Once a welcoming oasis where East met West on the Silk Road, China’s exotic desert city of Kashgar still thrives on trade and ancient traditions. Stand in its way at your peril.

“BOISH! BOISH! BOISH!” Hear that yelled refrain in Kashgar and unless you’re okay with being trampled by belligerent bullocks, steely-eyed goats or even a Bactrian camel or two, you had better take notice.

When local herders, cattle drivers and market traders bellow “Boish! Boish! Boish!” they really do mean it. They are “Coming Through!”

Kashgar is the western-most city in China, sitting immediately east of the snow-capped Pamir mountains and the Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan borders, and on the edge of the forbidding Taklamakan desert. It was once a welcoming oasis where Silk Road traders would rest on overland odysseys between China, India, the Middle East and the Mediterranean.

Memories of the last jingle-jangling camel caravans to kick back in Kashgar have, of course, long been lost to the sands of time. Today, an immense statue of Mao Zedong looms over People’s Square in Kashgar’s modernised centre, and the city has largely succumbed to concrete, losing much of its romantic allure.

But adventurous travellers will discover that dusty pockets of mud-brick dwellings, handed-down callings and ancient ways remain. One is Kashgar’s riotous livestock market, which takes place every Sunday and transports the visitor back in time.

EVEN BEFORE SUNRISE, dirt tracks north of town are busy with farmers, shepherds and cattle dealers travelling on foot, on motor-trikes, ass-drawn carts and any makeshift conveyance that might get animals to market. Fine desert dust kicked up by the braying, neighing livestock fills the dry air with a choking smoke, and parched voices rasp through the haze. “Boish! Boish! Boish!”

By 10am, the entire area is transformed into a vast open-air beast bazaar. Prices are argued over, deals are made and hands are slapped together noisily, shaken theatrically

Trading begins even before market is reached. Sheep are shorn in the shade of poplar trees that have been planted tightly along all roads to fend off the encroaching Taklamakan. A tall and flinty old gent checks a stallion’s teeth beside an irrigation ditch while robust men haul stubborn cattle from the platforms of pick-up trucks. Potential buyers test-ride unruly horses, whipping at their hides with olive branches.

By 10am, the entire area is transformed into a vast open-air beast bazaar. Prices are argued over, deals are made and hands are slapped together noisily, shaken theatrically. Brick-like wads of red banknotes are pulled from pockets. And always that frenzied cry. “Boish! Boish! Boish!”

WITH AN OFFICIAL population of just 350,000, Kashgar is the urban home of China’s Turkic-descended Uighur minority people, whose language and customs owe more to nearby Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and even Afghanistan than most of the People’s Republic.

The Muslim Uighur men have a penchant for facial hair, the women wear scarves or veils in public, and all have a taste for aromatic mutton kebabs and chewy flat bread, which are up for grabs in every restaurant and on every street corner. Many shop signs are decorated with Arabic script.

Kashgar has embraced the push and shove of international trade for millennia, in fact. When Marco Polo passed through in the 13th century he noted, “The inhabitants live by trade and industry … [Kashgar] is the starting point from which many merchants set out to market their wares all over the world.”

And with Polo’s observation in mind, we have employed the services of Ablimit Ghopor, an affable Uighur gent who goes by the English handle Elvis (“I wanted a name that would make me sound more famous than something like John,” he says). His choice of moniker seems to have done the trick — Elvis is the king of Kashgar’s professional guides. He is also a Uighur-music aficionado, the go-to guy for Xinjiang carpets and an all-round expert on his city.

ELVIS LEADS THE way on a whistle-stop tour of the labyrinthine quarter immediately south of Kashgar’s lemon-hued Id Kah Mosque, arguably the largest Muslim place of worship in all China, accommodating up to 8,000 worshippers at a time. Uighur handicrafts flourish in this compact district, including the fashioning by hand of rugs and tapestries, of embroidered hats and distinctive pocket knives adorned with coloured-glass beads.

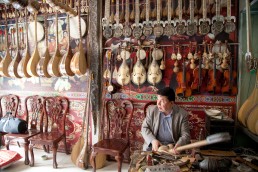

Perhaps Polo experienced the hubbub on Kumudai’erwazha Road, a single street in the old part of town where the wheels of cottage industry spin rapidly. In the Aysahan Musical Instrument Factory, a family business that’s been operating for six generations, proprietor Ablimit Aysahan Hajim is putting finishing touches to a long-necked, five-string tambour (a mandolin-like instrument with a long narrow neck and a bulbous half-pear-shaped body). His teenage son strums a smaller seven-string rawap adorned with grey snakeskin.

The driver, who sits atop, not inside, his jalopy, is bellowing at the top of his lungs. ‘Boish! Boish! Boish!’ Everyone grabs their stuff and darts for doorways and alleyways

Just across the way, four generations of another Uighur family squat on the pavement outside their workshop. They hammer and polish peculiar copper pots used in the preparation of delicious Uighur ice cream. “You put the pot in half of a wooden barrel filled with ice,” Elvis explains. “The milk goes inside the pot, maybe with some nuts, dried apricot pieces and honey, and then you just keep stirring.”

Suddenly a three-wheeled vehicle approaches at speed. An automotive Frankenstein’s monster seemingly stitched together from assorted spare parts and hope, the contraption is piled high with kettles, woks and more pots. It belches diesel funk.

The driver, who sits atop, not inside, his jalopy, is bellowing at the top of his lungs. “Boish! Boish! Boish!” Everyone grabs their stuff and darts for doorways and alleyways.

KASHGAR ALSO HAS a substantial Han Chinese population, of course, and that group’s tastes and traditions are part and parcel of the modern-day Kashgar experience. Jade from desert cities such as Hotan, southeast of Kashgar, has historically been abundant in the region. Hotan’s white “mutton-fat” jade is the most precious in China, in fact.

Elvis, through boyish charm and gentle determination, manages to gain us access to a couple of backstreet jade workshops where more affordable pieces are being crafted. In one cramped, windowless and dimly lit room, its walls coated with a film of jade dust so fine that it clings to the clothes like icing sugar, six young Han artisans are hunched over benches.

One of them is helpful twenty-something Lanny, from Fujian province on the opposite side of the country, who carves intricate animal motifs onto a thumb-sized chunk of pale-green stone. The piece will take her two days to complete, she says cheerfully, and will sell on the street for perhaps Rmb2,000 (then about US$320).

And as the light begins to fail, and with our mini-tour complete, we finish up in the steamy and seen-better-days Ostangboyi Teahouse, joining a languid gathering of elderly Uighur gents sipping rose tea on the balcony. It is a scene surely unchanged in centuries.

In the street below, nimble pedlars, balancing baskets of braided deep-fried dough on their heads, weave expertly through the jostling crowds. Another hectic day of trade and industry is coming to a close in Kashgar, and a now-familiar cry rings out all around as Elvis refills our teacups. “Boish! Boish! Boish!” ◉

This ran in Post Magazine in 2012 (see PDF), when redevelopment of Kashgar's old town was already underway but far from complete, and before the Chinese Communist Party under Xi Jinping decided to incarcerate huge numbers of Uighurs in 're-education' camps.

SHARE