping books rush-released in recent years — Afghanistan: Unveiled rubs up against Afghanistan: Lifting the Veil, which chafes against Unveiled: Voices of the Women of Afghanistan.

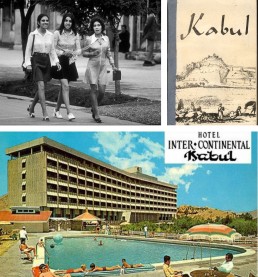

One book worth searching out is An Historical Guide to Kabul, first published in the early 1970s, when high-grade but extremely cheap hashish made the oasis city an unmissable stopover on the hippy trail.

Nancy Hatch Dupree’s sparkling account of the Afghanistan capital tells of music and dancing and rooftop supper clubs. Of bars, pizza parlours and Ariana Afghan Airlines flights from London, Paris and Rome to “a fast-growing city where tall modern buildings nuzzle against bustling bazaars, of wide avenues filled with colourful, flowing turbans, gaily striped chapans, mini-skirted schoolgirls, a multitude of handsome faces and streams of whizzing traffic”.

And it makes you want to cry for missing the party.

TODAY, IN 2005, the traffic has certainly returned. It rarely whizzes. Some avenues are wide, yes, but all are rutted, potholed and lined by open sewers.

Streets are usually gridlocked with farting, clapped-out Toyota Corollas (no longer wanted in neighbouring Pakistan and Iran), the occasional donkey-drawn cart overloaded with crates of Pepsi, and the shimmering new Toyota Landcruisers favoured by personnel at the more than 2,000 aid groups now operating in the country. Locals snigger as the chunky, gas-guzzling, tinted-windowed vehicles pass by, calling them “bullet magnets”.

Bruise-eyed street urchins flit between the cars to sell the Kabul Weekly newspaper for a dollar. Cover price of the tri-lingual tabloid (Dari, Pashto, English) is just five Afghanis, or about 10 cents. Most of the kids are orphans.

The battered national carrier Ariana — jokingly referred to as ‘Inshallah Airlines’ — currently flies as far as Frankfurt thanks to donations of reconditioned planes from India and other supportive nations

Like many Afghans, the children are, as Hatch Dupree wrote more than 30 years ago, also striking in appearance. It is believed that the troops of Alexander the Great of Macedonia, who conquered the region in the 4th century BC, added to the local gene pool of Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Hazaras, Turkmens, Nuristanis and other tribes. It is common to meet Afghans with pale eyes, aquiline noses and fair skins.

The battered national carrier Ariana — jokingly referred to as “Inshallah Airlines” — currently flies as far as Frankfurt thanks to donations of reconditioned planes from India and other supportive nations. But though laminated pictures of scantily clad Bollywood babes decorate shop windows, there are no mini-skirts turning heads on Kabul’s streets.

Women still cover up under black chadors and headscarves in public, and far more blue-shrouded, ghost-like figures glide through the city in head-to-toe burkas than the “unveiled” literary set would care to admit. Even female beggars plying Chicken Street — original hangout of 1970s hippy travellers — don eye-hiding burkas. Their bird-like calls for “baksheesh” strain through the billowing garments’ dehumanising facial grills.

CHICKEN STREET HAS regained some of its freewheeling charm, however, to once again be lined with ramshackle shops selling lapis lazuli chess sets, muskets and daggers inlaid with mother of pearl, rough-hewn glassware from Herat and musty sheepskin coats of the likes last seen on Jimmy Hendrix and Janis Joplin.

Flat, woollen pakol hats — as worn by the “Lion of Panjshir”, a guerrilla fighter who led Northern Alliance against the Taliban — are big sellers at $10 for four. The hats are labelled “In the Memory of Afghans’ Proud Militant Ahmad Shah Massoud Shaheed”, who was the victim of two suicide bombers disguised as journalists just days before the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York. Massoud remains revered in Kabul, and portraits of the late general — looking part Che Guevara, part Bob Marley — hang from municipal buildings and rear-view mirrors all over town.

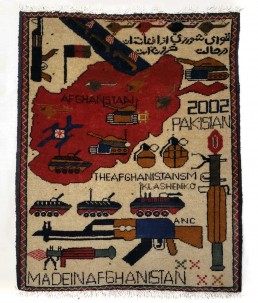

“Cities like Kabul change a little every day,” Dupree wrote back in the ’70s, when spaced-out visitors would spend days lazing in Chicken Street’s steamy teashops. Today, Kabul: The Bradt Mini Guide (co-authored by a former BBC journalist and the first guidebook to the capital in over 20 years) advises that visitors do not linger due to potential attacks in an area where $30 “war rugs” feature tanks, AK-47s, fighter jets and grenades, as well as words such as “WAR ON TERROR” and “ROUT OF TALEBAN”, woven into their patterns.

Dupree could never have imagined the extreme changes that Kabul would undergo with 23 years of conflict, starting when Soviet tanks rumbled into the Hindu Kush in 1979 and continuing through a blood-soaked civil war and the rule of the medieval, black-turbaned Talibs. Thirty years ago, enchanting Kabul was blessed with sparkling fountains, elegant civic squares and stately monuments that have since been reduced to rubble or, if lucky, are now pockmarked with bullet scars.

IN RAIS’S SHOP there are books on Greco-Buddhist relics from the days of Alexander that Afghans will never see again, snatched from the national museum and destroyed by the Taliban as idolatrous, or smuggled out of the country and flogged to private collectors overseas.

It is believed about 75 per cent of the museum’s exhibits were stolen or destroyed. As a depressing replacement of sorts, Kabul now has the Omar Mine Museum, which displays 51 of the 53 types of explosives recently deployed in Afghanistan, including the cluster bombs used to devastating effect by the US in its Operation Enduring Freedom.

The bookshop displays books on the cultivation of traditional Afghan gardens, once renowned for their fragrant rose beds and fertile apricot, pear and pomegranate orchards. Dupree’s guide describes the terraced Bagh-e-Babur Garden, named after the first Moghul emperor, Zahir-ed-Din Mohammad Babur Shah, who established a kingdom in Afghanistan in 1504.

In that garden in the ’70s, “magnificent stands of chinar trees shade reservoirs situated behind the mosque and above the tombs, and a profusion of sweet smelling wild rose, jasmine and other fragrant shrubs cover the mountain side”. During the civil war, opposing warlords controlled high ground surrounding the garden, and it frequently became a battleground.

Trees escaping destruction were chopped down by Kabulis and used for firewood in the frigid winters. In fact, massive deforestation and subsequent soil erosion across Kabul has resulted in a brume of airborne dust that cloaks the city in a semi-opaque haze.

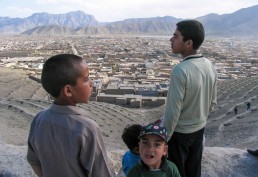

IF HISTORY HAS NOT been kind to Kabul, geography has been generous. The winding road up to ravaged King Nadir Shah’s Mausoleum — its catacombs the final resting place for 19th and 20th-century Afghan monarchs — is flanked by the rusting, skeletal remains of armoured cars and military transports, and paint-flaking DC-10s ripped in half by mortar shells.

But the view from the top is magnificent, revealing a sprawling, ochre-hued city ringed by mountains — craggy and lavender-tinged at Kabul’s perimeter, and imposing and snow-dusted to the distant west and north.

From this optimistic vantage point, atop a low hill called Tapa Maranjan in the centre of the city, a chaotic game of football can be seen taking place in the distant sports stadium where the Taliban stoned adulterers to death and amputated the hands of thieves. High above the dust and traffic, laughing children in spotless shalwar kameezes skip across wasteland once riddled with landmines. Hundreds of colourful kites dart and swoop in a clear blue sky.

Under the killjoy Talibs, kite flying — along with dancing, music, movies and TV — was illegal.

THOUGH THE PACE of Kabul’s revitalisation is dawdling, it is underway. The city’s golf course, established in 1967 and once popular with diplomats, has reopened. Caddies double as bodyguards. The Hyatt hotel chain has broken ground on a five-star property set to open in 2007. The Aga Khan Foundation has committed to restoring Bagh-e-Babur Garden and other historical monuments to their former glory.

And while our newspapers bombard with terrifying reports of bombings and rampaging mobs, hospitality to outsiders comes as naturally to the average Kabuli as drinking sweet tea and breathing dusty air. In short, in this city of fierce contradictions and massive change, we should not believe everything we read. And book-loving Rais would agree.

Although he has been given the pseudonym Sultan Khan, Rais is the unwitting subject of international bestseller The Bookseller of Kabul, and he is furious at what he has called Norwegian author Asne Seierstad’s “lies and distortions”. Rais aggressively claims her “low and salacious” book defames and completely misunderstands his brutalised but defiantly unbowed country and its complex and tradition-bound culture.

The Bookseller of Kabul is, ironically, perhaps the only book about Afghanistan that will never grace the Shah M Book Co’s busy shelves. ◉

This travel story ran in Vancouver’s The Georgia Straight magazine in December 2005.

SHARE