A veteran civil rights activist says GIs were on the frontline of the anti-Vietnam-war movement, organising protests, publishing underground newspapers and serving jail time to end the fighting in Southeast Asia.

THE STEREOTYPICAL IMAGE of the Vietnam war veteran, returning to the United States after an arduous tour of duty, only to be spat upon and cursed as a murderer by sneering, long-haired peace protestors, is seared into the American psyche like a scar from a white-hot burst of napalm. The accepted belief is that weary veterans trudged home to be condemned, cold-shouldered, even physically assaulted — simply for doing their duty.

In popular culture, the phenomenon was memorably depicted in 1982 movie First Blood, which unleashed Sylvester Stallone’s traumatised John Rambo on the world. “I did what I had to do to win, but somebody wouldn’t let us win,” the grudge-holding former Green Beret howls at the film’s climax. “Then I come back to the world and I see all those maggots at the airport. Protesting me. Spitting. Calling me baby killer …”

Veteran American activist Ron Carver insists that GIs returning from Southeast Asia to be spat upon at home is a “myth”, arguing that soldiers — even soldiers on active duty — were at the heart of the 1960s and ’70s peace movement in the US. Returning servicemen and women were so appalled, he says, by what they had seen some 14,000 kilometres away from Washington DC — by what they had done, in some cases — that they became the most motivated and powerful voices against the war.

“Anti-war GIs led every major peace march in America from 1968 on,” claims 71-year-old Carver, an associate fellow at Washington-based progressive think tank Institute for Policy Studies. “They were leaders of the anti-war movement. The movement was not in conflict with the soldiers. The anti-war cry was supportive of the soldiers. It was, ‘Bring the troops home’. It was, ‘Bring them home alive.’”

IT’S A BLUE-SKY Saturday morning in March in Ho Chi Minh City, capital of South Vietnam during the war and then called Saigon. Carver is guiding me through an exhibition at the War Remnants Museum. The facility remembers the drawn-out conflict that Vietnamese today call the Resistance War Against America and which, in one form or another, lasted from November 1, 1955, to the fall of Saigon to the communist North on April 30, 1975. The city was renamed in honour of the victor’s late revolutionary leader a year later.

Captured or discarded US tanks, Chinook helicopters, armoured personnel carriers and F-111 tactical bombers and other attack aircraft are parked at the museum’s entrance. The new exhibition, which took Carver more than a year to curate, is called Waging Peace and being held in a dedicated room adjacent to the bustling lobby.

Through 80 or so exhibits — photographs, case studies, official documents, letters, newspaper articles and underground newspapers produced by GIs — the exhibition salutes the American troops from the anti-war movement who, Carver says, were crucial to bringing the conflict to an end.

“I wanted to cover all the different types of resistance, so we include GIs who refused to deploy and went to jail, we have those who went to Vietnam but refused to go into combat, or went into combat and then stopped fighting. We have soldiers who led marches for peace in the US and elsewhere, and we have people who deserted and went into exile.”

The exhibition appears popular, attracting a curious brew of singlet-wearing backpackers, Vietnamese families and, one suspects, the occasional American vet footslogging over old stamping grounds. Just days earlier, in fact, more than a dozen veterans featured in Waging Peace flew in for the opening.

Among them was Susan Schnall, and a group has gathered around a dramatic photograph of her heading up an anti-war march in San Francisco in 1968 (opening picture), when she was a 25-year-old navy nurse. Schnall, originally from northern California and whose father was killed on a beachhead while serving in Guam in the Second World War, when she was just 14 months old, worked at Oak Knoll Naval Hospital in Oakland, California.

“I took care mostly of young men who came back from Vietnam wounded, and heard their terrible screams of pain during the night,” Schnall says by phone from her home in New York. “It wasn’t just their distress. I heard the terrible racist epithets they used towards the Vietnamese, the hatred they had, and I thought, ‘This war is 8,000 miles away, against people we don’t know, who have never been in the United States, never came here to harm anybody.’ I didn’t understand what we were doing so far away.”

Schnall was an organiser of the march, which she needed to promote and so printed 20,000 flyers. “I had a friend who was a pilot, so we took them up in a plane we rented and dropped them on military bases in the Bay Area,” says the 75-year-old, who wears her uniform in the photograph. “We also went to the Alameda Naval Air Station and dropped them on the USS Ranger.”

Schnall was arrested, charged with conduct unbecoming an officer and undermining the military. She was sentenced to six months hard labour.

WAGING PEACE OPENED on March 19, just three days after the 50th anniversary of the My Lai massacre, when a company of American soldiers killed hundreds of unarmed Vietnamese civilians — men beyond fighting age, women, children and infants — in the hamlet of My Lai in southern Vietnam’s Quảng Ngãi province. A number of women and girls were raped, including some not yet teenagers. Though army officers covered up the slaughter for more than a year, the truth was revealed in November 1969 to global outrage.

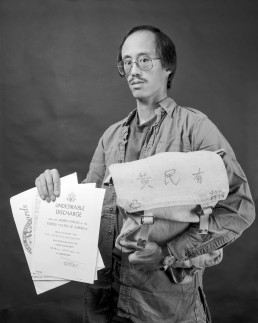

It was a brutal turning point for Mike Wong, whose portrait hangs in the Waging Peace exhibition. In the black-and-white photograph, the Chinese-American holds up the official notification of his “Undesirable Discharge from the Armed Forces of the United States of America”.

Wong, who also attended the exhibition opening in Vietnam, was born in San Francisco in 1947. His mother was also born in the city, to immigrants from China’s Guangdong province. His father was from Guangdong too, but died when Wong was a young child. He was brought up by his mother to see himself as a patriotic American.

“While in high school, I was in the JROTC, the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps in the United States, that is used to provide basic military training and indoctrination into the military mind-set and as a recruiting tool,” Wong, now 70, says from his home in San Francisco. “I was really gung ho. I believed everything that my government said — that the United States was always the good guy. I wanted to join the military right out of high school but my mother said, ‘No, you need to go to college,’ and being a good Chinese kid, I did what my parent told me to do.”

Wong was exposed to the growing counterculture while at college in San Francisco and in 1968, still a student, he received his draft notice, joining the army in January 1969. “I enlisted to get in the medics, so I wouldn’t have to kill anybody,” he says. “Then, once I was in the army, more and more soldiers were coming back, they might have been sergeants or instructors, and they were telling us about what was really going on over there. I heard stories about murdering civilians, about torture.”

Then came the nauseating gut punch of My Lai.

“Then, once I was in the army, more and more soldiers were coming back … and they were telling us about what was really going on over there. I heard stories about murdering civilians, about torture”

Deserter Mike Wong

“My Lai hit the front pages and had a profound effect on me,” Wong says. “Most of my unit then turned against the war. We almost had a riot at one point. Soldiers were saying, ‘They can’t make us do this — go to Vietnam and kill women and children.’”

In December 1969, Wong, while assigned to a hospital in Texas, received his orders for Vietnam. “I took two weeks leave, came home to San Francisco, got a lawyer and went Awol, a crime in the military,” he says. “Then I turned myself in to the Presidio stockade, an army jail at a base in San Francisco. I refused my orders for Vietnam. They had 15 years of charges hanging over me.”

Wong says there were so many soldiers trying to avoid Vietnam at that time that locking up everyone was not an option.

“So they released me from the stockade and put me back on Vietnam orders. I hid out for a while. While I was hiding out in San Francisco, I was going through a lot of mental turmoil, trying to decide what to do,” Wong says. “At one point, I decided I needed to stop thinking about this for a little while, so I went to Chinatown, to see a Chinese movie. I’m American-born, so I speak only a few words of Chinese, but you can tell what’s going on from the action. So I paid and went in. I didn’t even pay attention to what movie was showing.”

The film was about the Chinese struggle against the Japanese in the Second World War. “The Japanese were using the same tactics that we had been taught in the US military, and the Chinese were using guerrilla tactics like the North Vietnamese,” Wong says. “I realised that if I went to Vietnam, I would be doing to the Vietnamese exactly what the Japanese did to the Chinese in World War II.”

His decision was made. “I’m not going to Vietnam,” Wong told himself. “With the help of the underground railroad, I deserted to Canada.”

IT IS EARLY AFTERNOON when Carver and I quit the museum. The day’s temperature is peaking at 36 degrees Celsius, so we retire to the air-conditioned coffee shop across from the museum’s entrance. The cafe is next door to Carver’s two-star, US$25-a-night hotel, where the 20-something receptionist refers to him with a fond smile as “Mr Ron”. He orders a “to die for” pineapple smoothie.

In his loose-fitting, short-sleeved blue shirt, beige slacks and sensible shoes, with bald pate above his remaining white hair, Carver has the demeanour of a twinkle-eyed great uncle. A simple tattoo of a dove nests where thumb meets index finger on his right hand.

Carver’s career as an activist began in 1964, “the day I got out of high school in Boston”, when he headed south as a volunteer in the civil rights movement, working for the summer in the Atlanta headquarters of the Student Nonviolent Coordinated Committee.

Eighteen years old and just two weeks out of school, Carver was on duty when three civil rights workers, investigating the burning of a church in Mississippi, went missing on June 21, 1964. “I was given a list of all the jails and hospitals, state police and the FBI, and I called them all. I actually called the jail where [the three] were being held and the jailer’s wife told me they were not there, but later we found out that they were. Out of frustration, I called the FBI and they refused to do anything.”

The trio had been arrested for speeding, held in jail before being released and then followed. Their car was pulled over. They were abducted, driven to another location, shot at close range and buried. The case became known as the Mississippi Burning murders, and the direction of Carver’s life had been decided.

He attended his first anti-Vietnam war march in April 1965, in Washington DC. “By then, after my experience with the FBI, I’d become very sceptical about our government,” he says. “And when I began reading about the war and the two sides, pro and against, I was hesitant to believe them.”

After a year working in Mississippi, Carver went to Columbia University in New York to study American history. His time there further cemented his anti-authority beliefs. “In 1968, students at my university and others shut down and took over five buildings, including the main administration building,” he says. “We were arrested. I was severely beaten. I was 22.”

THE FACT THAT WE are discussing the anti-war movement in a coffee shop is apt because, Carver says, countless cups of Joe fuelled the GI resistance to Vietnam.

In the late 1960s, he explains, a network of coffee houses began to spring up near army bases in the US. “They became magnets for the anti-war soldiers. They could find each other and realise they were not alone. There they could plan protests, marches, demonstrations on base or off base.”

The first such cafe opened near Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, in January 1968. It was called UFO, Carver says, “as if it had dropped from outer space — it was so different from everything else culturally in Columbia”.

“There was an anti-war activist, a civilian from San Francisco, named Fred Gardner. He came up with the idea,” he continues. “He realised that most army bases are in remote areas and little army towns grow up next to them, but those towns are horrible, exploitative places.

“So when GIs get leave, what are their choices? Bars, jewellery stores with staff outside hawking, saying, ‘Hey GI, come buy something for your mother, buy something for your girlfriend,’ because they know people have just been paid. Or whorehouses. And he said, what if we open a San Francisco-style cabaret, he called it, a counter-culture location with rock and roll and posters on the walls.”

After graduation, Carver worked in such a coffee house close to Fort Dix in New Jersey, and later at another near Fort McClellan in Alabama. “We were all volunteers, no one got paid,” he says.

GI coffee houses soon proliferated across the country, drawing disaffected servicemen and also attracting interest — welcome and unwelcome — from elsewhere. Oleo Strut coffee house (named for a vertical shock absorber on a helicopter) was outside Fort Hood. When anti-war actress Jane Fonda visited to help out at Oleo Strut for a week — doing chores, listening to soldiers stories and speaking at a peace rally — a headline in a local newspaper, referencing Fonda’s role in a 1960s sci-fi flick, read: “Barbarella comes to Killeen, Texas.”

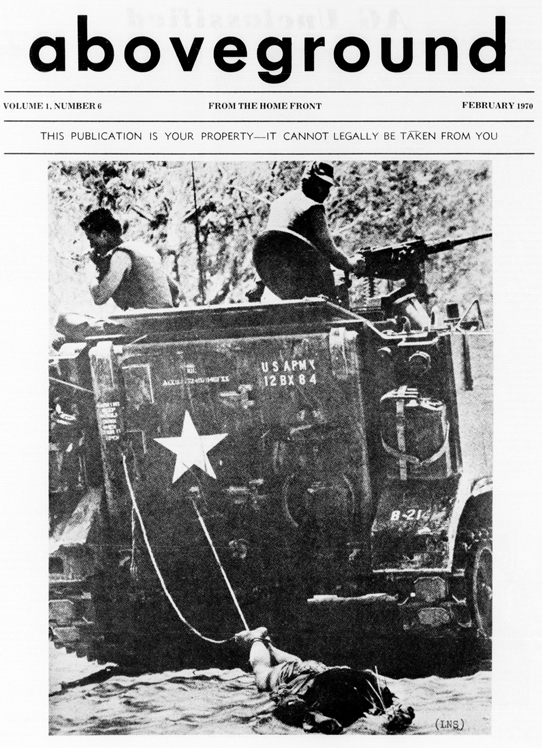

The coffee shops were also the unofficial newsrooms of underground newspapers produced by anti-war GIs, and they feature heavily in the Waging Peace exhibition. “They were the social media of their time,” enthuses Carver, adding that there were thousands of such DIY publications at the height of the war, packed with first-hand accounts from the frontline and damning information that military brass tried to suppress.

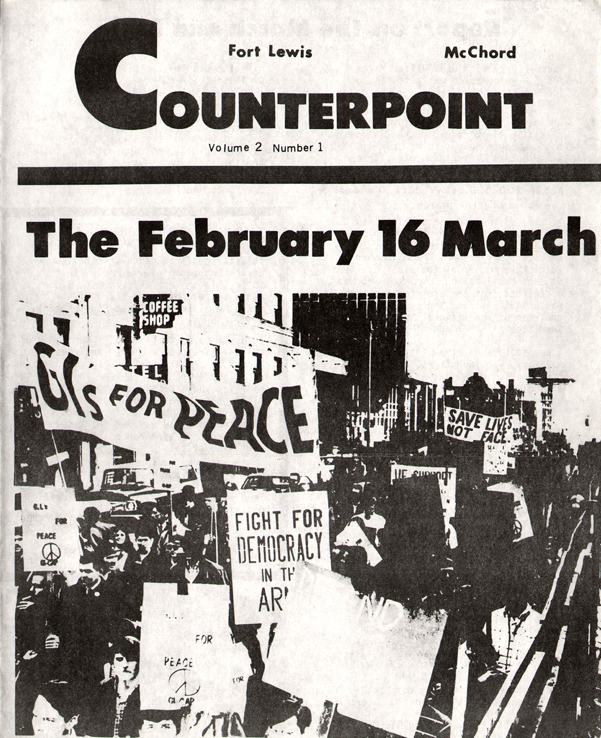

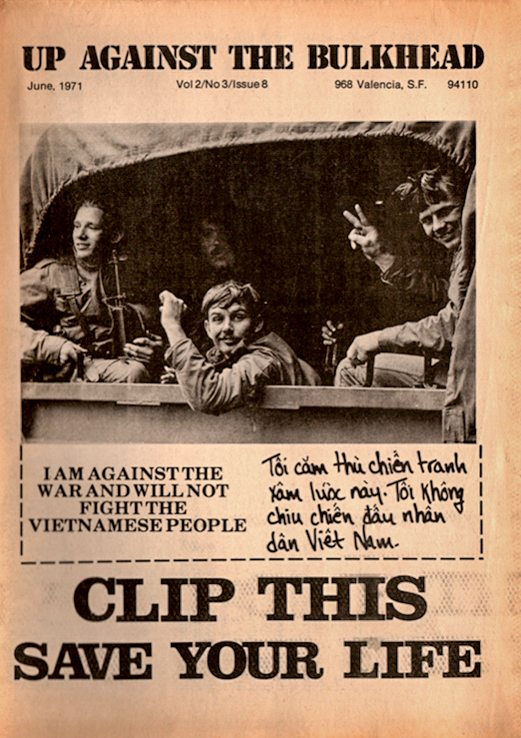

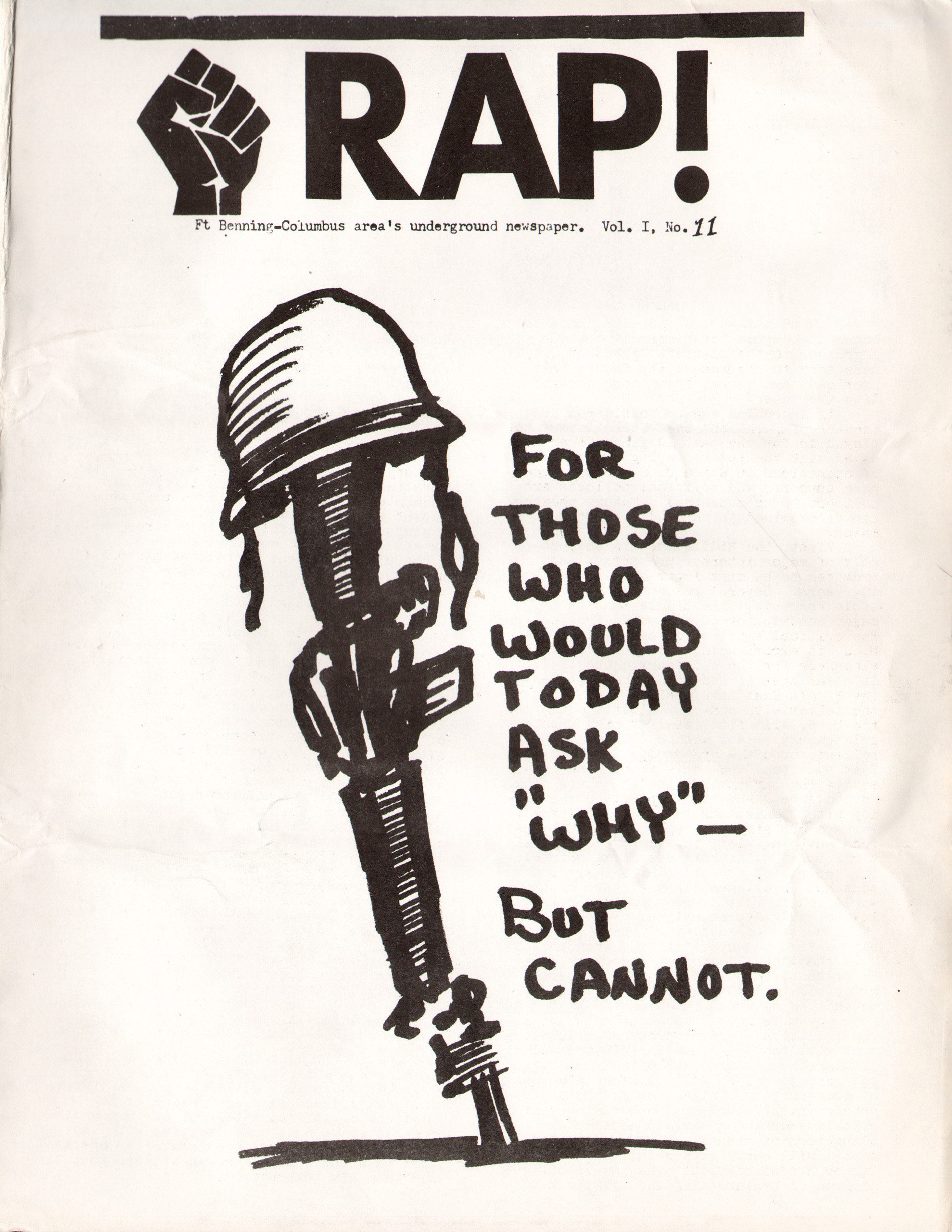

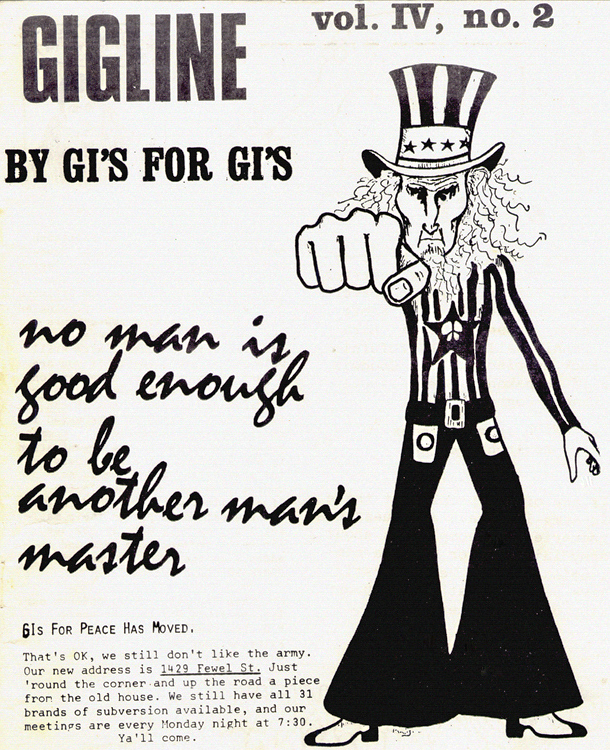

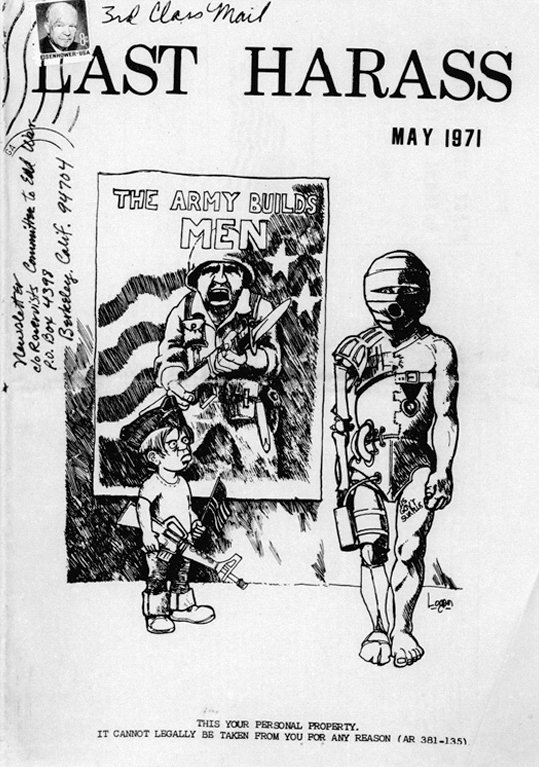

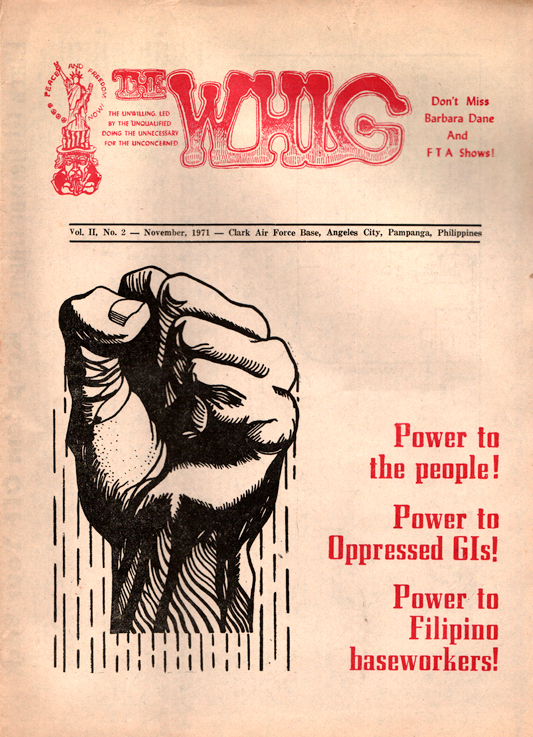

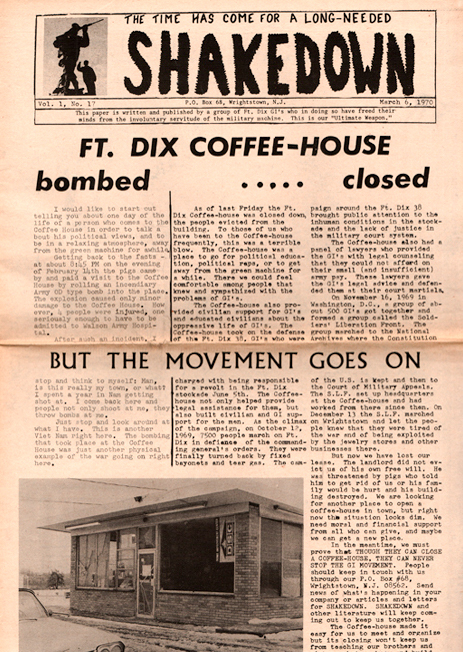

Titles included Aboveground (published at Fort Carson, Colorado), Gigline (“By GI’s for GI’s”; Fort Bliss, Texas), RAP! (Fort Benning, Georgia), Shakedown (Fort Dix) and Attitude Check (Camp Pendleton, California). Another portrait in the exhibition shows Skip Delano, who was assigned to Fort McClellan for training in the use of Agent Orange and other poisonous chemicals used in America’s herbicidal warfare programme. Delano published the newspaper Left Face while still on active duty.

Many such publications were free to GIs and carried on their front pages a statement that they were a soldier’s personal property and could not be confiscated. The phenomenon even spread overseas: The Whig was distributed at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines; ACT was for US deserters hiding out in France.

Underground newspapers proliferated on US military bases in the 1960s and '70s. Photos: Waging Peace

The military hit back against the coffee houses and the underground newspapers, using police to shut them down. Some were even bombed by vigilantes, including the coffee house where Carver worked at near Fort Dix. “The first time, somebody opened the door and threw in a concussion hand grenade,” he claims. “It did not do as much damage as a fragmentation grenade, but still injured one soldier.”

Others coffee houses burned to the ground, Carver says, adding that one near Camp Pendleton was shot into, wounding marine Jesse Woodward.

But Carver also admits that the GI resistance was not always peaceful, highlighting increasing instances of “fragging” in Vietnam as the war dragged on. The term describes the deliberate killing or attempted killing by a soldier of his or her superiors, usually using a fragmentation grenade. According to US army veteran and historian George Lepre, who has written extensively on the subject, the total number of known and suspected fragging cases by explosives in Vietnam from 1969 to 1972 was close to 900, with 99 deaths and many injuries.

“There were many recorded instance of soldiers killing their own officers,” says Carver. “If their lieutenant was too gung ho, asking them to do crazy things, at night they would throw a grenade into his tent and kill him …There’s nothing comparable in US military history.”

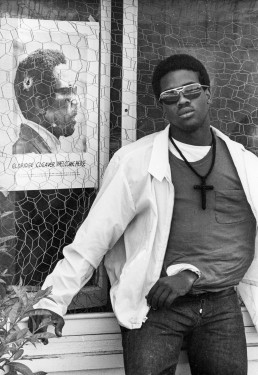

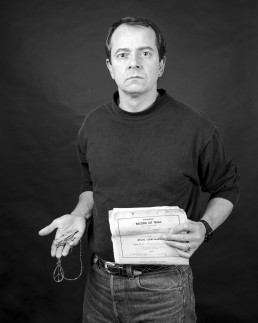

A NUMBER OF THE most anti-war GIs rebelled as a direct response to their own actions. One was William Short, a platoon sergeant in Vietnam who, alongside two colleagues, went on strike against the war, refusing to go on combat operations in April 1969.

“I was charged with leading a conspiracy, a mutiny against the US, later reduced to refusing a direct order, primarily because of pressure coming from the anti-war movement in the states,” Short, now 70, says from Los Angeles.

Ambivalent about the war from the beginning, “about the truthfulness of the government and whether the war was righteous”, Short was assigned to the first infantry division, operating out of Lai Ke about 60 kilometres northwest of Saigon. “Our job was to stop infiltration from the North coming down through the Ho Chi Minh Trail,” he says. “We would typically work out of small base camps in the middle of the jungle … and we would spend maybe three to five days patrolling the jungle on search and destroy missions, and ambush missions.”

Short says that it was a more senior-ranking sergeant, “somebody I looked up to for guidance”, who “got me started booby-trapping the bodies” of enemy killed in battle.

“I thought of the Second World War and Nazi soldiers involved in atrocities, the extermination camps, saying they were just following orders. I thought, I’ve gotta do something”

William Short, who in 1969 refused to go on combat operations

“We would pull the safety pin and put a grenade under the rib cage, just beneath the breast, so that it would hold pressure on the lever,” he says. “Then, when somebody would come along, maybe a friend of that soldier, and roll the body over to identify them, or in grief, the grenade would go off in his face.”

One night, having booby-trapped a body and moved on, Short heard a grenade go off.

“When you are in a platoon-size ambush, you are firing along with 20 other guys and you can wash yourself a little bit clean of what you are doing by saying, ‘I don’t know if my bullets actually killed that person, I’m just shooting with everybody else’ … But when that grenade went off that night, I started thinking, well, I have to face the fact that I really am doing what I’m doing. How can I justify it?

“I thought of the Second World War and Nazi soldiers involved in atrocities, the extermination camps, saying they were just following orders. I thought, I’ve gotta do something.”

AS MANY AS THREE million Americans served in uniform in Vietnam. While Carver does not claim anything like the majority were actively anti-war, and his claim that spitting on soldiers was a myth continues to be hotly debated, he insists that those who did fight back made a huge difference to public opinion.

Asked to name somebody he most admires from the movement, Carver appears reticent to answer, but he recalls Captain Howard Levy, a US army doctor who was court-martialled in 1967 for refusing to provide medical training to Special Forces heading for Vietnam. Levy, 30, a dermatologist, was convicted at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, for disobedience and seeking to promote disloyalty. He served 26 months in prison before becoming active in coffee house-organised protests in army towns across the US.

“He came to this conclusion three months before his [time in the military] was due to be over,” Carver says of Levy. “He never went to Vietnam. He wasn’t going to be sent to Vietnam. He could have played out those next three months and gone home, but as a matter of conscience, he couldn’t do it.”

“A lot of the early resistors,” Carver continues, “from 1965, ’66, ’67, before the movement grew larger, they had no idea that they were going to be inspiring other people to join, to take risks and stand for conscience,” Carver says. “They were much more alone.”

Over time, the peace movement grew to be so substantial that sentences were sometimes reduced or discarded in the face of popular opposition.

Schnall, who dropped the anti-war flyers from a plane over San Francisco, was not required to do her six months hard labour but to go back to duties. Now retired, she worked for 31 years in administration of public hospitals and is now active in supporting those suffering the poisonous legacy of Agent Orange. She is also president of the New York City chapter of Veterans for Peace.

Short was court-martialled twice for refusing to deploy, sentenced to two six-month prison sentences, busted from sergeant to private and imprisoned in Long Binh jail in South Vietnam. He was held for 64 days before being released.

On his return from Vietnam, Short joined the GI resistance movement, attended art school and today still runs his own photography business in Los Angeles. He took the portraits of Wong, Delano and others included in Waging Peace in the early 90s, while producing with his journalist wife a book called A Matter of Conscience, about anti-war troops and their individual experiences.

“By 1968, ’69, half were for the war and half were against, so it was clear to me that if I were to go to Vietnam and fight, half the country would say I was a hero, half would say I was a villain, a child killer”

Mike Wong

Wong remained in Canada for five years, completing a bachelor’s degree in social science at York University in Toronto. He returned to the US when the war ended. “They had a deal going that if you were an Awol soldier and turned yourself in at Fort Dix, New Jersey, and accepted a court martial and pleaded guilty to long-term Awol, they would give you an undesirable discharge and let it go at that,” he says.

He eventually took a master’s degree in social work and spent his working life in that field before retirement, the last 17 years providing care to elderly patients. Today he is active in highlighting the plight of and fighting for reparations for Asia’s comfort women during the Second World War.

Wong has no regrets about his decision to desert. “There was a strong feeling in the Chinese community that the Vietnam War was a rerun of China,” he says. “The Saigon government was corrupt and did not represent the majority of the people; [it was] the same kind of corruption that undermined the Chinese nationalists during their war.”

Wong also says that he, like many other soldiers, was forced into a no-win situation. “The country at the time was very divided,” he says. “By 1968, ’69, half were for the war and half were against, so it was clear to me that if I were to go to Vietnam and fight, half the country would say I was a hero, half would say I was a villain, a child killer.

“On the other hand, should I refuse to fight, either by going to jail or desertion or anything else, half would say I was a hero and half would say I was a coward. That was the struggle I went through, deciding where I stood with that. Finally I decided that having to choose between being called a murderer or a coward, I choose a coward.”

BACK IN HO CHI MINH City, Carver lists his reasons for creating the Waging Peace exhibition: “To honour the soldiers who led these revolts within the army,” he says. “To correct history; to inspire the younger generation that is now fighting for social justice, fighting for gun control, fighting against US militarism; to say that even though the odds look overwhelmingly in favour of this unmoored, right-wing government of ours, it’s worth fighting for what you believe in, and to organise.

“These guys organised within the army, carefully talking one on one, handed out their underground newspapers one to one, held discussions at the coffee houses, in the barracks, in Vietnam. There was an amazing level of organisation.

“I don’t want people to think this exhibition is just a nostalgic exercise, just one old crony honouring fellow old cronies. That’s not what it’s about.”

Just hours after Carver says those words, those 14,000km away in Washington DC, the student-led March for Our Lives will draw an estimated 800,0000 people onto the streets to demand greater gun control in the US.

With hundreds of supporting marches and other events held across the nation, total turnout will be estimated at between 1.2 million and two million people, making the action one of the largest protests ever held on American soil. ◉

The Waging Peace exhibition was held in Ho Chi Minh City in the spring of 2018, before moving to Notre Dame University in the US.