Psychic Surgeons of the Philippines

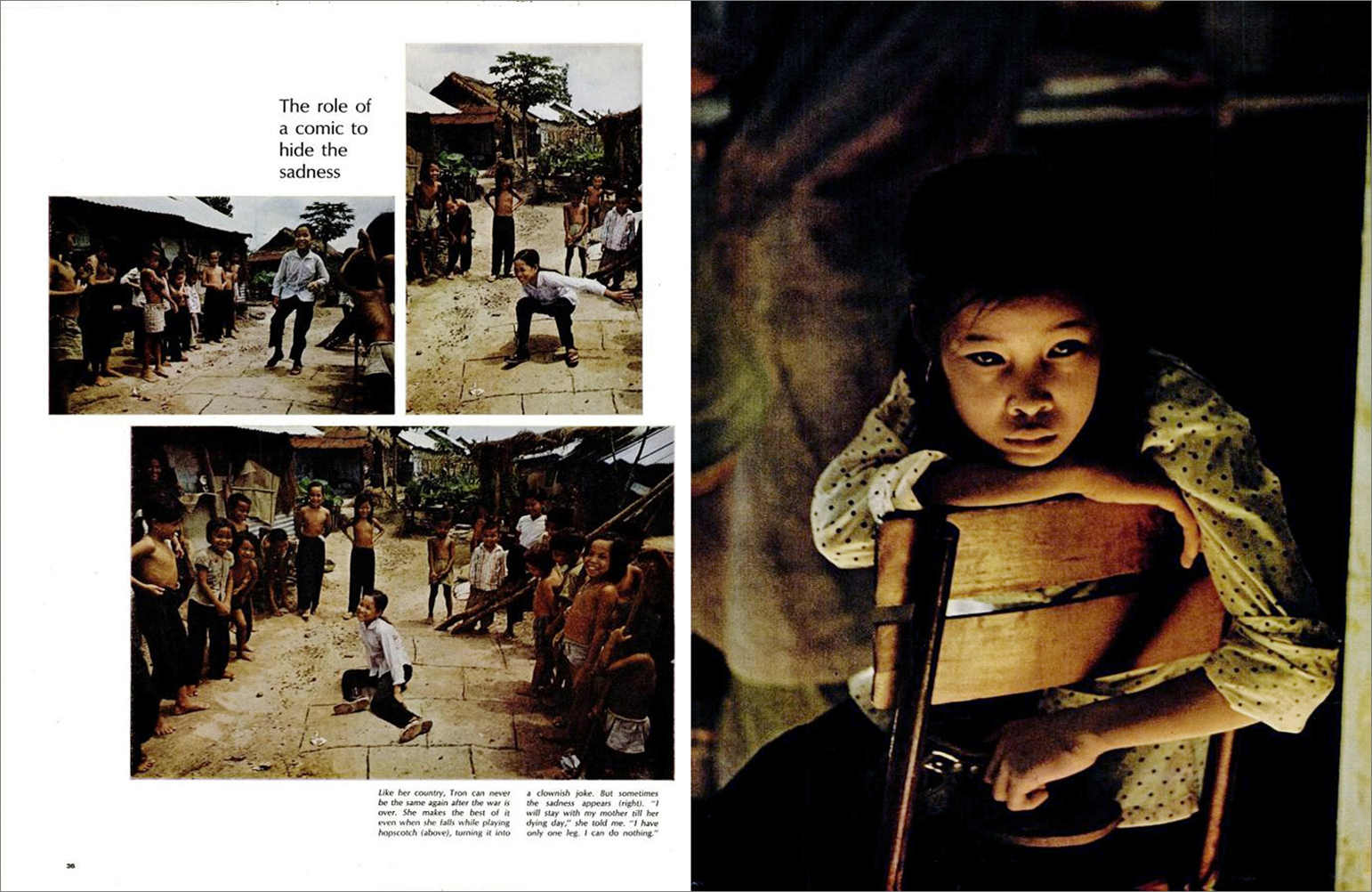

Cult American comedian Andy Kaufman spent his final days seeking a miracle cure for cancer on the operating table of a wealthy Filipino psychic surgeon, hoping that healing hands could succeed where Western medicine had failed. Fifteen years later, with a new Kaufman biopic starring Jim Carrey in cinemas, a question remains: are such faith healers for real, or are they just crooks?

“He was the Neil Armstrong of comedy. He went places no one else had gone”

— Jim Carrey on Andy Kaufman

SLEEVES ROLLED UP and eyes closed in prayer, psychic surgeon Jun Labo summons up the healing powers of the Holy Spirit, plunging both hands into his patient’s stomach. Blood spurts up his arms and across her chest.

Much kneading of grey flesh and the faith healer re-emerges triumphant, a dripping black mass of organic matter in his fist. The caption to the photograph reads, “Labo removes a large tumour from cancer patient with dexterity and care.”

The book Jun Labo — A Philippine Healing Phenomenon is not for the squeamish. Illustrating the work of the world’s most famous psychic surgeon, another caption reads, “Labo lifts eyeball out of its socket and inserts his left index finger under the eyeball to clean it.” And then there’s “a haemorrhoid being pulled out after psychic surgery”.

Readers will cringe as Labo makes “mucus, pus and phlegm ooze out of this Canadian patient’s throat”, squirm as “a worm appears from this patient’s stomach, possibly the victim of witchcraft”.

Believers claim Filipino psychic surgeons have a heaven-sent ability to perform miracles — to reach into the ailing human body without a scalpel or anaesthesia to cure everything from flatulence to cancer.

Sceptics, however, say it is a wicked scam, and that Labo and his paranormal pals have become rich by charging terminally ill American, European and Japanese patients up to US$200 a minute to perform a street-conjurer’s tricks, the tools of their trade being concealed packets of blood and offal from chickens, cows and pigs.

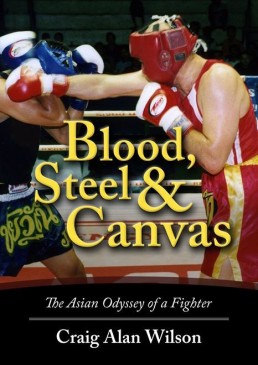

A BETTER READ IS Andy Kaufman Revealed! Best Friend Tells All, Bob Zmuda’s account of the bizarre life and untimely death of the cult American comedian who played bumbling mechanic Latka in the much-loved, early-1980s sitcom Taxi.

The book’s closing chapters describe how, in March 1984, a painfully thin Kaufman, suffering from advanced and inoperable lung cancer, had set out on a quest for a miracle. Given just three months to live by doctors in Los Angeles, he rejected Western medicine and made a 12,000-kilometre pilgrimage to Baguio, a ramshackle town high in the Philippines’ Cordillera mountains.

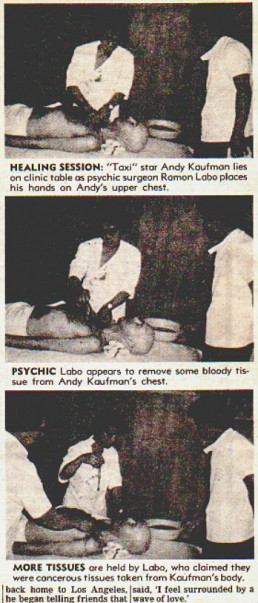

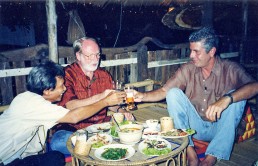

Believing Kaufman’s end was drawing near, Zmuda followed. In Baguio, he witnessed his friend — now sporting a Mohawk to disguise hair loss from chemotherapy — go under the psychic knife of a certain Jun Roxas twice a day for a month. Stripped to his underwear, Kaufman would wait with other patients for Roxas’s attention, shivering on an international production line of the sick and dying.

Once it was Kaufman’s turn, Roxas would appear to rip open the comic’s chest with his bare hands and remove great gobs of cancerous tissue. He then seemed to reseal the wounds with nothing but the power of prayer. Kaufman passed away on May 16, 1984, at the age of 35, less than a month after returning to the US.

Time and grief may have clouded Zmuda’s memory. Perhaps, as executive producer of one of the most anticipated Hollywood blockbusters of the year — the Kaufman biopic Man on the Moon, directed by Milos Forman (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest; Amadeus) and starring Jim Carrey — Zmuda has changed the surgeon’s name to avoid legal irritations.

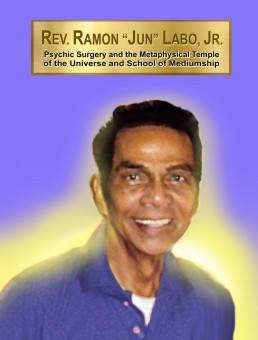

But, the fact is Roxas does not exist. Kaufman’s psychic surgeon was Ramon Labo Junior, better known as Jun Labo.

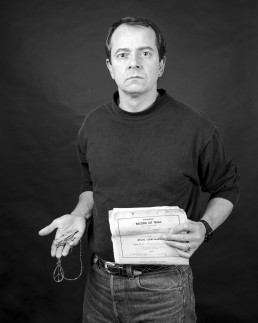

‘AH, YES, MR KAUFMAN,’ says Labo, squirming on an ornate white-wood and red-velvet throne. Surrounded by gaudy figurines of a bloody Christ and a weeping Madonna, the flamboyant faith healer is uncomfortable recalling a high-profile patient who died in the face of divine intervention.

“Mr Kaufman was very sick when he came to me. He was very skinny, very weak. The cancer had gone too far. I couldn’t help. He is with Jesus now.”

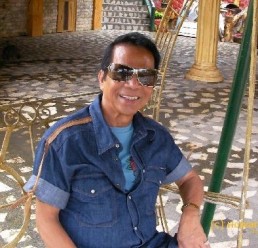

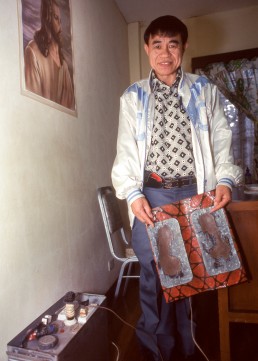

Labo is 65. He looks 45. He is short, lean, self-assured and tanned to peanut butter. His big hair is blow-dried. His small eyes are hidden by 1970s sunglasses. But the most striking thing about him is his jewellery.

On one wrist, a huge diamond and ruby-encrusted gold watch. On the other, a custom-made, gold identity bracelet big enough to scare Puff Daddy. It, too, flashes with diamonds. Labo looks at once daft and sinister. He chain-smokes Marlboro Menthols.

After thousands of dollars of treatment, Zmuda says his friend left Baguio only when his surgeon pronounced him cured. Labo claims he knew he could not help within two days of Kaufman’s arrival. “Mr Kaufman cried and insisted that I keep trying,” says Labo. “After all, he was already here. He had cancer. He was dying. He had nothing to lose.”

Like Hollywood, it seems Baguio might be a place where fact and fiction are blurred for financial gain.

LABO’S OFFICE IS in the basement of the Nagoya Inn, the healer’s surreal, paint-flaking hotel for the sick and wretched that reeks of mould and despair and cockroach killer that doesn’t kill cockroaches.

On a mist-shrouded Baguio hillside, beyond Lourdes Grotto and Holy Ghost Hill, the Nagoya’s garden is slippery with rain and the shit of ducks, chickens, deer and goats that wander listlessly among a frozen freak show of life-sized plaster sculptures — busty mermaids, leaping lions and battling samurai. The Nagoya’s gift shop sells “I Love Jun Labo” T-shirts.

According to the Philippines Medical Association, there are fewer than 50 practising psychic surgeons in the Philippines. The most powerful are in Baguio, where acts of God are common. The town is hit by at least 20 typhoons a year, and accompanying mudslides sweep the corrugated-iron shacks of the poor to the foot of the valley.

In 1990, an earthquake measuring 7.7 on the Richter scale killed 1,600 people in 45 seconds. Life and death revolve around the Immaculate Heart of Mary Cathedral, perched high on a hill in the centre of town like colossal, pink-iced wedding cake.

With his ostentatious lifestyle and cocky manner, Labo is the most controversial of all the healers. Followers call him a misunderstood saint, the Elvis of faith healing, the pope of Baguio. Many more say he is a cynical, dollar-eyed crook with contempt for human suffering.

“I don’t do this for money … I have been chosen by Jesus Christ to heal the people of the world and spread the message of God”

Psychic surgeon Jun Labo

In a nation where the average Catholic family of six barely survives on US$130 a month, he is certainly wealthy. Across the road from the Nagoya, two Mercedes and a 1935 Rolls-Royce sit inside a high-walled compound patrolled by armed guards and snarling dobermans. A Ponderosa-style sign across the tall iron gates declares it to be “Jun Labo’s Residence”. Labo is chauffeured the 100 metres to his office every day in a Space Wagon with tinted windows.

Labo says 80 per cent of the “tens of thousands” of patients he has treated have been cured of afflictions that include cancer, Parkinson’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. He declines to talk about money. “For tax reasons,” he says. “I don’t do this for money. I am being used by the Holy Spirit. It is not my choice. I have been chosen by Jesus Christ to heal the people of the world and spread the message of God.”

Pushed, and he cannot resist bragging. Since the early 1980s, Labo says he has treated more than 100 foreign patients a week at an average rate of US$50 a session. A quick calculation sees his annual income top US$250,000, not including additional revenue from patients paying to stay at the Nagoya.

In 1984, when Kaufman visited Labo, a critical newspaper reporter said the healer was a peso millionaire. According to his biographer, Labo smiled and said, “The report is wrong. He should have said I’m a billionaire.”

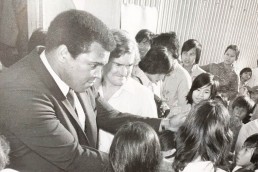

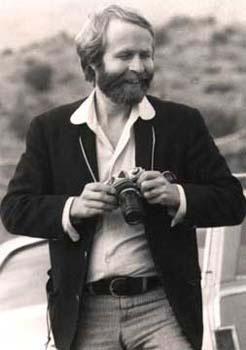

LABO’S FIRST PATIENT of the session arrives. The young, well-dressed Filipina has acute period pain and goitre, a swelling of the neck due to deficiency of iodine in the diet and swelling of the thyroid gland. Labo leads us down a corridor lined with photographs of him healing the multitude. Others show Labo high-kicking in his karate gear and chatting with the late Hollywood actor Burt Lancaster.

We pause for Labo to pray in his spooky chapel, the nerve centre of his Metaphysical Temple of the Universe. The 32 white pews face a metre-high pyramid-like frame that Labo sits under to meditate. The dominant colours are papal white and gold, but the chapel is a confused mish-mash of Catholic, Zen and new-age iconography. To ensure the largest possible market, Labo advertises that he can cure Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, pagans, atheists.

Beyond the chapel, Labo’s surgery is a simple white room dominated by a mournful portrait of Christ and a porcelain statuette of Mary. The patient strips to her underwear and lies on the operating table.

“Watch carefully,” Labo says with a mischievous glint in his eye. What happens next is pure theatre.

LABO SLIPS ON a white surgical gown and rolls up its sleeves. His huge watch and bracelet stay. He closes his eyes to summon up his spirit guide — a native American Indian named Rama, apparently — and he enters a trance.

Labo moves fast and sure. He rests his hands on the woman’s abdomen and a red liquid oozes from his fingertips. Within seconds, he is splashing in a deep crimson pool and a dark stringy discharge appears. He flicks it onto her heaving chest.

Labo’s hands are visible throughout, except when his fingers are sunk deep into the woman’s fleshy midriff. If his performance is sleight of hand, it is extremely well executed.

After rinsing in a bowl of water, Labo keeps his hands in full view and moves to his patient’s neck, where there is no excess flesh in which to hide. Again, blood and matter appear from nowhere. The only logical explanation — divine intervention aside — is that Labo’s assistant, who is constantly replacing soiled towels and shifting fresh ones into position around the patient’s body, is leaving covert props for his master. The entire performance lasts perhaps a minute.

“It was a frame up. They are jealous and they want to destroy me”

Labo, on his recent arrest in Russia for fraudulent practice of medicine

Labo can see I am impressed and he is pleased. But his smile disappears when I bring up Moscow.

According to the Russian and Filipino press reports, Labo was arrested in September last year (1998) for the fraudulent practice of medicine in the Russian capital having treated a nine-year-old boy for a brain tumour.

Labo charged US$1,500 for 10 sessions. When the child’s condition deteriorated, his father went to the police. They raided Labo’s surgery, according to the reports, allegedly to find a stash of cattle blood and entrails in the refrigerator.

“It was a frame up,” Labo says, claiming the boy’s father was in the employ of his political enemies. Labo, who has twice been Baguio’s mayor, also claims the newspapers are being paid to discredit him. “They are jealous and they want to destroy me,” he says.

After six months in Russia, Labo was released in March 1999 thanks to the efforts of Joseph Estrada, the former B-movie actor turned Philippines president, who petitioned Russian Prime Minister Yergeny Primakov for his friend’s release. Estrada also ensured that Labo received VIP treatment while incarcerated in Moscow. “It was like living in a comfortable hotel,” he boasts.

Over the years, Labo has worked hard to maintain good, if morally suspect, political connections. In the early 1980s, he says he rose at 5am each day to board a private plane to Manila, where he would treat the late Philippines dictator Ferdinand Marcos for a kidney ailment. Labo remembers those days fondly. “The president loved me very much,” he says, “because I allowed him to urinate again.”

An appreciative Marcos — who, legend has it, believed the Philippines to be situated under a hole in the universe through which cosmic forces entered — would then rub down a tired Labo with Vick’s Vapour Rub, the healer confides.

Labo also claims he has also treated Libyan strongman Muammar Gadaffi, for heart trouble, as well as the wife of former South Korean president Chun Doo-Hwan, the man responsible for the massacre of 2,000 students protesting his military dictatorship in 1980.

“I will help anybody,” says Labo. “Rich? Poor? It’s all the same to me. I am a simple instrument of the supernatural being we call Jesus Christ.”

THOUGH LABO MIGHT think he is God’s gift, Baguio does not. Rarely leaving his fortified compound, myths have sprung up around the healer like a creepy Filipino Boo Radley. “Labo is number-one quack doctor,” splutters my jeepney driver into town, offering a sarcastic thumbs up and laughing so hard he almost chokes. “He makes good hocus pocus.”

“Nobody in Baguio believes in Jun Labo,” rants Tony, a beefy miner in a “Couples For Christ” T-shirt at the dingy bar of the Swagman Attic Inn, where conversation centres on a recent gunfight between local Baguio gangs keen for the rights to sell fried chicken at the bus station.

A sign above the bar reads, “Alcohol is the greatest enemy of man. But the Bible tells us to love our enemy”. Johnny Cash singing The Beast in Me on the television adds to the frontier atmosphere.

“Only foreigners believe in psychic surgery. It’s voodoo medicine,” adds Tony.

Taxi driver Abe, meanwhile, says he has seen Labo’s men buying cuts of meat in the market that “the poor would not eat”.

Felix, whose business card proclaims him to be a “master butcher”, tells his friends to shut up. “Labo is a very powerful man,” he advises with menace. “Be careful what you say.”

When Labo arrives for dinner with his glamorous, twenty-something Russian girlfriend — a leggy, ice-blond Brigitte Nielson lookalike — on his arm, Felix leaps from his chair to shake Labo’s hand. Abe and Tony sacrifice their San Miguel beers to dart off into the stormy night.

A greasy-haired man in a cheap anorak hugs Labo like a long lost brother. “Thank God that you have come home to us,” he fawns, recalling the healer’s Moscow troubles. The barmaid tells me later that the man is a senior figure at the Bureau of Internal Revenue.

BELIEF IN PSYCHIC surgery is strongest at the extremes of the Philippines’ massive wealth gap. The indigenous poor receive free treatment from the faith healers, who appear to remove tinfoil, coins, stones, bamboo, even dead insects and chickens’ feet from their bodies in line with a belief in witchcraft.

Labo, however, has given up on the destitute. He says they steal watches and wallets from his richer patients, who indulge in psychic surgery simply because they can afford to. But the big money comes from treating foreigners.

The first documented case of psychic surgery was performed in the 1940s, by Eleuterio Terte from Pangasinan province, west of Baguio. It became an international industry in the late 1960s under Tony Agpao, the father of assembly-line psychic surgery whose travel agency flew in charter planes of patients from Europe, North America, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. They slept and dined and spent their money in his wife’s hotel.

In the 1970s, Agpao — who, when he got sick himself, had his appendix removed in a San Francisco hospital — boasted that he was personally responsible for 30 per cent of all the region’s foreign-currency earnings.

Followers of Agpao say the strain of channeling the Holy Spirit resulted in his early death at the age of 42 — in 1982, of a stroke while cruising in his Mercedes. Labo quickly took over the wheel, carving out a healing empire like Baguio had never known.

The son of a psychic dentist (whose magic touch, it was said, could fill cavities, mend rotten teeth and even promote the growth of a new set of gnashers in the elderly), Labo had married a Japanese patient, Yuko Narakawa, in 1980 (they separated in 1998). The glamorous duo became Baguio’s first couple when Labo entered politics in 1984, effortlessly buying the support of the poor with free rice.

Soon Narakawa was also performing psychic surgery under her husband’s guidance, and the couple quickly cornered the lucrative Japanese and Korean markets and played key roles in promotional documentaries on psychic surgery shown across the world. The Marcos connection boosted their money-making potential at home.

Other healers suffered financially from the Labos’ success, including “the Reverend” Placido Palitayan. The Swagman’s barmaid points out one of Palitayan’s patients — a skinny, fifty-something Australian hippy with a shock of curly grey hair and kidney stones — sitting alone in the corner of the restaurant sipping iced water. “No way am I talking to you, man,” he says, more than a little terrified. “You’re giving off an awful lot of negative energy.”

TWO KILOMETRES out of town on the Marcos Highway, Palitayan’s surgery is a small, concrete lock-up opposite Holy Trinity Construction Supplies. He is a stunted, tired-looking 57-year-old in a San Francisco 49ers cap, aviator shades and baggy dad jeans. A patient is waiting, so he yanks open the rusting iron doors to reveal bare walls painted soft pink. Palitayan’s scruffy assistant brushes away the flies and a patient edges onto the blood-stained operating table.

Eyes closed, Palitayan places his right hand an inch above her forehead and concentrates hard for about 20 seconds. What he calls “magnetic healing” complete, he shifts his chipolata fingers to her lower abdomen. Blood appears with an audible “pop” and his hands become flecked with scraps of black tissue. “Infected uterus,” he offers casually, flicking the gunk towards a plastic bucket. He misses and it sticks to the wall with a splat.

In his glory days of the late 1970s and early ’80s, Palitayan says her treated 100 foreigners a day, including tennis player Ivan Lendl for muscle strain and actor Peter Sellers for a heart ailment

Palitayan rinses his hands in a bowl of bloody water and we head next door to his son’s truck-stop cafe. Placido III is preparing pinicpikan, a local dish. The main ingredient is chicken scorched in an open fire. But first, the live foul is tethered and slowly clubbed to death, ensuring that every inch of the chicken’s flesh is saturated with adrenalin-loaded blood when the it finally succumbs to the drawn-out beating and dies. “Compassion is the secret of healing,” says Palitayan. “Not money, big cars and fancy clothes.”

In his glory days of the late 1970s and early ’80s, Palitayan says her treated 100 foreigners a day, including tennis player Ivan Lendl for muscle strain and, in his Manila hotel, actor Peter Sellers for a heart ailment. Sellers died of a heart attack in 1980.

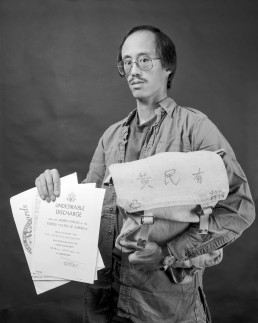

A messy divorce (“she took all my money”) and problems with gambling and booze have succeeded in slashing Palitayan’s business to just five foreigners a month, he says. More than a little bitter, he is frank about the mechanics of the profitable psychic healing industry. Like Labo, Palitayan has had run-ins with the authorities. In 1989, he was arrested in Spokane, Washington, for practising medicine without a licence. After 20 hours of questioning, he says, he was released without charge.

In 1992 he was refused entry to Hong Kong, where he was to hold a week-long healing tour. During his five hours at the airport, he discovered that his sponsor — an American entrepreneur who had promised to split each US$200 fee per patient with the healer — was charging US$400 and ripping him off.

“He was a fool,” Palitayan says. “If he was wise, he would’ve brought patients to me. He would not have advertised. That’s what I need — a partner who is sensible. We could make good money … silently.”

Contrarily, perhaps assuming all publicity is good publicity, Palitayan keeps a cutting of the incident from Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post in his wallet. The headline reads, “Psychic Healer Fails To Soothe Hong Kong Immigration”.

DOWN THE YEARS, most psychic surgeons have been discredited. Back in 1967, Agpao was indicted for fraud in the US, forfeiting a US$25,000 bond when he jumped bail and fled back to the Philippines. In 1986, Manila-based Gary Magno was arrested in Phoenix for the fraudulent practice of medicine after he was found with a plastic pouch of blood and offal in his trouser waistband. He also skipped bail.

These days, Palitayan has a new goal. “To save the world,” he says, with all the excitement of a reluctant retiree anticipating a dotage pottering in his garden. Palitayan will do this through “supernatural consciousness” and his Galacayan Evangelical Mission for World Peace.

His mission statement reads: “There is no exit and no place to hide or escape if nuclear war will broke out, for it is written in the Bible that even though you escape in outerspace, hide in deep bunkers or flee to the bottom of the sea you will still die eventually. This prophecy has been fulfilled thousand years ago, for scientist build mansion in outer space aside from space station. They also establish a city under the bottom of the sea near Japan.”

A Japanese patient told him about the submarine extension of Tokyo. “It’s finished and ready,” Palitayan says, wet lips quivering. “There’s no time to waste.” He adds that another patient, whom he calls a high-ranking US military officer, also shared his secrets about “the button”.

“It’s a big red button,” Palitayan whispers. “And my friend can press it and kill us all. Nobody knows this, not even his own mother.” He winks conspiratorially. “But I know.”

Even so, Palitayan still travels to the US every few months on three-week healing tours to boost his meagre income at home. He treats 20 patients a day, each paying US$75, and avoids the police by performing psychic surgery only “behind closed doors if patients insist”.

Most psychic surgeons in the Philippines, however, prefer their patients to visit them in the Southeast Asian country, where lax laws allow them to practise with impunity. To do this, they utilise the help of overseas agents who promote their work and organise tour groups. These agents normally take the form of new-age stores, alternative healing centres and off-the-wall religious groups.

ROBERT AND MARY Skillman of the Spirit Revisited Seminary in Vallejo, California, first met Labo in March 1990. Since then, the chirpy couple have visited twice a year, introducing 500 paying visitors to the man they call “Godfather”.

“I have so much respect for him,” gushes Mary, whose advertised skills include the “laying on of hands” and teaching Brazilian samba. “Even in the face of so many attacks on his powers, his energy and faith are tremendous.”

She recalls seeing Labo work his magic on a German toddler with deformed legs. “It took Jun Labo just two weeks before she walked for the first time in her life. It was truly a miracle.”

Though Labo was best man at their 1992 wedding in the Philippines, he has never visited the Skillmans in the US. “We want to take him to Disneyland,” says Mary. “He would love it there.”

In the UK, Patrick Hamouy of Alternative Therapies in Gerrards Cross, in Buckinghamshire, uses the Internet to promote “ultimate healing courses” in Baguio under the tutelage of Palitayan’s 59-year-old cousin, “Brother” Laurence Cacteng. According to his website, Hamouy “has studied psychic surgery in depth since May 1997 … His understanding of healing is second to none”.

Priced at £1,950, the two-week courses, according to promotional materials, include therapeutic singing sessions and discussions on the healing powers of angels and archangels, stones, clay, urine and ants.

Hamouy also sponsors Cacteng’s trips to the UK and France. He has introduced more than 100 patients in the past two years, he says, but last year (1998) he had the British health authorities on his back. “I explained, there is no actual surgery in the normal sense,” says Hamouy. “No anaesthesia, no instruments, no cutting. They wrote back and said, ‘Okay, but just make sure his fingernails are clean.'”

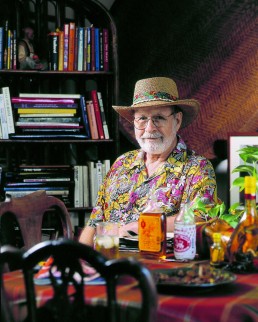

A YOUTHFUL 59-YEAR-old with a pudding-bowl haircut and the pliant face of a chuffed pixie, Cacteng lives in a comfortable detached house in a leafy Baguio suburb. The neighbours’ apple-cheeked kids play ball in the garden.

Sitting at his desk under the healer’s all-important print of Christ, he ushers me in with a wide smile, and he immediately disagrees with Palitayan’s patient with the kidney stones — Cacteng says my vibrations are good and I have a “nice aura”.

Against the wall sits a slate-grey sheet-metal transformer box with two steel plates attached by wires. Cacteng sits me down, places my hands on the plates and cranks up the bakelite dial. As he passes his hand over my ear, a low metallic moan is generated. He pokes a screwdriver into my arms, legs, chest and head. The small bulb in the handle lights up every time. “That’s good,” he says. “No problems.”

Cacteng, who has also visited Switzerland, Germany, South Africa and Australia as a healer, has no fixed prices, preferring patients to “pay from the heart”. Rare Japanese patients are the most generous, he says, splashing out US$50 per treatment four times a day. The French and British might fork out US$300 a week. Poor Filipino’s get away with a chicken in lieu.

As well as psychic surgery, Cacteng offers a wide portfolio of healing techniques. He recalls an Italian patient with breast cancer. “I prayed for her and told her to drink her own urine,” he says. “That fixed her very well.” Cacteng will even offer fatherly advise, as he did with Parisian teenager depressed at being dumped by his girlfriend. “I told the boy, if you kill yourself, she will laugh at you. So don’t kill yourself.”

From his desk drawer he pulls out the secret of “water therapy”. It is a rubber hot-water bottle. Cacteng also shows me a photograph of a patient undergoing water therapy. It shows a grinning Frenchman with a hot-water bottle balanced on his head.

WITH HIS HEAD held high, marching across the lobby of the five-star Makati Shangri-la Hotel in Manila’s high-rise financial district, tall and groomed 38-year-old George Nava True II towers above his compatriots. With his slick-backed quiff, tangerine polo shirt and pressed black slacks, the self-styled “Filipino Quackbuster” has made it his life’s mission to expose “alternative healers, psychics and other quacks” as dangerous charlatans. He grabs a table in the non-smoking section.

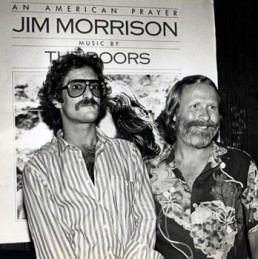

“Blame Burt Lancaster,” Nava True chuckles, explaining that Kaufman’s pilgrimage to Labo was prompted by Psychic Phenomena: Exploring the Unknown, a 90-minute documentary of sorts narrated by the Hollywood star. First broadcast across the US in October 1977 and viewed by 28 million people, the programme has been repeated on TV many times since.

Born of an English father and Filipina mother, Nava True is the grandson of the late Jose Ma Nava, one of the Philippines’ most revered union leaders and editor of La Prensa Libre, a newspaper sympathetic to the plight of the poor. He is also founder of the Health Frontiers Centre for Quackery Control, established in 1983 to expose useless health products and dangerous alternative therapies.

Health Frontiers’ mission statement kicks off with a humorous line — “We should have our minds open, but not so open that our brains fall out” — but Nava True is angry. “These healers can be killers,” he spits. “Sick people give up good treatment that might save their lives to travel halfway across the world to see these quacks. When they get home, it’s too late. They die.”

So why does the government do nothing to protect such patients? Nava True says authorities might be pleased that dying patients visit the Philippines to spend the last of their money and boost the economy. He also suggests the ghost of Marcos, a believer in all things paranormal, still has some influence on policy. “There is no government agency investigating these people,” he says. “And the health authorities have no authority. They can only act if people complain. And how can patients complain when they are dead.”

“In the US, the Federal Trade Commission has practically banned psychic surgery, but the healers get around the law by establishing their own churches and missions”

George Nava True II, the ‘Filipino Quackbuster’

Dr Gil Fernandez, secretary general of the Philippine Medical Association, agrees. “The laws in the Philippines leave us helpless,” he says, speaking by phone. “We believe many psychic surgeons are tricking people, but patients never complain. Either they are ashamed that they have been made fools of, or they have died. Until they do complain, we can do nothing.”

Nava True adds that healers also enjoy plenty of freedom to dupe patients when on tour. “In the US, the Federal Trade Commission has practically banned psychic surgery, but the healers get around the law by establishing their own churches and missions,” he says. “Once they have assumed titles, like brother and reverend, they claim the right of religious freedom and the authorities can’t touch them.”

Surprisingly, Nava True says faith healers are not necessarily wicked people, and that they might actually believe they are providing a genuine service. “They call it ‘true believer syndrome’,” he says. “Some healers have been practising for so long, they really do believe they have the power of God. Perhaps they are the ones that need help. If any of them are interested, I would recommend a good psychiatrist.”

With much work to do, the Quackbuster says goodbye to rush back to his office, leaving behind several press cuttings from Filipino newspapers. The most bizarre is from the tabloid Tempo. Under the headline, “I Am God — Faith Healer Kills Patient, Then Tries To Resurrect Her”, it tells of how in 1992 spiritualist Natividad Sequito murdered a mentally retarded woman while exorcising an evil spirit. She did this by ramming a 30cm length of wood down the 20-year-old’s throat and smashing her over the head with an iron padlock.

Burt Lancaster appears in 'Psychic Phenomena: Exploring the Unknown', the 1977 television special that Nava True says introduced the Philippines' psychic surgeons to a lucrative audience in the West. Video: Patrick Hamouy/YouTube

NAVA TRUE SAYS he detests the new-age travel agents that “make a living from suffering”. He also berates the makers of sensational infotainment TV programmes and writers of books on the paranormal. He says they perpetuate the “fake healing” industry and reap the secondary financial rewards “like scavenging fish around the jaws of man-eating sharks”.

Speaking on the phone from his Los Angeles office, Alan Neuman, of Alan Neuman Productions, maker of the Lancaster-narrated Psychic Phenomena, snaps back. “Labo is 100 per cent genuine,” he says. “I’ve been filming his work for over 20 years. You must understand, the healers are working in another dimension. Just because it is possible to replicate what they are doing with sleight of hand, does not mean that is what they are doing.”

But Nava True’s number-one nemesis is Labo’s biographer, Jaime Licauco, who is also author of the books Understanding the Psychic Powers of Man; The Truth Behind Faith Healing in the Philippines and The Magicians of God. As president of the Inner Mind Development Institute, Licauco — who holds a masters degree in business management — runs workshops in telepathy, telekinesis, spoon bending and what he calls other “advanced mind dynamics”. His two-day Basic Intuition and ESP Development course costs 4,000 pesos (US$100) per person.

An animated, balding 59-year-old wearing a crystal pyramid pendant, Licauco says Filipinos are descendants of Lemuria, or Mu, a mythical civilisation that supposedly existed long before Atlantis somewhere in the Pacific. To avoid hungry dinosaurs, it is said the Lemurians lived underground, growing crops with the aid of crystal-powered light generators.

“As a result,” Licauco writes in The Truth, “[Filipinos’] vibrations are higher and they are able to reach a heightened state of awareness faster and more easily than other people.”

“We had no intention of catching Labo in the act. We only noticed something irregular with the footage back in the studio. We slowed the tape down, but we never reversed it”

Jessica Soho, producer of TV news magazine programme ‘Brigada Siete’

Licauco’s Manila office is decorated with images of Egypt, a country that, he says, he has visited “not only in this lifetime”.

When visiting the UK, he continues, he was cured of a common cold picked up at Stonehenge by veteran British faith healer Stephen Turoff. This was achieved, Licauco insists, by Turoff pushing a five-inch blade up his nose. A framed photograph of the author meeting Pope John Paul II takes pride of place over his busy desk.

“I’m not defending the healers,” says Licauco, who claims Labo removed cysts from his wife’s breast. “I am defending the truth.” But even he confirms that some healers resort to trickery occasionally, when their powers have been weakened by working too hard. They do this, he adds, to ensure their patients are not disappointed.

But the crux of Licauco’s argument is that psychic surgery is a paranormal phenomenon beyond logic and science. When animal blood is discovered at a scene of psychic surgery, he says the healers cannot explain how or why. In short, he argues, the Lord works in mysterious ways. “The blood doesn’t come from the patient’s body. It is materialised by the Holy Spirit,” he says.

Licauco also insists he is not paid by the faith healers, and they do not sponsor his shameless hagiographies. But they do give him “gifts”, he says.

He argues that Nava True and other sceptics manufacture evidence to discredit psychic surgeons. To illustrate his point, he slips a tape of investigative TV news magazine Brigada Siete into the VCR. During the programme, aired while Labo was incarcerated in Moscow, an allegedly cheating Labo is revealed collecting a large chunk of bloody flesh from beneath his operating table.

“There. Can you see?” Licauco cries. “Labo wasn’t bringing his hand towards the patient. He was taking it away. They reversed the film.”

Jessica Soho, Brigada Siete producer — and a Catholic believer in faith healing — denies Licauco’s “ludicrous” accusation. “We had no intention of catching Labo in the act,” she says, laughing, when called. “We only noticed something irregular with the footage back in the studio. We slowed the tape down, but we never reversed it.”

BACK IN BAGUIO, Labo’s guards have put down their guns and are listening to a religious crusade on the radio.

“Are you happy?” the fire-and-brimstone preacher rants through the static. “Then sing praise, sing praise to God Almighty. Are you sick? Then call, call today on the messenger of the Lord. If you believe, if you believe, then you will be cured. And your sins will be forgiven.”

Labo is praying in his chapel. Lost in a trance in front of a weeping bust of Christ, he is performing paranormal house calls, he tells me later, or “distance healing”. He does this by concentrating his “third eye” on the yellowing photographs that decorate the altar — of a sweet, weak old lady balancing on crutches; of an emaciated grey-haired man in a wheelchair; of a sad-eyed teenager with no hair, no eyebrows.

Labo then astrally projects himself, or so he claims, across the oceans to check on their progress.

Finally, sticking to Journalism 101’s tried-and-tested tactic of saving the most insulting question until last, it is suggested to Labo that his big house, his luxury cars and his expensive jewellery may have been purchased by cruelly ripping off desperate people clinging to a last remaining hope of staying alive.

“The people who criticise me don’t believe in God,” he says, casually lighting another Marlboro Menthol with a disposable lighter. On one side, the lighter features a buxom blonde in a bikini. On the other, the words “Jun Labo for Mayor”.

“But they will believe when they are dying. They will pray too. They will come to me.”

With our meeting over, Labo bids a kindly “God bless”and offers a gift, a promotional Japanese videotape entitled Jun Labo — The Only Choice. Watched later, one scene has Labo demonstrating the need for psychic-surgery patients to have an open mind. He does this by twirling a small square of cotton into a thin strand, which he then carefully threads into a middle-aged woman’s left ear. Abracadabra … and he pulls it out of her right ear.

CLEAN-LIVING KAUFMAN also had an unusual way of flossing. After a few days submerged in his depraved comic creation and alter-ego Tony Clifton — a hard-drinking, chain-smoking, whore-hopping Vegas lounge singer — Kaufman would attempt to cleanse his system by swallowing 15 metres of damp cheesecloth. Through a process of controlled peristalsis, he would then pass the fabric through his alimentary canal and out of his backside.

Kaufman’s short life was full of bizarre behaviour and practical jokes. He grappled with women in inter-gender wrestling matches. He took his entire audience at Carnegie Hall out for milk and cookies. He was Elvis’s favourite Elvis impersonator.

Today, die-hard fans hope — even pray — that Kaufman faked his death, that his last-gasp trek to Baguio was just an elaborate twist in a great if morbid hoax. Though a sign at the Nagoya Inn’s exit reads, “Thank You, Come Again”, Labo has not seen Kaufman — or any more of his cash — in 15 years. Not since the comic left the Philippines mountain town thousands of dollars lighter, still dying of lung cancer. ◉

This long-form feature is a little long in the tooth. It was timed for the release of Man on the Moon in 1999, and ran over seven pages in the British edition of GQ, as well as in Max in Spain and Post Magazine in Hong Kong.

SHARE

Remains of the Day

With the toppling of colonial-era statues suddenly de rigueur across the globe, why has Hong Kong kept so many souvenirs of the British empire some 24 years after its return of its sovereignty to China?

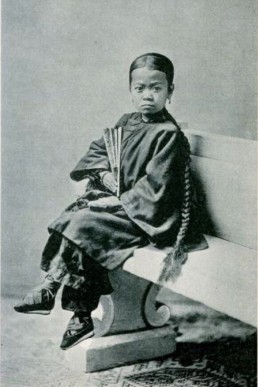

IN 1996, ONE YEAR BEFORE Hong Kong’s return of sovereignty to China, Pun Sing-lui set about the bronze statue of Queen Victoria that sits in the city’s leafy Victoria Park, beside magnificent Victoria Harbour, with a hammer.

As well as caving in the royal nose, he poured red paint over the British monarch whose reign embraced both Opium Wars. Pun’s “art performance”, the recent arrival from mainland China said, was to protest Hong Kong’s “dull, colonial culture”. He demanded “cultural reunification” with the motherland.

Pun’s attack on the statue was almost universally condemned in Hong Kong, with the 26-year-old slammed as nothing more than a publicity-seeking vandal. Four months later — after a nose job requiring a hydraulic jack, acrylic resin and about £12,000 — the screens hiding Queen Vic were removed. She has serenely watched over the public park ever since.

But for how much longer?

IN THE WAKE OF STATUE toppling around the world and noisy calls to “decolonise” public spaces, on top of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) decrying the colonial era as a shameful “century of humiliation”, how can it be that Hong Kong maintains many souvenirs of empire some 24 years after Her Majesty’s Yacht Britannia sailed into the sunset?

After all, in other cases where Blighty bid cheerio to its colonies, new rulers often removed statues to reflect changed political realities without much fuss.

“When the post-colonial administration took over, I think they would have quite liked to have got rid of some things,” says Steven Gallagher, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s faculty of law, with special interest in cultural heritage, adding that Pun’s desecration of Victoria had “focused people’s attention on their heritage” and made them fearful of a threat to their unique cultural identity.

Gallagher recalls recent words of one of his students: “She said, ‘Even though we were young then, we remember what happened with that statue. We just thought, that’s wrong. That’s part of our heritage.’ The colonial identity is part of Hong Kong for Hongkongers … I think if the government did try to remove [statues] now, there would be a reaction.”

Even British drug dealers are immortalised at Jardine Terrace and Matheson Street — named for the Scottish merchants who founded the company Jardine Matheson in the 19th century to traffic in opium, tea and anything else other that would make a buck

And we’re not just talking statues. Many streets, districts and landmarks in what the tourism authority calls “Asia’s World City” celebrate British royalty. Victoria is honoured everywhere, from the harbour to Victoria Peak. Then there’s Upper Albert Road, Princess Margaret Road, Jubilee Street, Queen Elizabeth and Prince of Wales hospitals, Prince Philip Dental Hospital, Queen Elizabeth Stadium, Prince Edward metro station …

Dozens of locations carry the names of former governors, colonial administrators and military officers, including Nathan, Arbuthnot and Stubbs roads, and Wellington, Gough and Elgin streets. Even British drug dealers are immortalised at Jardine Terrace and Matheson Street — named for the Scottish merchants who founded the company Jardine Matheson in the 19th century to traffic in opium, tea and anything else other that would make a buck.

IN THE RUN-UP TO the handover, there was some apprehension in the uber-capitalistic crown colony for what the future might bring, but talk of dread for authoritarian new overlords marching into town was often exaggerated.

China was loosening up, if gradually, its economy kicking into overdrive. The Basic Law, the post-1997 charter hammered out between Britain and China, promised “one country, two systems”, with Hong Kongers governing themselves for 50 years — which they had not once enjoyed in 156 years under the Union Jack.

Since the change of sovereignty, worries about Hong Kong whitewashing its history have, on the whole, proven unfounded, and its Beijing-beholden government has taken a softly-softly approach to heritage.

When attempts have been made to remove British-introduced landmarks, they have largely been to meet infrastructure needs, as with the removal of Queen’s Pier — the original, long gone, named for Victoria — on the harbour front in 2008 to permit land reclamation.

Gallagher says Hong Kong governments — both the colonial and post-colonial administrations — “have never cared very much for what the people think”, tending to act first and deal with any backlash later. Heritage, he says, is one area where they have learned this roughshod approach does not work, with embarrassing U-turns made to quell popular displeasure when authorities have acted without public consultation.

Though the pier was little more than a utilitarian, concrete canopy thrown up in 1954, conservation-minded protests ensued, and the chastened powers that be committed to store the dismantled structure to reassemble it in another location. Gallagher calls the move a “gesture” not requiring significant investment while “appeasing the people”.

And while there is no special designation for Hong Kong’s colonial statues under the law, he says, with only the British-built Cenotaph protected under the Antiquities and Monuments ordinance, they have been left in peace.

Alongside Queen Victoria — unveiled in 1896 to celebrate her 77th birthday — these include bronzes of King George VI, in Hong Kong’s Zoological & Botanical Gardens, and colony financier Sir Thomas Jackson, made chief manager of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, forerunner of HSBC, in 1876.

Jackson’s is the only statue in Statue Square today, in the heart of what once was the city of Victoria and now the business district of Central. The square had been home to many statues, mostly of royalty, but they were removed during occupation in the Second World War, and shipped to Japan to be melted down. Jackson and Victoria were recovered with the end of hostilities and made it home safe and sound.

THERE HAVE BEEN occasional calls for Hong Kong to exorcise the ghosts of its past, most recently in 2018, when businessman Shie Tak-chung — a local delegate to Beijing’s top advisory body, the Chinese Political People’s Consultative Conference — suggested changing street names as part of a patriotic education drive aimed at youth.

Local commentators spluttered in print that Shie’s call to anti-colonial action was just a self-serving publicity stunt — thus giving him publicity — but it was soon forgotten.

Robert Bickers, a professor of history at the University of Bristol specialising in the British Empire and its relationship with China, says there could be many reasons for streets being left alone since 1997, with practicality perhaps trumping ideology. Changing street names, he says, is “really expensive” and disruptive to everyday life. “All the businesses have to change their cards, their stationary,” he says.

Bickers also believes that when such a changeover of sovereignty has come about peacefully, new powers that be have generally been less excited about ripping down symbols of the old regime.

“It’s not as if there has been a bloody insurgency, and the victors arrive and say we’re pulling down him and getting rid of her. It’s not as if the British, for example, are panicking and thinking, ‘We’re withdrawing now, leaving a puppet government behind that we’re pretty certain is going to fall, so let’s take Queen Victoria with us, or at least move her to safety.’”

If such a handover has been “more bureaucratic and negotiated”, he says, ripping down statues is not a top priority for the incomer. “Top priority is showing that you’re a rational, modern government.”

IN TRUTH, SOME symbols of empire have disappeared over the last quarter century, often in acts of self-censorship. In the immediate run-up to the handover, most institutions holding the Royal Charter voluntarily removed the problematic “R word” from their names, including what are now the SPCA, the Hong Kong Golf Club and the Hong Kong Jockey Club. The notable exception was the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club, established in 1893.

The club’s early members were British only, later extending to other Europeans, with Chinese not permitted to join until the 1950s. Women, whom Mao Tse-tung proclaimed in 1968, “hold up half the sky”, could not be full members until 1977. Surely the stain of such discrimination would make breaking with the past a sensible move.

But there is nothing in the Basic Law requiring private organisations to change colonial-era names. The government’s attitude appears to be that it’s none of their business, and for a club’s members to decide. (In fact, back in 1996, a majority of the yacht club’s members did support a motion to remove “Royal”, but this fell short by just two votes of reaching the 75 per cent majority required.)

“Our colonial history is still part of our history. Even if we remove all our colonial-style heritage, we cannot make that part of history disappear forever in Hong Kong”

Roy Ng, of the Hong Kong Conservancy Association, speaking to the BBC in 2015

And soon after the handover, Hong Kong’s bright-red post-boxes were not replaced but simply painted green to match those over the border. Fifty-nine of the old cast-iron boxes, however, were embossed with royal cyphers highlighting the reigns of George V, George VI or Elizabeth II.

In 2015, Hongkong Post deemed them “inappropriate”, promising to cover up the royal cyphers with its modern hummingbird logo. Again, there was a backlash.

“Our colonial history is still part of our history,” Roy Ng of the Hong Kong Conservancy Association complained to the BBC at the time. “Even if we remove all our colonial-style heritage, we cannot make that part of history disappear forever in Hong Kong.”

“How many people noticed [the cyphers] before? But as soon as Hongkong Post said we’re going to do this, people got angry,” says South London-born Gallagher.

To its credit, Hongkong Post listened to the dissenting voices. “There was strong public objection,” Ng says today. “So Hongkong Post said they would collect opinions from stakeholders and heritage groups and make a decision.”

That decision, made in 2018, was to leave the royal cyphers visible, as they remain to this day.

AFTER SHIE’S CALL to change street signs in 2018, Gallagher’s understanding is that the government’s attitude was that “everything’s quiet [in Hong Kong], why have you raised this?” And while Shie was accused by some of brown-nosing CCP bigwigs in Beijing, Gallagher says China has maintained its colonial legacy at times because “they use it as part of their narrative” of the exploitation the country suffered in the past. “There’s much more joined-up thinking about the use of heritage in China,” he says.

That said, recent events in Hong Kong — notably the pro-democracy protests that engulfed the city in 2019, and Beijing’s introduction of the new national security law last year, cracking down on separatism and collusion with foreign governments — make it unlikely we will see much more waving of the Union Jack on Hong Kong streets.

“Things are very different now, so we might see a different attitude [to colonial heritage], but I wonder how important it is for them,” says Gallagher, adding that it remains key to Hong Kong people’s sense of identity, and so removal of statues and changing of street names would perhaps be unwise. “It could be the silly thing that tips them over the edge. I would like to think there’s some common-sense there.”

Ultimately, one wonders what item of Hong Kong’s colonial baggage the next publicity-seeker will attempt to steal away.

Will barristers be stripped of their gowns and horsehair wigs? Will the Noonday Gun — celebrated in Noel Coward’s ditty Mad Dogs and Englishmen, and still fired every day by a staffer from Jardine Matheson — be silenced? Will coins adorned with Elizabeth II’s head, occasionally to be found down the back of Hong Kong sofas, cease to be legal tender?

Or, with Mayor Sadiq Khan’s new Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm set to “review” London’s statues, street names and landmarks, could we soon have a bizarre situation where reminders of empire in the British capital are scrapped or hidden, while the same or similar in a Chinese city 6,000 miles away go unmolested? ◉

These words ran in The Critic magazine in the UK in June 2021.

SHARE

Children of the Damned

Rejected by both the state and their families, the children of serious criminals in China can also be victims of their parents' wrongdoing. The luckiest get a chance to thrive thanks to charitable NGO Morning Tears.

NIU NIU SCURRIES by as fast as her little legs will carry her, and she chews on a strawberry and chuckles as she is chased around the table. The toddler’s guardian, Kou Wei, also giggles as she shoos the three-year-old outside and into the afternoon sunshine. Kou’s job is to care for Niu Niu and youngsters like her — to watch over the sons and daughters of murderers, gangsters, rapists, drug smugglers and other criminals who have been executed or imprisoned for decades in China.

Methodically, one after another, Kou tells the stories of some of the 44 waifs in her care. They are heartbreaking tales of shattered young lives — of violence, trauma and tragedy.

Kou begins with nine-year-old Huan Huan, whose mother killed her father after suffering years of domestic abuse. Huan Huan’s grandfather, in revenge for the death of his son, sold her two sisters.

Xiao Lu, at the age of seven, witnessed her parents beat a man to death. Xiao Yi saw her father slaughter her mother, and Niu Niu is the daughter of a pimp who was jailed when she was just one year old. With the family’s only source of income gone, Niu Niu’s mother abandoned her and her brother.

“We tried to send Niu Niu to kindergarten, but she refused to go, so we keep her here,” says bespectacled Kou, who is the director of the Ai Tong Yuan Coming Home Project, one of only a handful of such specialised childcare facilities in the world’s most populous nation. Despite the harrowing nature of her work, 34-year-old Kou laughs and smiles easily. “The other kids complain because when they are at school, Niu Niu goes through their things and takes whatever she needs.”

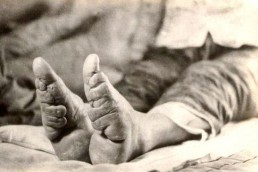

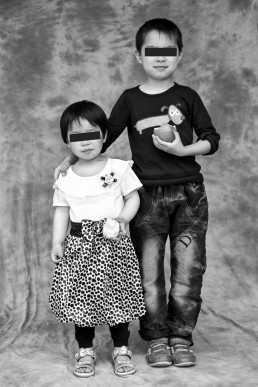

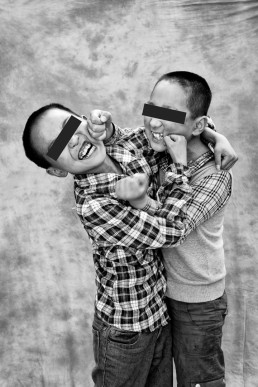

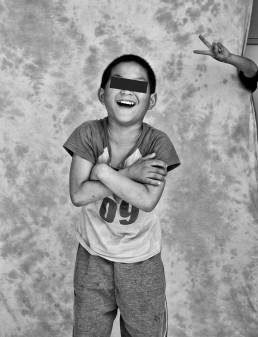

Niu Niu (left), aged three, and Tong Hao (right), nine, are sister and brother. Their father is in prison for 10 years, says Kou Wei of the Ai Tong Yuan Coming Home Project, for forcing ‘many’ women into prostitution. Their mother abandoned them. Photo and opening montage: Palani Mohan

THE AI TONG YUAN facility is located an hour’s drive east of Zhengzhou, capital city of central China’s Henan province. The discreet compound comprises four buildings painted in a peppy apricot-yellow, a basketball court and a playground. The children sheltered here, supervised by adult caregivers, live in five “family units” — essentially self-contained apartments — in the largest of the buildings. No-frills interiors are scuffed and grubby at child height. Cardboard boxes of second-hand toys are anything but overflowing.

“The kids have been through extremely traumatising events,” says Koen Sevenants, Belgium-born founder of Morning Tears, a non-governmental organisation supporting the welfare of such youngsters in China. “In many cases there has been domestic violence. Many have been subject to physical abuse, and sexual abuse in some cases.

“Children who have seen a mother brutally beaten … that can be more traumatising to a child than being beaten themselves. That is a parent they love and they want to protect that parent, but at that age they cannot.”

The children at Ai Tong Yuan clearly adore “Uncle Koen” and the older lads leap onto his broad shoulders, pleading noisily with Sevenants to arm-wrestle or play rock-paper-scissors. In his work uniform of scruffy jeans and baggy T-shirt, and with his mop of unruly blond hair and ginger beard, the 1.8-metre and burly European must appear, in their youthful eyes, like a bear — a teddy bear of seemingly inexhaustible playfulness and patience. Sevenants, 41, holds a doctorate in psychology. He has worked for aid groups all of his adult life.

“These are the children nobody wants,” he says, explaining that the offspring of convicts — still having grandparents, perhaps uncles and aunties — are not recognised as orphans by the Chinese state. “Very often relatives don’t want them. In cases of murder resulting from domestic abuse, the father’s family don’t want them because they see the mother in the children. The mother’s family see the father.”

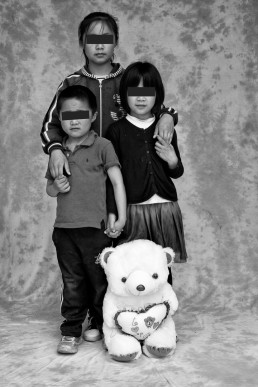

Pan Pan (left), aged 6, Xiao Lu (centre), 13, and Lu Lu (right), 8, are siblings. Their father was one of China’s army of migrant workers, leaving the countryside to make a living in the city.

With her husband away, their mother suffered the repeated attentions of the son of a local village chief. She fought back, but the man persisted, even continuing his harassment once her husband had returned. A fight between the three resulted in the man being beaten to death. The couple received life sentences. Photo: Palani Mohan

Huan Huan is nine years old, comes from a rural family and has two younger sisters (China’s one-child policy is not enforced as rigorously in the countryside, especially when offspring are girls). Their father was violent towards their mother, who — with the help of her own father — one day fought back. The brawl resulted in the husband’s death. Huan Huan’s mother was sentenced to life in prison, her maternal grandfather to 10 years.

Huan Huan’s paternal grandparents held a grudge and yet took custody of the three girls. Two years ago, they sold Huan Huan’s sisters, then aged five and three. ‘The grandparents will not tell us, or even the police, where they are,’ says Kou. ‘They want to punish Huan Huan’s mother.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

LESS THAN THREE hours west of Zhengzhou by air-conditioned express train, Xian, the provincial capital of Shaanxi, is one of China’s most ancient cities and home to the Terracotta Warriors. The Morning Tears-supported Sanyuan Children’s Village is a 90-minute drive to the north.

Unlike tranquil Ai Tong Yuan, the Sanyuan sanctuary, home to 47 children, rests beside a busy road. Articulated trucks roar by at speed, thrashing up dust and blasting their horns, and the main building is an austere construction that has been pleasingly overwhelmed by bottle-green ivy on the side of its shaded playground.

The playground has a climbing frame, a bench swing and canary-yellow exercise machines. While lunch is being prepared, children scrub their faces and hands from stainless-steel kitchen bowls at the ping-pong table.

Pictures torn from glossy magazines, of boy bands and coquettish movie starlets, add splashes of personality to the paint-flaking dormitories in which the children sleep

Sanyuan director Yang Biao, 50, is welcoming but cautious of strangers. When asked for details of children in his care, he initially and protectively sidesteps the request. Yang relents over two days, conceding that he can be wary of outsiders’ motives.

Like Kou before him, Yang produces brown-paper A4 envelopes containing individual human stories. Yang tells of one crime-orphaned youngster who arrived at Sanyuan when she was 13. Her family had lived in a mountainous area and the child’s father had been a roaming carpenter who became romantically involved with a woman in another village.

The lovers decided to kill the carpenter’s wife. Poison failed but a nail hammered into the woman’s head, Yang says, proved effective. The carpenter was executed.

“We have a boy, he is 13 now, who came to live with us last year,” says Yang. “His mother had been a teacher in Xian city. She and members of her family beat his father to death after a quarrel over gambling, and [the father’s] drug taking and drug dealing. The mother just couldn’t take it. She was jailed for 20 years.”

A portrait of Mao Zedong — the same airbrushed image that looks out across Tiananmen Square in the capital Beijing — is fastened high on the wall at the front of the Sanyuan operation’s basic classroom. Pictures torn from glossy magazines, of boy bands and coquettish movie starlets, add splashes of personality to the paint-flaking dormitories in which the children sleep, perhaps hugging the threadbare stuffed toys that are now scattered across their beds.

Occasionally, Yang reveals, children arrive at Sanyuan as babies. One child, now aged four, was newly born. “When her parents were arrested for drug dealing, her mother was ready to give birth,” Yang says. “The father was locked up, but the woman was taken to a hospital. Within a week of the baby’s delivery, the mother fled.”

Yang says the infant had not been given a name, and light drizzle was falling when police officers brought her to Sanyuan, where staff christened her. Xiao Yu means “Little Rain”.

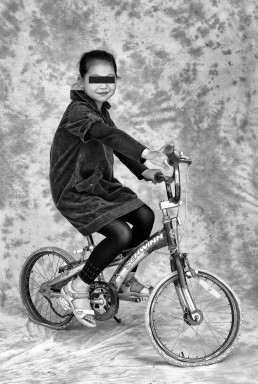

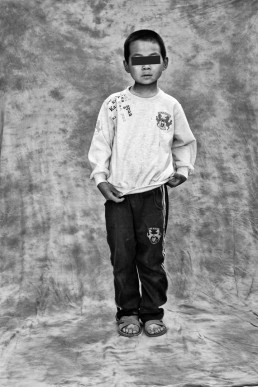

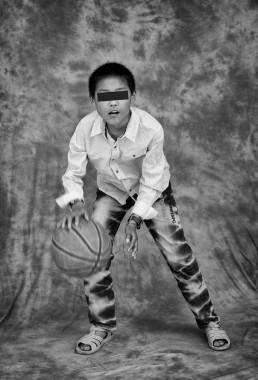

Yu Kun, 14, comes from a poor family and, according to Yang Biao, director of the Sanyuan Children’s Village, his early years were plagued by domestic conflict. When Yu Kun was three years old, his father beat him so badly that his mother killed her husband with rat poison, cutting his throat to ensure he was dead. Having pleaded mitigating circumstances, Yu Kun’s mother has been imprisoned for life. The boy has been cared for since 2004. Photo: Palani Mohan

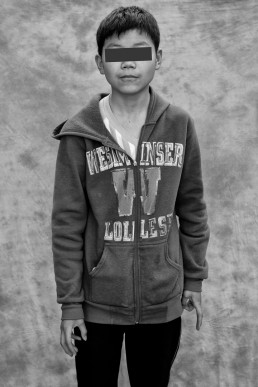

Xiao Ze (left), aged 10, and Xiao Wei (right), 12, are brothers. Following a disagreement, their father shot and killed a local villager with his hunting rifle in 1995. The father was captured and executed in 2005 after 10 years on the run.

The boys lived with their grandfather after their father fled and were taken in at Sanyuan in 2009, when their ageing guardian could no longer cope. One hour after this photo was taken, the boys’ grandfather took them home for the May Day holidays. Photo: Palani Mohan

THE ORIGINS OF Morning Tears can be traced back to 1996, when four Chinese judges — obliged by law to hand out death sentences and lengthy jail terms — recognised the plight of the children left behind and decided to act, financing from their own pockets three facilities in and around Xian.

The judges’ cash drained away quickly, however. Their first facility closed after just two years. Three years in, and the second space wound up. The third was about to expire when Sevenants, based in Beijing at that time and employed by Handicap International as country manager for China and North Korea, discovered it. “[A colleague and I] started out as volunteers,” Sevenants says, shrugging at the memory of their naivety. “And then everything spun totally out of control.

“One day, you realise that you are thinking a lot about the children. You can’t sleep when they have problems. Anyway, after a while, we said, ‘This has gone much too far.’ We decided to source the money [required] to keep the kids going for two years and hand everything over to local people. For us, it would end, we could get on with our lives. And that’s what we did. And that went well for … about two weeks. We couldn’t walk away, we just couldn’t, and so we decided to do things properly.”

Today, Morning Tears has 100 or so staff in China, with about 40 of those being volunteers. It shores up four core projects: Ai Tong Yuan, Sanyuan and one other facility near Xian, and another close to Beijing. There are smaller operations in the cities of Chengdu and Wuhan. Morning Tears supports — at various levels, from full-care to individual assistance with schooling — about 580 children. More than 1,000 youngsters have benefitted since Morning Tears was founded. Its earliest wards are now adults.

Those numbers are just drops in an ocean of juvenile despair, however. According to the Chinese Ministry of Justice, there are 600,000 children of convicts in the country. Many are without guardians and the youngsters beg, hustle and thieve on the streets to survive. Childhood trauma manifests itself in self-harm, anti-social behaviour and nightmares, says Sevenants, and many young sufferers will also become convicts in a pan-generational cycle of misery.

The number of people executed each year in China, meanwhile, is a state secret. International watchdogs claim the country kills thousands of its citizens annually — more than the rest of the planet combined (the United States put 46 people to death in 2010). Capital punishment is employed for more than 50 crimes in China, ranging from tax evasion to murder (mitigating circumstances are considered in individual cases). Executions have traditionally been carried out by a single gunshot to the head. Lethal injection has come to the fore in the last decade.

Nine-year-old Ming Ming arrived at the Ai Tong Yuan facility at the age of six. Her parents are in prison for 11 years for stealing cable to sell as scrap. ‘She finds it difficult to visit her parents [who are in different prisons] because her father always complains about her mother, and her mother complains about her father,’ says Kou. ‘The parents can’t see each other, so they argue through the child. Ming Ming doesn’t like prison visits.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

Liu Fei, aged eight, arrived at Sanyuan in March. His parents had been jailed for 20 years for being members of an organised gang of car thieves. The gang had been operating for at least five years, and for much of that time — since Liu Fei was three — the boy had been kept with the family’s sheep. ‘He lived with the sheep, he ate with the sheep,’ says Yang. ‘When he came here he could not walk properly. He has problems communicating.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

BACK AT THE AI Tong Yuan Coming Home Project, the children have finished a simple lunch of noodle soup and steamed buns. Some take naps. Some bend over exercise books with colouring pencils, sketching houses, apple trees and rainbows. Huan Huan watches television and Sevenants is reading a story to cross-legged children in one of the dormitories. Niu Niu plays with a discarded mineral-water bottle.

Inside the two-metre-high wrought-iron fence and wall that surround the compound, the young residents of the project are safe amongst their own. Life can be less secure beyond the perimeter, with the children of convicts spurned for bringing bad luck and for carrying criminal tendencies in their DNA.

Kou cites the case of Meng Meng, who is now 12. Meng Meng’s father was incarcerated when she was four, and her mother deserted her. Meng Meng then lived with her grandfather, but his neighbours refused to accept the girl into their community. Through those neighbours, Meng Meng discovered that her father was a rapist. “She refuses to visit her father in prison,” says Kou.

Kou tells of Xiao Yan, another 12-year-old, who arrived when he was eight. The boy’s father is in prison for life for theft. Xiao Yan’s mother rejected him and he was sent to live with his uncle. Neighbours in his uncle’s village shunned Xiao Yan as the offspring of a felon. “He became a troublemaker,” Kou says. “[Xiao Yan] told me that he didn’t want to be that way, but he couldn’t make people understand that he was not a bad kid. In his mind, he was left by his father, by his mother, then by his uncle. Nobody wanted him.”

“Girls, maybe 14 or 15 years old, have been taken away because relatives want to marry them off. I worry when a girl of that age is taken from us”

Morning Tears founder Koen Sevenants

Sevenants believes it is preferable for children to be cared for by family members, and there have been instances of children being taken away after years in Morning Tears’ care by relatives. Blood ties, however, can prove less than ideal.

“A child might go to an aunt or a grandparent, but their education could stop,” Sevenants says. “They will have to earn their keep, they might be beaten and then, after a time, they can be cast aside and traumatised for a second time. We’ve had kids arrive back here with [bruises] and cuts. They are underweight, they haven’t been to school for years …”

There are many reasons, Sevenants believes, why relatives might collect children. “We had one case of pure child torture — a brother and a sister, 13 and 10 years old,” Sevenants says. “Their parents had been executed for drug smuggling and an uncle was convinced that money had been hidden away. The uncle tied [the children] to chairs and beat them for information. When he failed to find money, he just returned them to us.”

Also troubling is the fact then when a young woman marries in rural China, tradition dictates that the groom’s family must pay the bride’s kin. “Girls, maybe 14 or 15 years old, have been taken away because relatives want to marry them off,” says Sevenants. “I worry when a girl of that age is taken from us.”

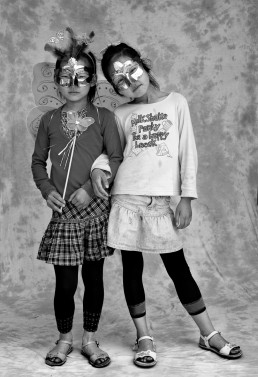

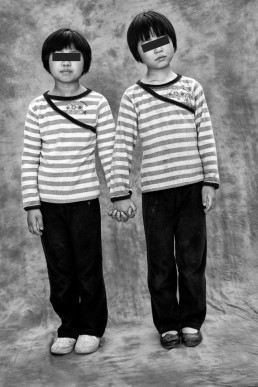

The father of Yi Li (left), aged nine, is in prison for stealing. Her mother divorced him, remarried and left. Yi Li has been cared for at Ai Tong Yuan for three years. ‘Yi Li is an angel,’ says Kou. ‘She’s patient, she helps the caregivers and she’s very smart, top of her class … everyone loves her.’

The parents of Dan Dan (right), also nine years old, are in jail for poisoning a man who regularly made unwelcome advances towards her mother. They were sentenced to death for murder with a two-year reprieve, meaning their sentences could be commuted to life imprisonment. ‘Dan Dan is a very pretty girl and she knows it,’ says Kou. ‘She’s not a great student. Every day her caregivers complain because she will spend an hour or more on her hair.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

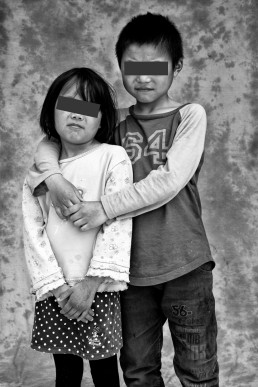

Siblings Xiao Wan (left) and Xiao Yi (right) are aged nine and six respectively. Their father received the death sentence for murdering their mother. His sentence has been deferred for behaviour appraisal and may be commuted to life. ‘They have visited their father in prison, but they think he is the devil,’ says Kou. ‘They have a lot of nightmares.’

Kou has found the case difficult to handle. ‘Xiao Wan told me that his father had often been abusive to his mother and there was always violence at home,’ she says. Photo: Palani Mohan

OCCASIONALLY, EMOTIONALLY damaged children will reject protection, as was the case with Xiao Sheng, whose mother stabbed and killed his father when the boy was just five. She was executed and Xiao Sheng was cared for until he was 14. “He was eaten up by anger,” says Sevenants. “He would not calm down. He was convinced his mother had been innocent. He wanted revenge and he left us at too young an age.” With nowhere else to turn, Xiao Sheng took a job in a coalmine. He died in a mining accident at the age of 15.

In the same way that communities have scorned individual children, Morning Tears projects have also come under attack. “In 2000 we had a security problem and had to move one of our facilities,” Sevenants says. “Our children were being beaten.”

A public-relations exercise was put into place, to reposition the home as a community project where all would be welcome. The walls would come down. “We wanted to hold film showings in the evenings, invite local children to join us,” says Sevenants. “We had to give it up, build a wall again, lock the gates — not to keep our kids in but to keep local people out; to stop them from stealing things and treating our children badly.”

And the psychologically exhausting headaches do not stop there, with the pain of the children transferring to their adult protectors. Kou, especially, has confronted demons.

Kou’s mother killed her violent father in 1996, while she was studying English at university in Xian. “I am one of [these children]. I feel how they feel, and I can show them something, but I’m not always sure what it is,” Kou says. “They feel safe with me. It’s difficult to put into the words, but I strongly believe that the children understand me.”

Jia Yu is 11 years old. His father is incarcerated for stealing and his mother abandoned the boy. ‘Many of these families are very poor and depend totally on the father,’ says Kou. ‘When a father goes to prison, there is no income at all, so mothers often leave and start again.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

Xiao Yan, 12, arrived at Ai Tong Yuan when he was eight. His father is in prison for life for robbery. His mother abandoned him. ‘He was a very troubled boy [on arrival], having fights with caregivers and other kids,’ says Kou. ‘Now he’s a sweetheart.’

Kou says Xiao Yan suffers from abandonment issues. ‘We were holding a drawing exercise, helping the kids to express their feelings, and he drew a black heart,’ she says. ‘I asked him why the dark colour and he said, ‘This is the feeling I have for my mother.’’ Photo: Palani Mohan

SEVENANTS HAS ALSO struggled with emotional fall-out. He no longer attends when children visit parents in prison. “There’s a lot of pain involved and it gets into your system,” the Belgian says through a sigh. “They say things become easier with time, but I find it more difficult now than in the past. I try to keep distance, to limit involvement. I had to seek personal assistance at one point, to help me cope with things, to digest things.”

Caregiver Hong Li, 30, has a five-year-old son of her own. “The first year, when new children arrived and I heard their stories, I would find it so heartbreaking,” Hong says. “I couldn’t control myself. I cried a lot.”

These days, Sevenants focuses on the fundraising side of Morning Tears, which now has presence in the United States, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, France, Italy, Germany and Spain, as well as mainland China and Cambodia. Basic care for each Chinese child costs around Rmb350 (then about US$6) a month.

“That not only includes food, clothes, housing, but also a meaningful life with school and hobbies, with psychological and personality development assistance,” he says. “But prices are going up and inflation is a problem. Last year the price of pork [in China] rose fourfold.”

Companies and corporations … when they hear ‘death penalty’ and ‘criminals’, they worry that we might be a human-rights organisation that opposes the Chinese government

Sevenants on drumming up funding

The global economic crisis has curtailed donations, but Sevenants has a more fear-led than finance-driven challenge to overcome. “People are afraid by what we do,” he says. “Companies and corporations, of course, donate money to community causes. When they hear ‘death penalty’ and ‘criminals’, they worry that we might be a human-rights organisation that opposes the Chinese government. They don’t want to be associated with us. They are scared of us.”

That ill-informed attitude is frustrating, especially considering that Morning Tears and the Chinese authorities collaborate. The Ai Tong Yuan Coming Home Project is jointly operated by Morning Tears and the state-run Zhengzhou Children Protection Centre. Sevenants is a consultant to the Chinese government in the upgrade of child-protection laws and procedures. Morning Tears is legally registered as an NGO in China, enabling it to issue state-approved receipts so that donations are tax deductible.

In 2010, in fact, China’s central government rewarded Morning Tears with its ultimate stamp of approval, presenting the NGO with the China Charity Award — the nation’s most prestigious honour in that field. “Actually, I think they may have given the award to help us,” says Sevenants. “To show that it’s okay to support what we do.”

Coming from a poor rural family, Li Wei (left), aged eight, has been cared for at Sanyuan for two years. Her father was a migrant worker making a meagre living as a labourer in Xian. When his employer held back his wages, Li Wei’s father attacked the man and received seven years for assault. Her mother suffers from schizophrenia.

The mother of Wang Yi (right), also eight, suffers mental-health problems and left the family in 2006. Her father died in 2009 of pneumonia. She has been cared for at Sanyuan since 2010. Photo: Palani Mohan

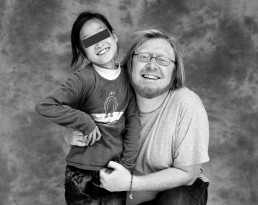

‘In the past, 90 per cent of the children we supported were from rural, financially disadvantaged backgrounds,’ says Koen Sevenants, the general director of Morning Tears. ‘That has changed and there is more diversity these days. Urban drugs have played a large part, and we are increasingly taking in kids originally from quite well-off families.’ Photo: Palani Mohan

WITH THE SUN SETTING behind a neighboruing factory, the oppressive heat of the day subsides and the children of the Ai Tong Yuan Coming Home Project have finished classes. Dan Dan, aged nine, claps and slaps and grins through a lively session of patter-cake with Kou. Eight-year-old Lu Lu slaloms by on the single skateboard shared by all of the 44 children. Dan Dan and Lu Lu are daughters of convicted murderers.

Two studious children attack their homework, standing at the outdoor ping-pong table. Faded sweatshirts and battered canvas sneakers drip-dry on a railing and weary caregivers, who have been digging an allotment and planting peanuts, wipe sweat from sun-darkened brows. If the peanuts flourish, sweet potatoes and melons, perhaps even Niu Niu’s favourite strawberries, might follow.

Despite the myriad problems they confront every day, Kou, Sevenants and their colleagues agree: the rewards of their cause outweigh the heartache. “Relearning how to play, to trust and make attachments, is very important,” Sevenants says. “We give children a safe environment in which to do that. It’s a glorious moment, it feels fantastic, when you see a child, who was terribly traumatised on arrival, start to play again.”

Caregiver Hong, who has been with the facility of three years, concurs. “I’ve had many chances to take jobs with better salaries, better conditions, but then I start to feel upset,” Hong says. “I end up saying no. The children and I have become so close.”

Hong’s friend and colleague Dandan, 22, has also been a caregiver for three years. “I’ve seen many positive changes,” she says. “Little Fanfan [believed to be aged seven] arrived two years ago. She wouldn’t speak — not a single word — for two or three months. She would cry all the time. She would kick and hit out at anyone who came close. Now she’s happy and polite. She loves to share time with the other children.”

For Kou, the experience has been especially life-affirming, assisting her in dealing with her own distressing past. “The way the kids express their inner anger … I can see that, well, maybe that is not always the right way,” Kou says. “Sometimes [in the past], when I have reacted to things, I have not always been able to control myself, to see the right way and the wrong way. The children have taught me a lot.”

AN HOUR PASSES and stars are appearing in the clear evening sky. Caregivers are rounding up the children to clean their teeth before bed.

Niu Niu drops the day’s last strawberry into the dirt and one of the project’s two pet dogs — strays taken in from the neighbourhood — sniffs at the discarded fruit. Niu Niu fashions her chubby fingers into a V and raises them towards the photographer’s camera. She looks directly into the lens, her dark eyes sparkle and she smiles an innocent’s smile. ◉

Children’s names have been changed. Their stories and censored portraits have been approved for publication by their guardians at the Ai Tong Yuan Coming Home Project and Sanyuan Children’s Village.

This long-form feature ran in Hong Kong's Post Magazine and now-defunct Australian website The Global Mail in early 2013. They are no longer online. Morning Tears' Facebook page is here.

SHARE

Soldiers Waging Peace

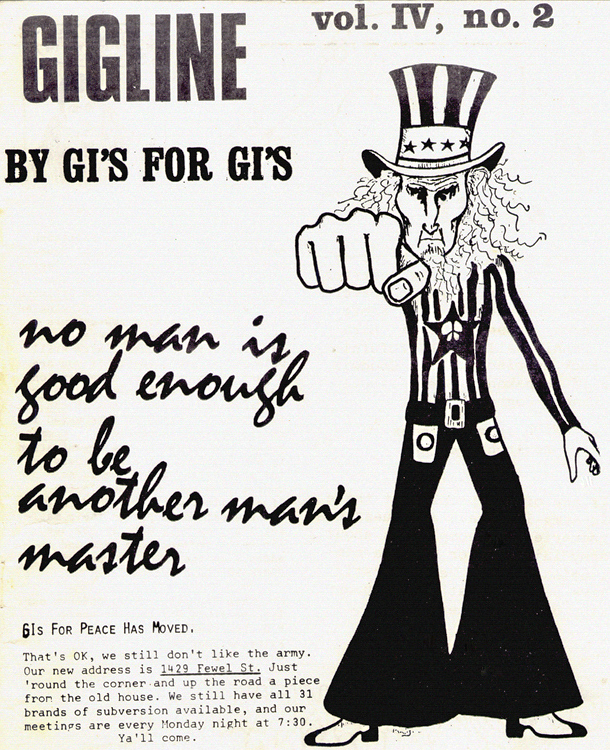

A veteran civil rights activist says GIs were on the frontline of the anti-Vietnam-war movement, organising protests, publishing underground newspapers and serving jail time to end the fighting in Southeast Asia.

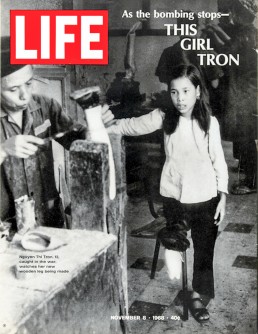

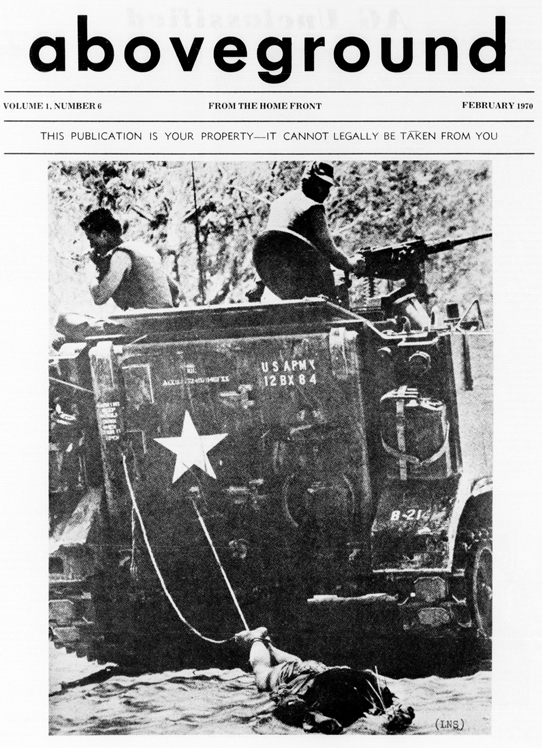

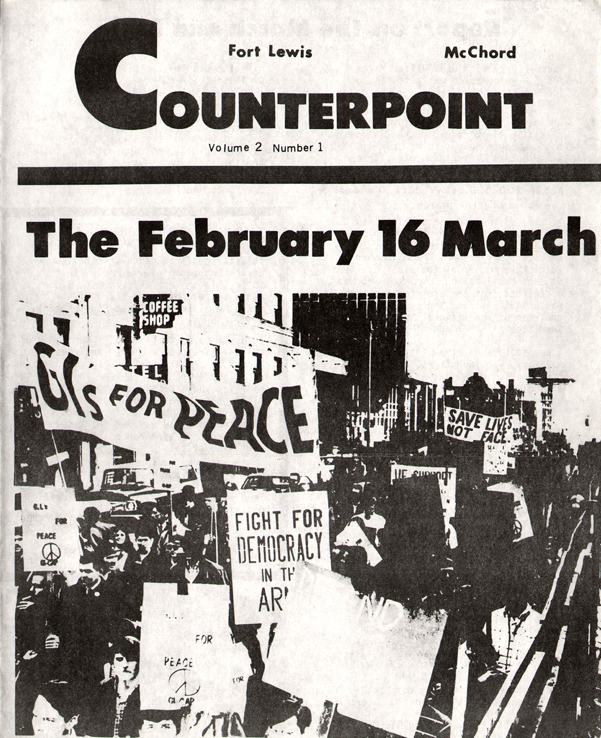

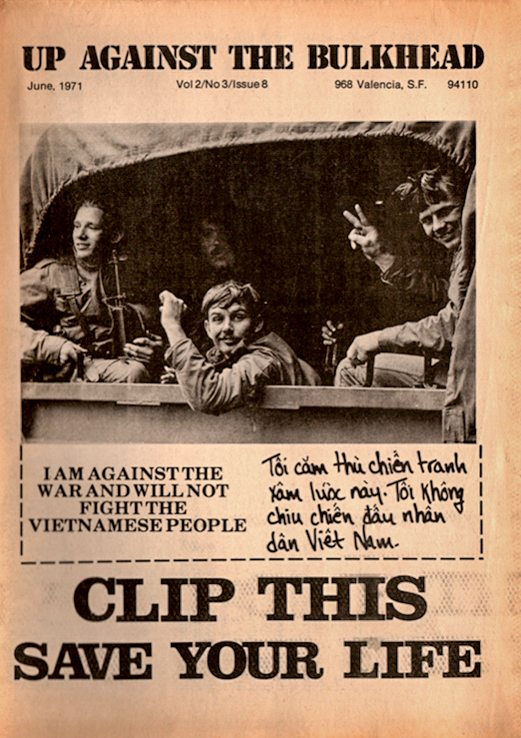

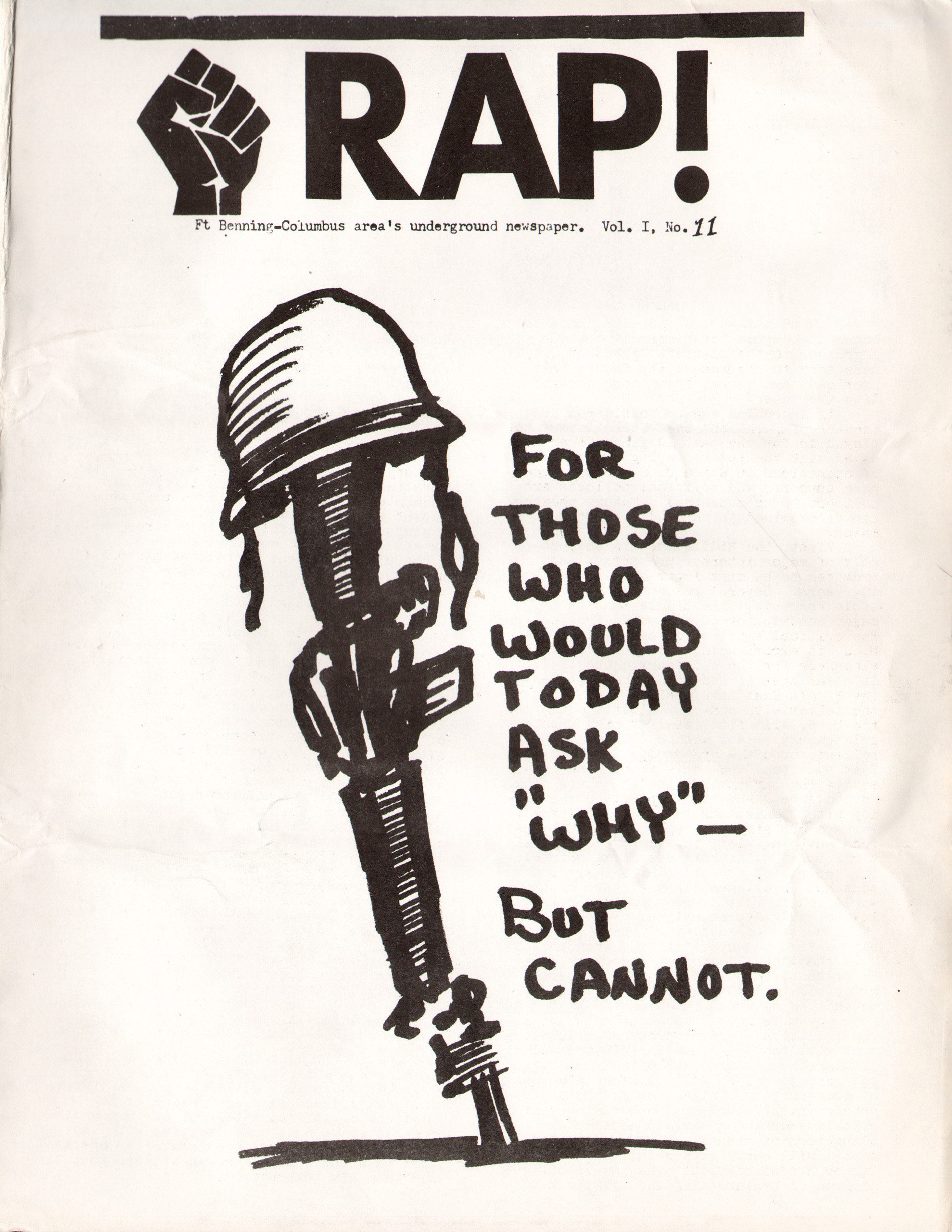

THE STEREOTYPICAL IMAGE of the Vietnam war veteran, returning to the United States after an arduous tour of duty, only to be spat upon and cursed as a murderer by sneering, long-haired peace protestors, is seared into the American psyche like a scar from a white-hot burst of napalm. The accepted belief is that weary veterans trudged home to be condemned, cold-shouldered, even physically assaulted — simply for doing their duty.